Dead mine walking

Agencies empowered to protect the state’s people and natural resources have instead flouted environmental laws to aid foreign mining corporations

This view of the northwest corner of the NorthMet holding dam shows how wet this part of the state is. If the tailings dam were to fail this would be the first area to be inundated with sulfuric mining waste. The pollution would then flow north into the Embarrass River, and from there into the St Louis River and finally on to Lake Superior in Duluth. Photos by Rob Levine.

Foreign corporations are vying to mine copper and nickel on the cheap in northeastern Minnesota in ways that could contaminate the area for millennia, and the state’s Department of Natural Resources and Pollution Control Agency, charged with protecting our waters, have been helping them with permits deemed illegal by the courts.

A 2021 decision by the Minnesota Supreme Court has given the Minnesota Department of Natural Resources (DNR) a perfect opportunity to drive a stake in the most procedurally advanced – and potentially dangerous – proposed sulfide mine in the state. Will it finally take an off ramp?

The northeastern Minnesota project, called NorthMet and owned jointly by Swiss and Canadian companies, would be the first so-called sulfide mine in the state. Sulfide mining is more complicated and produces more toxic waste than Minnesota’s traditional iron mining. Where iron mining waste is stored in tailings basins actually meant to leak a bit, sulfide mining waste storage should be water tight, because the tailings are so toxic.

The stakes could hardly be higher. A catastrophic tailings dam failure could inundate the environmentally sensitive area between Hoyt Lakes and Babbitt with two billion gallons of sulfuric mine waste, which would inevitably infiltrate into thousands of square miles of the St. Louis River watershed, spreading like blood through capillaries. It has happened in other places like Mount Polley, Canada (2014), Mariana, Brazil (2015), and Brumadinho, Brazil (2019), surprising engineers and geologists.

The effects would be devastating to the area as a wave of toxic liquid pollution filled with sulfur, mercury, arsenic, copper, nickel, manganese and other heavy metals flowed north to the scenic Embarrass River or south to the Partridge River, and from those two places west to the St. Louis River, which drains most of northeastern Minnesota, and on to Lake Superior at Duluth. It would destroy a portion of the state’s wild rice fields, kill millions of fish, disable farms, foul city water supplies, and render some of the wildest and most scenic parts of the state unfit for human or animal life.

With those kinds of potential consequences, you might think state and federal agencies charged with protecting our natural resources would be careful with their approvals, and that the profits would flow back to the state, or at least to companies based here.

Unfortunately, as the project has unfolded under the control of two Democratic governors in the past 15 years, none of that is true.

This is the story of that proposed copper-nickel mine, and how at stage after stage the agencies empowered to protect the state’s people and natural resources have instead flouted environmental laws to aid foreign mining corporations in ways that could have catastrophic results.

Ownership of the mine and its mineral rights have passed through more hands than a bong in a Harold & Kumar movie. Currently the project is owned by a company called NewRange Copper Nickel, an equal partnership of PolyMet, now 100% owned by Swiss mining giant Glencore, and Teck Resources of Canada. Courts still refer to the project as either NorthMet or PolyMet.

First proposed in 2005, the mine would be built by bulldozing former National Forest Service wetlands and digging pits as deep as 700 feet. The ore at the bottom is actually low-grade, encased in hard rock, and 99.7% waste. PolyMet would then process the ore at a converted iron mining plant six miles away.

And although there are problems with other major aspects of the planned mine, the use and expansion of a 3,000-acre tailings waste storage facility (called a tailings “basin” even though it is a mound of tailings the consistency of sand or finer) left over from previous iron mining, has been the center of controversy. In the PolyMet plan, sulfide processing tailings would be added to the iron tailings and the basin would be repurposed for sulfide mining waste.

Before the DNR could grant PolyMet a permit to mine, it first had to issue a valid Environmental Impact Statement that passed muster with the federal Environmental Protection Agency (EPA). The first attempt in 2009, called a Draft Environmental Impact Statement, earned the EPA’s worst rating, called an EU-3:

“EPA has rated the DEIS as Environmentally Unsatisfactory - Inadequate ... our review has identified adverse environmental impacts that are of sufficient magnitude that EPA believes the proposed action must not proceed as proposed.”

The EPA identified the same basic issues with the NorthMet project that were cited by the Minnesota Supreme Court 11 years later to strike down the project’s permit to mine, including water contacting “acid-generating waste rock.”

The EPA also wrote that the DNR hadn’t done detailed geological modeling, and that “... the analyses of the hydrogeological profiles at both the mine and processing sites are inadequate to determine the full extent of impacts.”

Playing politics

Those early warning signs weren’t enough to ward off Minnesota’s Democrats, who looked at the close balance between themselves and Republicans in 2010, and privately decided that certain sulfide mines should go forward not on the basis of science and economics, but politics.

Paula Maccabee, lead counsel for WaterLegacy, an environmental nonprofit that has been fighting NorthMet and other sulfide mines for almost two decades, says she was told at a DFL fundraiser early in her work that, “PolyMet is a done deal. They said that not only would I fail to stop the project, but that it was bad politics to try.”

Tom Landwehr, who was appointed commissioner of the DNR by then-newly elected DFL Governor Mark Dayton, told the Worthington Daily Globe in 2011 that he understood “...the importance of expanding mining in northeastern Minnesota and other business-oriented changes...” and that “...It is just going to be critical that we find ways to make mining acceptable...”

Landwehr, who we have been unable to find for comment, averred that he planned “...to do what he [could] to halve the time it takes the DNR to issue permits and to take other actions.”

No matter the intent, the DNR had trouble keeping the PolyMet show on the road. A 2012 leaked memo from a DNR employee in the dam safety unit warned that the proposed method for treating the tailings basin after mine closure "... significantly increases the potential for a dam failure..." and suggested that "... the tailings dams must function properly for an extended period of time – we’ve heard on the order of 900 years.”

All of this made Dayton, who had won the governorship by only 9,000 votes, so frustrated that in 2013 he said he "would like to abolish the federal Environmental Protection Agency" for delaying the project. His commissioner and assistant commissioner for the Minnesota Pollution Control Agency would later come under fire for hiding negative EPA comments on the NorthMet water pollution permit, which would also be overturned.

It would be another three years before the DNR’s Environmental Impact Statement for the NorthMet project was deemed adequate. Then, finally in January 2018, the DNR issued its draft permit to mine for the NorthMet project. A month later, Maccabee and her team from WaterLegacy filed a petition with the agency for what›s called a contested case hearing, challenging a host of facts put forward by the DNR in the draft permit to mine.

It’s eerie looking back at how much WaterLegacy’s request for a contested case hearing in February 2018 echoed the concerns of the EPA in 2010, the DNR’s own consultants in 2012 and the Minnesota Supreme Court in 2021.

Maccabee wrote that PolyMet’s plan for closure didn’t meet Minnesota’s mining waste rules which preclude “substantially all water” from “moving through or over [reactive] mine waste,” and did not meet the legal requirement that within three years after the start of closure, “the permittee shall provide for drainage of the basins and reintegrate the area into the natural watershed.”

The DNR rejected those concerns when it approved the permit to mine later that year. But the issues raised haunt the project to this day.

PolyMet’s original sin

Planning to use an old iron mining tailings basin for its own sulfide waste tailings is PolyMet’s original sin, a strategy that the DNR and PolyMet say can be made safe by adding a few relatively cheap, poorly planned and unproven remediation strategies. One DNR consultant in 2012 called the plan a "Hail Mary-type of concept” that “wouldn’t be allowed in other jurisdictions.”

One overarching problem cited by critics since the beginning, but approved by the DNR and never analyzed in detail by the Minnesota Supreme Court, is the overall design of the Flotation Tailings Basin (FTB), called an “upstream” dam for the way its layers are stacked progressively to the upstream side.

A host of famously catastrophic upstream dam failures have occurred in the past decade. One global study found that nearly 20% of active upstream dams had a reported stability issue. In 2020, Science magazine called upstream dams "a risky design" citing their "failure-prone approach" where the "... dams are built in stairlike stages, heading upstream over the accumulating tailings. Part of the weight of each added step is borne by the tailings below. This approach is often the cheapest, because the tailings serve as construction material.”

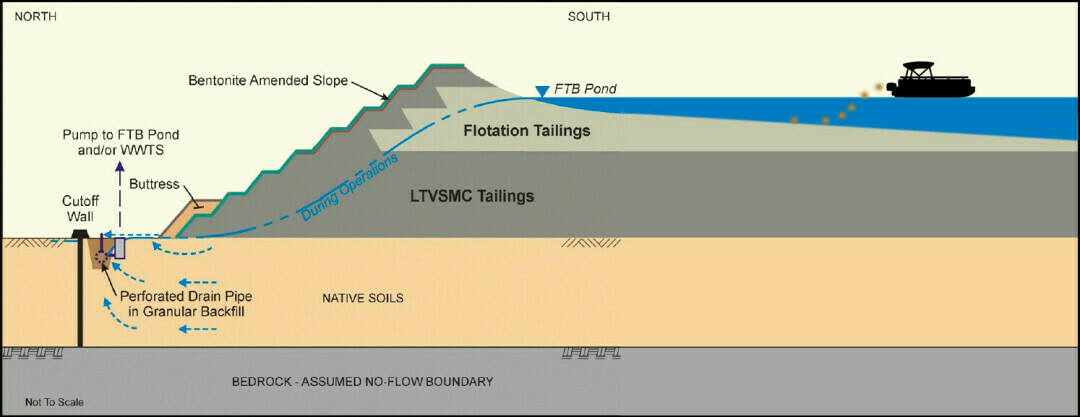

“Often the cheapest.” When an upstream dam design is used for sulfide mine tailings it can be even more dangerous, as polluted fluids could build up inside the basin much faster and higher because, for the dam to work correctly, nothing should escape from the bottom and sides. PolyMet’s proposed solution is a seepage collection system that would collect toxic waste near the bottom of the tailings basin and pump it back into the top.

The walls of upstream dams can also potentially become waterlogged, eventually to the point of collapse due to liquefaction. To drive that point home, Science quoted a geotechnical engineer who stressed that upstream dams can be safely operated, but not in areas that are wet and/or subject to seismic activity, two conditions present in the NorthMet area. A DNR dam safety engineer wrote in a 2010 email, for example, that "Minnesota experiences a magnitude 4 to 4.5 earthquake about every 20 years."

PolyMet has also claimed that the tailings basin will not pollute groundwater, and that the bedrock under the tailings basin is a continuous "no-flow boundary.» You could read that as a fancy way of saying no contaminated tailings drainage will seep through the rock under the basin. The company also claims it will prevent nearly 100% of any seepage that does occur from reaching surface and groundwater outside the basin.

The key to accomplishing this is connecting new semi-permeable slurry barriers called “cut-off” walls, partially made of soil and bentonite clay, to the granite bedrock that underlies the FTB using a process known as keying (similar to mortising).

PolyMet’s plan assumed the ground beneath the basin is continuous, high-quality granite. If they hadn’t made those assumptions, likely unwarranted, a lot of time and money would have been needed to both figure out the location and nature of the bedrock, and on remediation efforts needed to contain tailings seepage.

For its first two attempts at an Environmental Impact Statement, PolyMet didn’t do any drilling beneath the tailings basin pond or around its perimeter to characterize the ancient bedrock that the cut-off wall would need to be keyed into, and that would presumably prevent seepage from the bottom of the pond into the surrounding wetlands.

Geologist J.D. Lehr formerly worked for the Minnesota DNR and is an expert in the geology surrounding the NorthMet project. “PolyMet didn’t know, and still doesn’t know the nature of the bedrock beneath the tailings pond,” he said. “The geology of the area is much more complex than PolyMet has portrayed.”

Lehr produced a 63-page report for WaterLegacy based on his knowledge of the area, filings from the DNR and PolyMet’s own drilling records.

In response to critics, PolyMet finally did do some drilling in early 2014, but “didn’t drill beneath the actual basin pond, an area that is critical to understanding the hydrology and geology of the site” Lehr said. “And the drilling results they eventually got, from around the perimeter of the tailings basin, do not support PolyMet’s plan to build the cut-off wall as described.”

For example, in a quarter of the attempted bore holes on the north side of the basin engineers failed to even find bedrock, because of so-called “artesian” conditions – where the holes filled with pressurized and sometimes flowing water.

Lehr said engineers found artesian conditions across the north and west sides of the tailings basin that were so extreme that, even in late winter, water was bubbling to the surface, creating open water conditions that precluded some of the planned drilling. The amount of water coming from one borehole was extraordinary, flowing with “...approximately 10-12 gallons per minute within the upper foot of the granite.”

Drilling records for the north side also showed curious disparities in the depth where bedrock was encountered. For example, along a mile-long stretch engineers didn’t find any bedrock, even though they drilled to 35 feet deep. Yet on one side of that stretch they found bedrock at 50 feet, and on the other side they found bedrock as shallow as three and a half feet.

Those wide variances in bedrock depth suggest, Lehr says, that in some cases “engineers may have drilled into giant granite boulders, known to be in the area, not bedrock.” PolyMet itself has run into boulders as big as seven and a half feet in diameter, and miners at the nearby Peter Mitchell mine have encountered boulders as big as 14 feet in diameter.

NorthMet would also be required to operate a french drain-type system for the tailings basin that they say will collect 100% of the seepage through the pond’s bottom and walls, and pump it back to the top, for an indeterminate length of time. Court documents put the amount of waste that would have to be caught and pumped at about 300 million gallons a year.

The system is needed because the tailings and water in the basin create an outward-facing water pressure that needs to be reversed to prevent uncontrolled seepage through the sides and bottom of the basin.

When operating for iron mining tailings the basin relieved that pressure through seepage, but that won’t be allowed for sulfide mining. The basin would risk both seepage of polluted water through the bottom and sides of the dam, and possible liquefaction and catastrophic failure if either the cut-off wall or pumping systems fail any time during the lengthy reclamation process.

If the NorthMet tailings pond should ever fail millions of gallons of sulfuric mining waste would flow north through Trimble Creek directly into the Embarrass River, about two miles north.

Regulatory success short lived

At one point in early 2019 NorthMet had actually secured approval from the agencies for five crucial permits required to start mining: the permit to mine and two dam safety permits from the Minnesota DNR in November 2018, the National Pollutant Discharge Elimination System permit [water pollution] issued by the Minnesota Pollution Control Agency in December 2018, and a wetlands destruction permit, needed to bulldoze the forest over the proposed open pit mine, issued by the Army Corp of Engineers in March 2019. But the regulatory winning streak didn’t last long.

Responding to appeals from multiple parties the Minnesota Court of Appeals first issued a stay on the water pollution permit for PolyMet in August 2019, and the next month issued stays on the DNR›s permit to mine and dam safety permits. Then, in January 2020, the appeals court overturned the permits outright and ordered a contested case hearing on multiple issues before an administrative judge.

This presented the DNR with another opportunity to do the right thing. In the 10 months leading up to its approval of the permit to mine it had received petitions for contested case hearings on the very issues cited by the appellate court. Now a judge was saying it had to hold one. But the DNR, allied with PolyMet, appealed the appellate court›s decision to the state Supreme Court in February 2020, and the following month the court agreed to hear the appeal.

And even though, in the end, the Supreme Court supported enough of the appeals court decision that a contested case hearing was eventually ordered and the permit to mine remained suspended, its logic in reversing most of the appeals court decision illustrates the need for new legislation to deal with the unique dangers of sulfide mining.

DNR says virtually no one can contest its conclusions

One part of the DNR/PolyMet plan to get the NorthMet project up and running was to legally prevent virtually any citizen in the state from questioning their scientific conclusions in court. The DNR had good reason to try this tack: Each time one of the mine’s three crucial permits has gone before a court – one where people had to testify under oath and answer questions before a judge – they were overturned, where they remain to this day.

For contested case hearings state law says “Any person owning property that will be affected by the proposed [mining] operation...” can petition for a contested case hearing “...on the completed application.”

After the PolyMet draft permit to mine was issued by the DNR in 2018, the environmental nonprofits WaterLegacy and MCEA did just that: They filed for contested case hearings, based on the legal standing of their members, over many issues raised in the document.

WaterLegacy had argued in a 2018 filing to the DNR, for example, that, "Reclamation, closure and postclosure maintenance of the tailings waste facility...fail to comply with Minnesota law.” This is the same issue that eventually caused the Supreme Court in 2021 to both overturn the permit to mine and send it back for a contested case hearing.

Nevertheless, later in 2018, the DNR granted PolyMet its permit to mine, and simultaneously published a “Findings of Fact,” which answered a number of the petitioner›s questions, including the primary one: Were they going to get their hearings? The answers were all "no," and the main reason was that the DNR had determined that none of the contested case hearing petitioners had standing.

The DNR argued in its Findings of Fact, and in filings to the Supreme Court, that the phrase "owning property" meant only people who basically lived adjacent to the mine plant or basin could file for a contested case hearing. And then only those who could prove that they would "likely" be "substantially" affected by the project could file.

The Supreme Court had none of this white-shoe lawyering, paid for by more than $12 million appropriated by the Minnesota Legislature to the DNR for "legal costs" between 2016 and 2021. A spokesman for the DNR told us that "$2.9M was paid to an outside law firm" for PolyMet costs between 2004 and 2024, but that doesn’t square even with the $4.4 million allocated by the legislature for "legal costs related to the NorthMet mining project” in 2016 alone.

In any event, the Supreme Court rejected the DNR’s attempt to deny legal standing to nearly all Minnesotans, writing that “This interpretation, however, asks us to add terms to the statute that the Legislature did not include, which we do not do.”

This wouldn’t be the only time courts reversed PolyMet and the Minnesota state agencies on the NorthMet project over their legal hair splitting.

Supreme Court punts on dangerous upstream dam design

Of all the issues the Supreme Court considered that the appellate court had raised, it decided three in favor of the environmental groups and the tribes, and eight in favor of the DNR and PolyMet. One significant reversal by the Supreme Court was the appellate court’s requiring of a contested case hearing on the upstream dam design of the Flotation Tailings Basin.

The court admitted that the environmental nonprofits Minnesota Center for Environmental Advocacy (MCEA) and WaterLegacy had demonstrated critical expert opinion and recent incidents where “...upstream tailings dams catastrophically failed, resulting in widespread pollution and significant loss of life.” But that’s as far as the court went in actually considering evidence of the proposed dam’s potential design problems, as it ruled the DNR had “adequately explained how it derived its conclusion.”

One might accept this reticence to grapple with the actual, real-world competing claims surrounding the Flotation Tailings Basin if the court had ordered a contested case hearing to get at the truth of the matter. But the court merely observed that if one takes the DNR and its consultants’ word for it, the tailings basin will be perfectly safe.

But what if the DNR and its consultants have been spinning the data? On issues of geology and engineering related to the tailings basin, there are serious questions about basic facts.

“The number one takeaway from my report on the PolyMet FTB,” geologist Lehr says, “is the degree to which Barr Engineering [PolyMet’s engineering firm] was scientifically dishonest in the way they represented the geology and hydrology of the area and how the DNR accepted this. They downplayed the artesian conditions, overestimated the uniformity of glacial sediments overlying the granite bedrock, and underestimated its weathered and fractured condition. Barr painted a picture of the bedrock which they had no way of knowing.” Barr’s name appears dozens of times in the NorthMet permit to mine.

A spokesperson for Barr referred us to NorthMet owner NewRange, whose spokesperson declined to answer any questions citing ongoing litigation. The DNR told us in response to our questions that it “ ... took its review of the NorthMet proposal very seriously, applied rigorous independent scientific analysis and carefully applied, for the first time since their creation, Minnesota’s nonferrous mining laws.” Other experts disagree, arguing that PolyMet and Barr didn’t even employ common geological mapping tools successfully used in the area for decades.

Tony Runkel, the interim director of the Minnesota Geological Survey and an expert on how groundwater flows through bedrock, expressed reservations similar to Lehr›s about the tailings basin in 2014, when he submitted comments on the DNR›s 2,169 page PolyMet Supplemental Draft Environmental Impact Statement (SDEIS).

Runkel wrote that other investigations into groundwater flow in fractured rock conditions “...routinely use a number of well-known techniques that were not applied in the hydrogeologic studies at the NorthMet ... tailings Basin area,” and that, when those tools have been used in these kinds of conditions elsewhere in the region, the “...results support hydrogeologic conceptual models that differ substantially from those ... described in the SDEIS.”

In his comments on the final Environmental Impact Statement from 2015, Runkel pointed out that “routine [geological modeling] techniques...suggested in my (and other) 2014 SDEIS comments to improve the NorthMet site characterization were not employed.”

He explained that unidentified “...enhanced [water] flow along fractures [in the bedrock] would lead to significantly shorter predicted travel times than currently estimated in the FEIS.” That’s geologist-speak for waste water at the bottom of the tailings pond could move faster through the bedrock than anticipated by the DNR.

Runkel concluded that a clearer picture of the bedrock could have been achieved by “...including information derived from a number of well-established, common practice techniques that provide greater insight into [water] transport through fractured bedrock.”

The forever toxic pond and the magic bentonite cap

The two issues the Supreme Court eventually affirmed from the appellate court had to do with PolyMet’s plan to reclaim the basin site after mining operations have ceased, 20 years into their plans. These are similar to the issues raised by the Environmental Protection Agency way back in 2010.

Even Minnesota’s relatively weak mining laws require that so-called “reactive waste” be reclaimed in such a way that either changes the waste so that it is no longer reactive or prevents “substantially all” water from flowing through or over the waste, to prevent the creation of sulfuric acid and toxic metals drainage. Since PolyMet has no plan to change its reactive waste, its only path to obeying state law is to not allow water to infiltrate the tailings, forever.

To accomplish this PolyMet proposed what critics have derisively called the “pooping pontoon,” as the plan calls for, after mine closure, a boat floating on top of the tailings basin to drop a bentonite clay mixture into the water, where the DNR claimed it would magically make a permanent, water proof barrier covering the reactive tailings and forever prevent water from infiltrating them.

The Supreme Court wrote in its April 2021 decision that the DNR provided no proof for its assertions that the bentonite cap would work:

“...references to bentonite in the FEIS consist of descriptions and objectives of the bentonite amendment and conclusory statements about its effectiveness; there is no analysis of the scientific basis for the DNR’s assumptions. Further, the single study on which nearly all the DNR’s findings of effectiveness rely is not in the record.”

And that the agency’s “... own experts and external consultants ... contradicted the DNR’s finding on effectiveness,” with one actually opining that the “... methods and assumptions used to place the bentonite and to control the infiltration and tailings saturation are unsubstantiated, and wishful thinking. We do not believe it will function as intended...”

So the DNR offered no proof that the bentonite cap would work, its own consultants called it “wishful thinking,” and the only study it cited wasn’t in the record.

And call us crazy here in Minnesota, but we’ve passed laws that are meant to ensure that when mining companies make a big mess on their way to big profits they don›t leave the rest of us holding the proverbial bag. In their permits mining companies are required to say how long it will take to permanently reclaim their sites:

“The DNR must include in the permit ‘the term determined necessary by the commissioner for the completion of the proposed mining operation, including reclamation or restoration...’”

and the DNR’s administrative rules, which carry the weight of law, specify that the permit term for a sulfide mine

“... shall be the period determined necessary by the commissioner for the completion of the proposed mining operation including postclosure maintenance ...’”

Here the DNR tried to pull another fast one in the permit to mine, where it essentially said the reclamation “term” would end when the cleanup was done.

“The planned mining and reclamation activities will be completed in approximately the year 2072 with long-term maintenance and active water treatment continuing after that date until such time that continued compliance with the Minnesota Rules 6132.2000 to 6132.3200 has been established and the necessity for postclosure maintenance has ceased.”

The Supreme Court rejected this circular logic from the DNR:

“The DNR argues that the plain meaning of the word ‘term’ does not require a permit term to be for a fixed, calendar-based duration.. we conclude that the meaning of ‘term’ in Minn. Stat. 93.481 refers to a fixed period of time... And we agree with the court of appeals that the DNR erred in issuing a permit that did not include a fixed term.”

So for just how long would Minnesotans have to treat NorthMet’s mess? “Early documents included a period of 100 to 200 years,” geologist Lehr says. “But all time estimates were removed by the time of the final permit.”

Jennifer Saran, then PolyMet’s director of environmental permitting and compliance, told MPR News in 2014 that "...estimating how long water treatment will be needed is beside the point because the company will offer financial guarantees to treat polluted water – forever if necessary.”

Forever would be about right. One way of measuring the time period needed for reclamation is to simulate inputs into the water treatment system, which will be needed to prevent the pond from overflowing.

“They tested the inputs for the wastewater treatment system for 100, 200 and 500 years, and they were all basically the same,” Aaron Klemz, strategic director for MCEA, tells us. Leaked 2012 emails between a DNR consultant and DNR employees suggested the active cleanup period could be at least 900 years, and that without “perpetual maintenance” the dam would fail.

A spokesperson for the DNR said the agency disagreed with the court’s ruling, telling us in an email that the “...DNR had taken the same approach it had used for decades for taconite facilities and applied a performance-based rather than numeric term.” But NorthMet wouldn’t be a taconite mine, and the Supreme Court took up the issue “de novo” – or like it was the first time they’d heard it.

It didn’t have to go far to rule against the agency, writing that “In interpreting a statute, we construe words ‘according to their common and approved usage’,” adding that “...the word ‘term’ is not the type of language that is so technical in nature that we need to rely on the DNR’s expertise to discern its meaning,” and that “...the notion that a ‘term’ is a fixed period of time is uniform across various dictionaries.”

Specifically relating to so-called “performance based standards,” the court wrote that “We do not find the DNR’s indefinite, performance-based term to be a reasonable interpretation of the word ‘term’ as used in the context of the statute.”

The northwest corner of Big Sandy Lake flows into the Mississippi River about 10 miles northwest of the proposed Talon sulfide mine in Tamarack, Minnesota. If the mine contaminated water it could flow into Big Sandy two different ways – through the Tamarack River, north of Tamarack, and through a series of lakes and rivers west and north of the proposed mine.

Contesting the contested case hearing

The Supreme Court took the appellate court’s strong ruling against PolyMet and the DNR and turned it into an 8-3 win for the pair. The three wins (including standing) for the environmental groups and tribes were enough to force a contested case hearing, but the DNR then predictably used its many wins to narrow the scope of the hearing to just one issue: Whether the bentonite cap would work as required to prevent water from traversing the reactive tailings.

Still left unconsidered would be the many unanswered questions about the project cited by the appellate court as deserving contested case hearings, including the upstream dam design, questionable financial assurances given by PolyMet, and true ownership.

Finally, in March, 2023, two years after the Supreme Court ordered it, a narrowly construed contested case hearing was finally held in front of Administrative Law Judge James E. LaFave.

The reason for the hearing, as the DNR put it, was to clarify a “...single issue: whether the bentonite amendment at the tailings basin ‘is a practical and workable reclamation technique that will satisfy the DNR’s reactive waste rule...’”

Or, more succinctly, would the bentonite “...permanently prevent substantially all water from moving through or over the mine waste...” LaFave made it clear it was the “DNR that had ‘the authority to identify the issues and the scope of the contested case hearing.›»

Eight months later, in November 2023, LaFave handed down his recommendations. In it he lays out “five specific fact disputes” surrounding the case that his office told us were worked out between the parties in a pre-hearings conference. In reality the environmental nonprofits and the Fond du Lac Band of Lake Superior Chippewa had filed objections to the way the DNR had structured the hearing, but LaFave had denied their requests.

The identified fact issues were related to how the bentonite mixture would be applied, its effectiveness, how it should be evaluated, whether it would degrade over time, and how PolyMet would ensure that effectiveness over time.

LaFave’s decisions, which are technically “findings of fact, conclusions of law, and recommendation[s]” to the DNR commissioner, read like a whodunnit. He goes through the five fact disputes, and agrees with the DNR and PolyMet on all of them, until he writes, “Despite those recommendations, the Administrative Law Judge also recommends that the Commissioner find:”

• The bentonite amendment is not a practical and workable reclamation technique

• The bentonite amendment would not help ensure that the NorthMet Project permanently prevents substantially all water from moving through or over the reactive tailings as required by Minn. R. 6132.2200, subp. 2(B)(2) (2023).

And that “...the Administrative Law Judge recommends that the Commissioner DENY PolyMet’s Permit to Mine application.”

Turns out that after days of hearings exploring everything bentonite LaFave seized on one agreed upon set of facts to decide the case:

“It is undisputed that water seepage will occur after closure. PolyMet estimates that:

• 160 million gallons per year will seep from the pond;

• 73 million gallons per year will seep through the beaches; and

• 65 million gallons per year will seep from the dams.

This means that, by design, 298 million gallons of water will move through or over the tailings every year.”

In fact it was Tom Radue, an employee of PolyMet contractor Barr Engineering, who confirmed this to WaterLegacy’s Maccabee at the hearing:

BY MS. MACCABEE:

Q. I’d like to change gears now, make something a little simpler. If we could turn to Mr. – to your rebuttal testimony... And in your – in this rebuttal testimony, based on the pond area of 905 acres and the basin average depth of 8 feet, you calculated that there would be 160 million gallons a year of seepage annually lost through the pond bottom each year, correct?

A [Radue]. That is correct. [ID added]

The Reactive Mine Waste rule covering this requires a mine to "...permanently prevent substantially all water from moving through or over the [reactive] mine waste...»

The DNR and PolyMet argued in response to Radue’s admission that it wasn’t the total amount of water that moves through the waste that matters, but rather the fraction of possible water that moves through it.

Judge LaFave put it bluntly that “Petitioners maintain that whatever the term [preventing] ‘substantially all’ means, that is not it. The Administrative Law Judge agrees.” He then explained that "298 million gallons is an enormous amount of impaired water.”

Today the permit to mine is back in the hands of the DNR commissioner, who must decide how to digest both the administrative law judge’s decision on reactive waste and the Supreme Court’s order to set a real reclamation term.

Tom Landwehr is long gone, but the things he set in motion are still playing out. The current DNR commissioner, Sarah Strommen, took part in the litigation so ethically she will not be the “decision maker” as to how the DNR acts on the administrative judge’s recommendations. Instead, she appointed Grant Wilson, DNR Region 3 Director, to decide how to proceed on the NorthMet permit to mine.

Supporters are furiously fighting behind the scenes at this very moment to provide Wilson some justification to at least stay the administrative judge’s decision.

On the Supreme Court’s requirement for a fixed term of reclamation, the DNR makes it sound like just a routine thing: "The DNR is currently considering how best to incorporate a fixed term and will seek public input on draft term language for the permit to mine at a later date.» Some estimates for the post-closure period have gone into thousands of years.

The seepage problem is just as daunting. How do you stop 300 million gallons of water from passing through the tailings every year?

For now, at least, it looks like NorthMet is dead in the [waste?] water. But don’t count it out, says MCEA’s Klemz. “Companies like Glencore work on very long time frames – waiting a few decades to cash in is quite normal for them. They might be at a stalemate for now, but they’ll likely be back.” And there are at least two sulfide mines waiting in the wings that don’t carry the tailings basin baggage that sank NorthMet.

Sulfide mining a hall of mirrors

The politics of sulfide mining in Minnesota is like a hall of mirrors. Nothing is what it seems, from the upside-down structure of who would benefit from the profits, to the question of who would clean up the inevitable mess, to the simple facts of who owns the mining companies. Attributing responsibility for the current situation to political parties can be challenging as well.

Democratic state Senator Jennifer McEwen (DFL-Duluth), for example, has proposed legislation called Prove It First (PIF), which would essentially put a 20-year moratorium on sulfide mines in northeastern Minnesota, until it had been done safely somewhere else.

But it’s also been two consecutive Democratic governors who have appointed the DNR and MPCA commissioners who have gaslit the state’s citizens to approve sulfide mines. And both parties and both houses of the legislature have prevented any new sulfide legislation, including PIF, from even getting a hearing for more than a decade.

Numbers compiled by Friends of the Boundary Waters (FBW) are even more confounding, showing that 75 out of a total of 201 Minnesota state legislators, all Democrats, support McEwen’s proposal. Chris Knopf, Executive Director of FBW, said he’s had talks behind the scenes with three Republican senators. “It’s a bipartisan challenge,” he said, while admitting that zero Republicans are on record supporting the proposal.

Of course, there’s more to political support for mining than head counts. Mining is one of the traditional economic engines on the Iron Range and northeastern Minnesota, and it’s culturally and historically intertwined with the people who live there. There are trade unions involved in mining which tend to support the Democratic party and pull it toward the mining side. And just about everyone thinks the 2010 U.S. Supreme Court case Citizens United empowered the multinational mining companies.

In the background of it all stands former President Trump, who if reelected could try to wreak havoc by declaring emergencies to get sulfide mines operating wherever he wants, perhaps even in the BWCA. “He could try that,” former Governor Arne Carlson told us. “But he’d find himself immediately in court. Minnesota has a right to a licensing procedure.”

WaterLegacy’s Maccabee was less sanguine about a Trump return. “If you capture all three branches of the federal government, then anything can happen. Executive abuse of power, a corrupt court and a legislative branch that would not impede these actions is a recipe for disaster.”

Which is all the more reason, Senator McEwen said, to get on with passing Prove it First. “We need to put up all the guardrails we can.”

To that end Ann Cohen and JT Haines of the Minnesota Center for Environmental Advocacy have come up with a handful of additional recommendations for new mining laws that would address some of the issues courts have dismissed in the NorthMet case, such as banning upstream dams and tailings basins in fragile ecosystems, giving the DNR enforcement power, requiring the re-certification of permits, strengthening financial assurances and clarifying true corporate ownership.

Those proposals don’t get at the unwarranted discretionary power held by political appointments at the Department of Natural Resources and Minnesota Pollution Control Agency, nor the state’s antiquated and broken process for regulating mining. But modern laws designed for the task at hand would at least give courts clear authority to protect Minnesotans and their water from bargain hunting foreign corporations until our elected officials once again do their jobs.

Can sulfide mining be done safely in the sensitive areas in northeastern Minnesota? Maybe. If you ask an engineer she’ll tell you that just about any environmental engineering problem can be solved – given the proper amount of resources and time. But current efforts to mine low grade ore on the cheap in environmentally sensitive areas, and skirt or ignore the state’s paltry sulfide mining laws haven’t panned out, even as the state’s executives, legislative branch and courts have bent over backwards to make it happen.

The problems with the PolyMet tailings basin, obvious for a decade and a half, have once again given the Minnesota Department of Natural Resources a golden opportunity to do what it should have done from the start and reject this project. Will the agency take this opening to protect the waters of northeastern Minnesota and Lake Superior?

Rob Levine is a Duluth native and former staff photographer at the Minneapolis Star-Tribune. He now works as a freelance photographer, writer, editor and web developer.