Three takes on the Lonely Heart Killers

Shirley Stoler and Tony Lo Bianco as Martha Beck and Raymond Fernandez in The Honeymoon Killers.

“My story is a love story. But only those tortured by love can know what I mean. I am not unfeeling, stupid, or moronic. I am a woman who had a great love and always will have it. Imprisonment in the Death House has only strengthened my feeling for Raymond.”

Those were the last words of 31-year-old Martha Beck before she took her place in the electric chair at Sing Sing Prison on March 8, 1951, after her lover, Raymond Fernandez, had already died the same way for the murder of a 66-year-old Albany, N.Y., woman.

Raymond was a con man that Martha met through a lonely hearts club. Eventually she joined his con, which led to murder. For certain they were responsible for four deaths, but they claimed there were as many as 20. They were known as the Lonely Heart Killers, and filmmakers apparently love their story because there are at least three film versions, two of which (The Honeymoon Killers, 1969, and a Spanish version of the story, Profundo Carmesi/Deep Crimson, 1996) recently appeared in a collection of 30 true crime movies on the Criterion Channel.

The third version, Lonely Hearts (2006) is available on Amazon Prime.

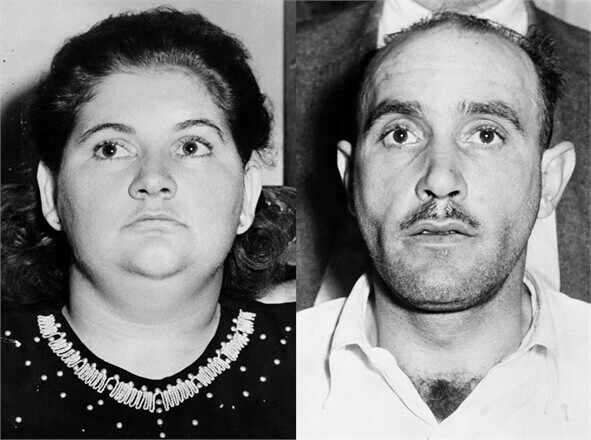

The real Martha Beck and Raymond Fernandez

Fernandez was born to Spanish immigrant parents in Hawaii in 1914. The family moved to Connecticut, and when Raymond was in his teens, he and the family moved to Spain. He married a Spanish woman and they had four children.

In 1945, when he was 31, Raymond boarded a ship to the U.S. without his family. During the voyage, a steel hatch fell on his head and fractured his skull. Those who knew him said the accident dramatically changed his personality.

By December 1946, he was living with relatives in New York City and had joined Mother Dinene’s Friendly Club, the lonely hearts club where he would eventually meet Martha Beck, who was working as a nurse and raising her two children by two different men in Sarasota, Fla.

Raymond traveled to Sarasota to meet Martha, thinking a nurse must have some money he could get his hands on. But Martha was poor and had failed to tell him about the children, so a disappointed Raymond quickly fled back to New York and better pickings.

Martha threatened suicide if he would not see her again, and since a dead body could bring him trouble, Ray invited her to visit him in New York. Martha visited him on a two-week vacation (without the kids), only to find upon her return that she had been fired from her job, so she showed up on Raymond’s doorstep with her two kids. He refused to accept the children, so Martha dumped them (some reports say with her mother, others say at a Salvation Army) and returned to Raymond and the start of their crime spree.

Raymond explained to her how he posed as a Latin lover to those lonely women in order to con them out of their money. And since they were now inseparable lovers, Martha accompanied him on these outings as his sad, loveless, overweight sister.

As incredible as it seems, Fernandez wooed and married several women with the imposing Martha Beck like a malignant Siamese twin at his side all the while.

While they went to their deaths claiming they had killed as many as 20 people, Beck and Fernandez were tried and executed for only one murder, that of 66-year-old Albany, New York, widow Janet Fay.

They were caught after doing away with their next victims, a young widow from Grand Rapids, Mich., and her 2-year-old daughter. Neighbors had grown suspicious about seeing Ray and Martha in the home, but not the woman and her daughter. The neighbors called the cops, who found the bodies of mother and child buried beneath wet cement in the basement.

Regina Orozco and Daniel Giménez Cacho as Latinized versions of Martha and Ray. The story has been moved to Central America in Profundo Carmesi (Deep Crimson, 1996).

However, Michigan did not have the death penalty, so the couple was extradited to New York to face capital murder charges there.

The movie versions begin with a true oddity, The Honeymoon Killers by Leonard Kastle in 1969, which opens with this written prologue: “The incredibly shocking drama you are about to see is perhaps the most bizarre episode in the annals of American crime. The unbelievable events depicted are based on newspaper accounts and court records. This is a true story.”

This is the only movie Kastle made, and he never intended to make this one. Opera was Kastle’s milieu, as composer, librettist and conductor.

The movie came about through Kastle’s friend, Warren Steibel, producer of William F. Buckley Jr.’s TV series Firing Line. A wealthy friend had given Steibel $150,000 to make a movie, which he had no experience at. His idea was to do a documentary-style movie about Beck and Fernandez, and he asked his friend Kastle to write the screenplay and help get it made.

Kastle conducted the research through newspaper accounts and court records, wrote the screenplay, and then tapped a promising young director to helm The Honeymoon Killers. Kastle had seen and enjoyed Martin Scorcese’s debut feature Who’s That Knocking at My Door?, so hired him.

But Kastle quickly decided Scorcese’s painstaking directorial style would quickly eat up his minimalist budget. After firing Scorcese, Kastle tried one other director before taking on the task himself.

The result is probably the best of the three movies dealing with the subject, although it completely avoids the issue of Martha’s children. It’s shot in stark black and white, always a plus in my book.

Tony Lo Bianca plays the balding Latin lover, who is introduced to his beloved hairpiece by one of his victims.

Martha is played by Shirely Stoler, whose other major role, in my opinion, was as the obnoxious Mrs. Steve in the first season of Pee Wee’s Playhouse (apparently she rubbed Paul Rubens the wrong way and was axed from the show after Season 1).

While attempting to fleece lonely women with Martha at his side, Ray’s work sometimes comes to naught when Martha’s jealousy flares and she exposes the unhealthy relationship she and Ray have, forcing them to move on to another victim.

Oh, the tangled webs we weave.

LoBianco’s Raymond is not as bald as the Raymond’s in the other two films, and the hairpiece idea is introduced to him rather than being an essential part of his performance.

Apparently the real Raymond was extremely sensitive about his baldness, and when his final victim, the Michigan widow, saw him without his hairpiece, he shot her.

The Raymond of Deep Crimson is far more concerned about his lack of hair, describing himself as a freak without his hairpiece, and there is a harrowing scene where the widow catches him sans toupee, but he does not kill her for that, just beats hell out of her and tries to drown her in a barrel of old oil.

Oddly, in The Honeymoon Killers it is Martha Beck, not the neighbors, who calls police to the scene of the double murder, and in Deep Crimson it is Ray who makes the call.

Bad hairpieces abound in Lonely Hearts (2006), including on detectives James Gandolfini (worst ever) and John Travolta.

The third film, Lonely Hearts, seems to be all about hairpieces. It tells the story from the viewpoint of two detectives played by James Gandolfini and John Travolta, both of whom are sporting weird hairpieces. Actually, Gandolfini’s might be the worst hairpiece in the history of film. It does not sit naturally on his head so you can’t stop looking at it.

I have more problems with Lonely Hearts than the toupees. What’s up with casting the svelte Hayek as the obese Martha Beck? And a couple of very open murders, such as the shooting of a cop, were not part of the Beck-Fernandez tally, yet they play here because why?

Added into the mix is Travolta living with the guilt of his wife’s suicide by gun in the family bathtub. It lacks the purity of intention of The Honeymoon Killers. Kastle and Streibel just wanted to tell us the unbelievable but true story of Beck and Fernandez, and they do, with less artistic license than the makers of Lonely Hearts.

Deep Crimson might adhere closest to the true story by including the children, the drop-off at an orphanage, Ray’s fear of being seen without his wig, and other details. But it veers off too, first by changing the names of the characters and second by placing them somewhere in Central America.

But guaranteed watching this trifecta of sad, lonely, disturbed people will make your own world seem much brighter and uncomplicated.