'I tried everything'

Officer Stans Nesgoda wanted to stop the 1920 lynch mob

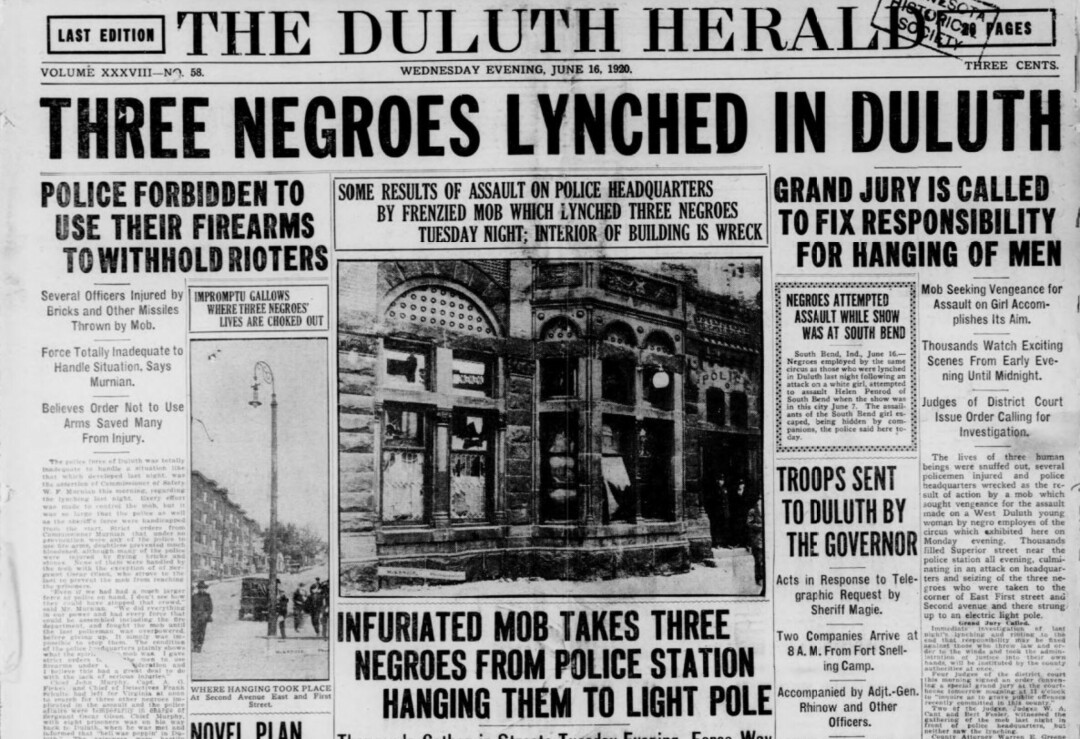

The Duluth Herald of June 16, 1920, the day after a crazed mob attacked the city jail and lynched three innocent men for a crime that never took place.

Born in Duluth, and now living in New York City, my name is Tiah Balcer. But, it wasn’t supposed to be Balcer, as I discovered who my biological father was four years ago through DNA. My Polish family name really was Niezgodka, Americanized to Nesgoda shortly after Piotr arrived in Duluth through the port of New York from Poznan, Poland, in 1884.

There is a history in Poland of the Niezgodka surname being earned, marked by those unafraid of dissension and willing to stand up for what they believe in, even against the popular opinion of the masses or the powers that be. The name itself means “disagreement,” or, if you prefer the more literal translation, “woman not apt to make peace.”

Four years after Piotr arrived in Duluth, he had a son, Stans Nesgoda, who was sworn in as a Duluth police officer in 1915. And yours truly, four generations later, is the granddaughter of the granddaughter of Stans Nesgoda.

And I would like to talk about the truth.

On June 15, 1920, Officer Stans Nesgoda arrived to police headquarters around 9:30 pm to chaos, called in early with the other officers from the overnight shift by Sergeant Olson. A crowd of approximately 5,000 members of the public, packed three blocks wide, had stolen hoses from the fire department and turned them on the officers, throwing bricks. This was following men driving around town in a truck all day, holding a rope, and announcing to other citizens that there would be “a neck tie party” in reaction to a white woman concocting a rape story.

Breaking out windows, hundreds of citizens stormed into a flooded headquarters, some armed with guns, packing the building like sardines, leaving a large hole in the wall by the entrance. The police fought the public against gaining entry into the jail cells for hours.

Rioter Gilbert Henry Stephenson made his way up to the cells of Eli Clayton and Elmer Jackson, where Officer Nesgoda, Sgt. Olson, and a few other officers tried to convince the mob that no one was in the cells, knowing Clayton and Jackson couldn’t be seen from the angle, hiding under their beds. Stephenson proceeded to use a sledgehammer to break into the cells of the falsely accused, eventually raising it at Officer Sundberg. Nesgoda then proceeded to save Sundberg from Stephenson’s sledgehammer, getting a good look at Stephenson’s face for identity while doing it, contributing to Stephenson’s conviction for rioting by providing testimony against him. Unfortunately, the charges and punishment were not greater, as serving a year for rioting was without doubt salt on an open wound, devoid of any whiff of social justice.

Nesgoda and Sundberg were then informed that two men behind them had guns. The officers were then pushed out of the cell block area by the public, ultimately unable to save the circus workers.

Officer Nesgoda testified, “I tried everything.” Those were his exact words. His words never included any N-words that were so pervasive in much of the testimonies about the lynchings. Indeed, Nesgoda had no roots in the monstrosities of Colonial America and was likely drawn in by the idea of a police force that, upon the year of his hiring, had relieved itself of dozens of corrupt personnel and was in need of replacements.

In his many years of other police activity documented by the local papers, he likewise had no indication of causing any social grievances by any time period’s standards, which ought to be identical anyway, as the essence of our being demands humane treatment irrespective of the year.

Officer Nesgoda pulled his gun. Knowing that shooting would lead to more shooting, Nesgoda stopped short of pointing it, not wanting to ignite a gun battle. The officers would not be able to try to achieve peace if they were dead themselves, unable to quiet the violence. Violence just leads to more violence. This reasoning was conveyed in original source documents currently available for free through the Minnesota Historical Society, but it is seemingly left out of secondary sources, which tend to perseverate the worst of the statements made by other officers, despite it being common knowledge that, just because a number of people believe something, doesn’t mean everyone associated with them believes it.

As public speaker, Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie, warns in one of her TED Talks, “The Danger of a Single Story,” there are actually many different stories to all of life’s events, and the truth is in the details of each individual you can get to know. Nesgoda arrived approximately one and a half hours after orders not to shoot were given.

Let’s say you yourself are among 20 against 5,000. You just showed up, as the rioters are violent, armed and destroying the building. You have six shots in your gun – a lot less than the homicidal crowd has in theirs, as they are throwing bricks and trying to kill your coworker with a sledgehammer. You do not have modern-day conveniences for breaking up a riot, such as tear gas. You still believe you’d use your six shots? It would be your last move on this Earth, and the few trying to stop it would be dead, too. Who, then, would stop it? Battling the public the hard way apparently seemed the choice with more hope.

Don’t get me wrong, the higher ups in particular in the station were clear about what they thought a black life was worth compared to a white life. The statements they made caused more societal damage than mere disgust. What if your boss thought that? Would you let it be your legacy that you must have thought that, too, since you work with him? Too often in public discourse and secondary sources, the highlighted question about Duluth’s 1920 lynchings is, “Why didn’t the police put a stop to this?” But, in regards to this specific atrocity, the primary question should be, “How could the public perpetuate it?” The police, in fact, fought an enraged and delusional public for hours against gaining entry into the jail cells.

So, what is the moral of the story in this horror? In doing something about racism, we should understand that no person is all bad or all good. People are human beings to be treated as per their individual sentience. Let’s start there.

Policing is a profession. They’re not all bad either, and they’re not all good either. In doing something about racism, we should understand that generalizing is part of the problem. The public, that day in 1920, thought of course all black men are apt to rape white women, as police and judges pleaded with them to let the falsely accused have a fair trial. And the narrative now is that of course all police were racist in 1920 – and perhaps now, too.

If we want the healing to begin, we could strive to prevent the word “all” from being thrown around too loosely, as more literal souls among us might believe the myth of its face value. Which Duluthians in 1920 took the time to get to know Clayton, Jackson and McGhie? And can you yourself now say that you have taken the time to try to get to know a police officer? If you are not already a part of it, have you put in the time to get to personally know any members of Duluth’s black community, which is a part of your own? Why do people exhibit a proclivity to form theories about groups whose individuals they do not take the time to get to know? We should take a look at each other’s individual character, whether a civilian or a member of the police, avoiding the danger of a single story about any group, lest the generalizing serve to keep superfluous and unproductive tensions alive and someone gets hurt.

But, there are actually countless lessons to be learned here. As a matter of fact, if my maternal family would have had it their way, I never would have known I descended from Stans Nesgoda.

My biological father and biological half-sister were hidden literally right in front of my face growing up, a fact revealed through DNA during the Summer of 2020. I knew them. I swam in their pool. I visited their cabin. They didn’t even knock when they entered my house. But nobody thought it was necessary to tell me who my own blood was, only admitting to it once evidence was irrefutable.

So. To me, there is still a subconscious approach running like a theme through the town – a common thread running through so many problems – about how to handle your skeletons in the closet. Hide them, shut the conversation down, pretend something else is true, deny, deny, deny, filibustering and gas lighting all along the way. Even get angry if someone suggests the truth. (Anything but working through it to identify a conclusion that serves reconciliation.)

The same mechanism that denied Duluth its truth denied me mine.

The lesson is one of cover ups. Writing the story in a way that underestimates your own tolerance. Hiding the truth and hoping that makes it otherwise. Duluth’s lynching history was not known about until relatively recently because it was both actively and passively covered up for decades, and when it was initially uncovered, there was little interest for additional decades, and now a commonly heard reaction is that there is no point in talking about it. The city effectively stuck its historical head in the sand to forget what it did, then countless voices blamed it on police. A city that hides its ugly truth and doesn’t want to talk about it, hasn’t had occasion to reconcile, so what happened 104 years ago is still relevant. In the words of Dr. Phil, “You can’t change what you don’t acknowledge.”

Take this opportunity to ask yourself what secrets you have that you should be telling somebody in order to live in reality. What knowledge do you protect for no good reason that really belongs to the whole community or to someone else that is not rightfully yours to keep? In this country, we observe days for love, for taking a rest, for the new year, for remembering others and history, and even for playing pranks. When is Revelation Day? On what day do we reveal to others what they deserve to know and absolve ourselves of the heavy conscience we’ve carried senselessly? When is the day that it is okay to talk about what is uncomfortable to talk about?

To the Duluthians of my hometown, I present you with this message: You do not have to do what everyone else does, and you do not have to make the choices everyone else chooses. This applies to whether you are tempted to succumb to the worst kind of mob mentality, whether you talk about it afterwards, and telling the truth to your family members about who they are. You do not have to sweep your dirty laundry under the rug. It’s time for critical thinking.

Speak the truth over and over again with such persistence that people find it difficult to see the point in finagling. Get to know the individuals from the groups about which you habitually make commentary. The reality is that three men were lynched here. Patrolmen, some of the few trying to stop what the public did, were scapegoated. And I - am not Ms. Balcer.