In my range

Gluttony

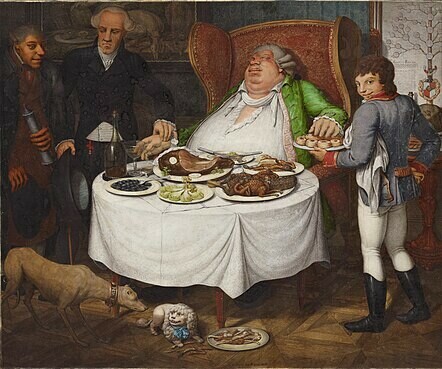

Gluttony

At age 14 I stood proudly outside need of assistance. A slim decade of awareness was enough to supply an encyclopedia of life experience. So I believed. Mom and dad’s expressions suggested otherwise, but why should I, a pimple of aspiring, pay heed to the past, the old and decrepit?

Fuzz-cheeked as my convictions clearly were, I had, so me thought, enough good backing to see me through much and then some. I had warm and colorful big-city Chicago family connections to thank for that. My family’s two sides gave a darn wide view of the greater world.

On mother’s side was a platoon of splendidly heavy eaters and drinkers. At times accused of being drunks, they stoutly defended honor and habits with words of life-loving endearment and conviction. And true enough, but who’d risk picking a fight with what amounted to a herd of hippos? At family gatherings of mother’s side a child learned early the wisdom of staying clear of the forks and knives flashing across the table. Food was reduced, you could say Hoovered to scraps and scrapings before the dinner chairs were fully warmed. Those were people who knew how to eat.

I could elucidate this as the behavior of Central Europeans faced with unaccustomed plenty as working class Americans. But that does not explain the glorious attention to richness of detail in their celebratory meals. Excess of richness, of volume and glorious plenty were much a part of the occasion as succulently done pork or pastry worked to flaky, fruit filled perfection. Let loose in America’s house of plenty, many on mom’s side left the globe around age fifty of heart and associated problems. Died young, but the family seemed to feel that was OK, a good way to go.

I was older, a college age annoyance, when a quartet from mom’s side came for a visit. With them they brought a “pan” of sweet rolls from a bakery they much loved and wished to share with us who normally didn’t see things in that volume outside a school cafeteria catering to bottomless teen hunger. There were a lot of sweet rolls put to table. Gusto eating from mom’s family cut that down to size with stunning speed. Perhaps you’ll recall the kind of waxy paper often associated with sweet baked goods as a liner and separation of one type from another. It was not long before the quartet saw to it that was near all that remained of the treats brought from Illinois. Waxy paper, odd dabs of icing leftovers and, of course, the peculiar watery blobs that are left over were all that remained.

Mom’s family were big people with large appetites. I worried that if the four moved suddenly to one side of our house they’d flip it over into the neighbor’s yard. Of course I exaggerate, somewhat. I’d not exaggerate saying they were generally nice and generous people, even toward a snotty and bewildered college smarty. There was a gulf between us, likely as much of my generating as theirs.

As for those on mom’s side who drank and played music, I saw little of them except at weddings and funerals when they came wholly into their own. A couple of 280-pound uncles doing battle on a dance floor is something a teenager won’t any time soon shake from memory. The same teen would be equally befuddled at the sloppy but sincere resolution that followed.

On dad’s side, another galaxy of counter-types, glowing appreciation of food and drink was replaced by gluttony of another sort. Dad’s puzzling family was split between opposites of quite good and honest and those not to be trusted with a piece of old bread. How and why is beyond me.

As a boy, dad gawked outside the hospital where the St. Valentine’s Day massacre bodies were unloaded. His younger brother, another gawker, saw crime-life as more interesting. Details of family corruption were kept from me, but it was pretty clear that if someone wanted a really good price on something, one or another of dad’s brothers would arrange the kind of wholesale known as stolen.

Dad, generally honest, gave in on occasion when something special at a not-to-be-believed price proved irresistible. I knew because he looked guilty afterward. Sure clue.

Mom’s heavy indulger side was easier to tolerate. For them I never grew an active aversion, not as I did for dad’s brother who made the trip to Minnesota to. Wait. You decide. –

Circumstances leading to Uncle’s visit are fogged, but not the final design. Dad, having expressed an interest in finding a used jeweler’s lathe was all Uncle needed to say he’d get one, a thing more likely in Chicago than here, and bring it. Dad, wishing to see his younger brother again, didn’t see blood in the water when Uncle suggested they trade. Through phone calls I believe Uncle knew what he’d ask in trade for a lathe that turned out to be junky. But, being many years since they’d last met, dad carried forward, oblivious.

Easing into the “trade,” Uncle expressed interest in some Aladdin lamps (a hobby of mine) I’d rehabbed and completed. There was the Little Abner mechanical toy band, pristine because I’d never been allowed to play with it. Add a beautiful pre-war Lionel 4-6-4 engine with crane, side dumpers, lighted caboose and unusual station. Above all Uncle desired my P.08, everything, including holster, original, correct and properly stamped. A low serial ending in 00 meant all small parts bore 00. I didn’t want Uncle to see or touch it. And I definitely didn’t want it traded. But. –

I was at work when Uncle left. Our houses adjacent, dad, the next day sheepishly confessed. Imagine my feeling. The pistol was gone. Dad hoped a lavish trade would lure his brother to visit again. Wrong. Uncle got what he wanted. He was not seen again. Years later when dad died Uncle called to ask “What’s up?” He didn’t come for the funeral. Uncle is understandably human, but a no less sad example.