Middle East in one word?

I start by saying the title question is an absurd impossibility. Knowing I’ll be quite wrong won’t stop me, however. But to reach a plausible one-word view I think I need begin with a crucial source around which an understanding might form.

In my view there’s a foundational element that must be considered. What might that be? Nothing more nor less than the holiest book of all time, so profound and elevated that I won’t even risk naming it in English because only in the original Arabic (so I’m told) can any understanding at all be achieved or appreciated.

Already we are quite far from one-word, but I’ll ignorantly soldier on. The number of completely insufficient English versions I’ve read do seem to agree on some particulars. The compilation (already a difficulty, but let’s continue) put together somewhat after events (another difficulty, but continue) is none-the-less the final revelation from a particular deity (I hesitate to name names) as revealed to a particularly perfect prophetic vessel. (No, this is not going to be simple or easy.)

Agreed on in general is the final revelation is a masterpiece of literature essentially supplanting previous revelations thus making it the last word. (That’s likely important, eh?) The final reveal provides universal unity by superseding any previous revelations, an intricate process repeated in the final revelation itself when later words abrogate earlier ones. How’s this?

Say at the start of a relationship your partner is dearest and best but later you quarrel and that partner deserves being eaten alive by bats. Consumed by bats is the final word. Period. But (I take a deep breath) being able to sort that out in the greatest work of literature is a daunting task, not to mention attempting it in English can’t do justice because only the original language works and is the only way to address the deity, another period.

We are nowhere near a single word understanding, are we? But be brave so we can face the other element of masterpiece giving the code or plan for life universally. There is no single word able to contain all that. But, soldier on anyway. When puzzled by a situation, my ignorance often suggests looking away to something further afield. Not only does momentary diversion suit me, but on occasion looking elsewhere can be fruitful.

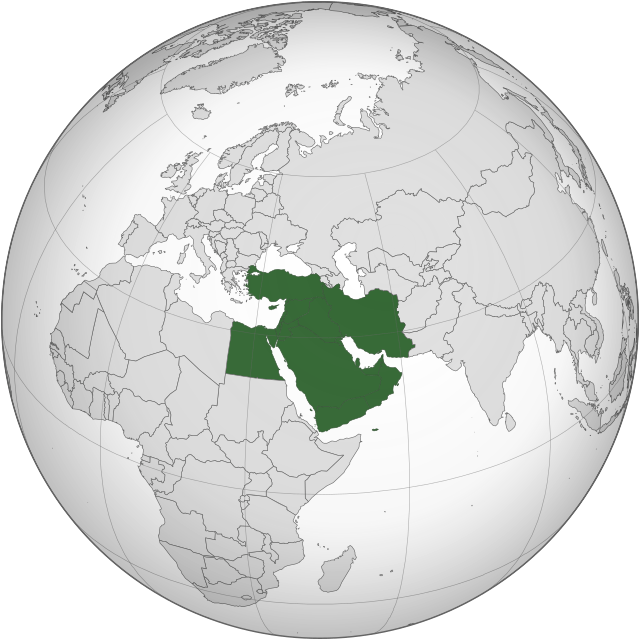

The ongoing, lately aflame, Middle East issue became official in 1948. Before that the issue of land and occupation went on in the British protectorate (not then an independent state from the sound of it) called Palestine. In my opinion the 48 carving up of the area to create a post-WWII and post-Holocaust Jewish state was rushed and flawed, but (big BUT) given the British just having gone through a subdivision of India into nations of separated beliefs there was maybe no diplomatic horizon other than be-done-with-it.

One thing to bring to mind looking far afield is the division of India into two Islamic and one non-Islamic nations was easily a much bigger deal. India, huge and potentially prosperous, could not exist with one belief seeking political control of the other. Specifically, one group did not accept the final decree of a code for all humanity applied to them. If there is a word that might apply and be useful, that word is theocracy.

Some, I’d say most every, of the beliefs on the planet can turn theocratic (religion equaling government), but only a few insist on it by routinely forming religious governments. For those who look in horror at the Inquisition as condemnation of the West, I politely suggest hunting heretics is the present reality in religious states in general. Religion having political or government power can’t help but be repressive (quite often hostile) toward heretics (opposing or questioning viewpoints).

Heresy has as much political as religious potential in its subtle, pervasive presence. I saw this on my visits behind the Iron Curtain where speaking freely and openly carried well-known risks. Watchful eyes of political or religious authorities are equally dangerous and destructive of society. Unity enforced is not unity at all. As happens, beliefs practiced in a system equipped with enforcement exhibit something other than unwavering universal truth. This is known as interpretation.

The final revelation, greatest work of literature experienced this soon after it came to be when believers split into two main factions still in existence. That side of things requires many more words than I’ve time for here, but at the very least the final plan for all people wasn’t universal for long. Reformers of the system tend to run into trouble as heretics. See how it works? Theocracy doesn’t like opposition. No room for reform in that inn.

Let’s say an inspired holy text frequently uses the terms struggle and fight. Does that mean an inner battle with self or outward war with opposing beliefs? Whatever answer you or I prefer does not wave away the reality there’s a hell of a huge gap between the two positions. One thing I’d point out is that sitting profoundly meditating on worthy thoughts offers no protection from outside forces. Plague or violence destroys equally. Understanding is a challenge.

How do we make sense of things? Thoughts are not themselves violent, but they can promote or incite brutality. A position of neutrality or tolerance meets a test if it accepts brutality as simply another act or aspect of humanity only superficially different from kindness. Good intent doesn’t necessarily end that way. Luckily, even in weak translations the great guide tells of triumphant times when the enemies of belief will be defeated. (A particular enemy is named in the texts, but why get picky just now?) At the time of victory the stones will cry out telling believers where unbelievers hide to “Kill him.”

This sentiment, I believe, is easily turned about to point the other way, suggesting to me targets of violence need be no more passive than their attackers.

As for the Middle East in a word, try Middle-East.