Why I was willing to cross the union

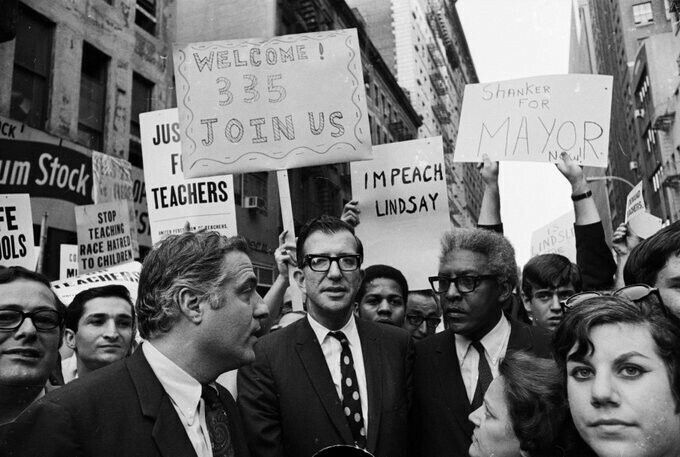

Albert Shanker, center

My August 12, 2021 Reader column about the book 36 Children explains what set me to looking for a level playing field for inner-city children. I never lived in one but I was enrolled in a Topeka, Kansas, elementary school that was integrated by the Supreme Court.

One day in 2nd grade I was unexpectedly sent out to the playground where I climbed to the top of the jungle gym and watched as a hundred black children marched to Loman Hill Elementary from their segregated Buchanan Elementary. I would be the product of a level playing field.

It was for this reason that I started with a low opinion of Al Shanker, an infamously combative man, who was the President of New York City’s teacher’s union. His fellow New Yorker, Woody Allen, mentioned him in one of his funniest movies, Sleeper. Woody’s character had slept through the end of the world. When he awoke in a very different world after nuclear annihilation, he asked what had happened. He was told, “A man named Albert Shanker got hold of a nuclear warhead.”

New Yorkers loved it, but I only knew that Al had a big fight with the union’s black teachers. I was automatically on their side.

My feeling about Shanker changed before I began battling to get on the Duluth School Board. Shanker had grown reflective in the face of what was billed as the “national report card” on America’s public education. A report called “A Nation at Risk” said too many American kids weren’t learning – kids like those in the book 36 Children.

Shanker had gone to Germany and watched a new generation of teachers guiding their students in a very different learning environment. Shanker became a changed man.

Coincidentally, these were also the years that Ronald Reagan broke a strike of the Federal air traffic controllers union. Federal law denied them that right and Reagan fired them lock stock and barrel. Many historians consider this the beginning of the end for union power in America.

I was not sympathetic to the flight controllers. My parents were trying to get home from a European vacation when the strike marooned them in Europe.

No ally of unions, Reagan made common cause with Shanker who was preaching about something called “charter schools.” Everything Shanker said about them echoed my feelings as I taught in Duluth. Teachers should take a lead in moving to more effective education. Their chains should be cast off.

Al made an appearance in Duluth when I was teaching at Morgan Park 30 years ago. I was crushed that some other obligation prevented me from attending. After he left town the union newsletter took a shot at all the teachers who failed to appear. A threadbare audience must have embarrassed President Wanner, who was reduced to shaming his missing flock.

My teaching experiences were echoed on the front cover of a union teacher’s magazine. It showed a school floor plan without a roof. In each classroom was an isolated teacher. It suggested that there was a desperate lack of cooperation and coordination in our schools. I could relate. Teaching was a sink-or-swim business.

Not long afterwards I heard Shanker give a speech to the National Press Club. I wrote down a summary of his description of what it was like for a typical student to go through their hourly classes. This was the summary I jotted down:

Think of classrooms as workplaces, 25 coworkers doing a task for an hour then going on to somewhere else for an hour. They do this work by themselves at different rates of speed with varying levels of ability.

They sit still and keep quiet for hour after hour.

Their bosses embarrass them by asking them questions in front of their peers.

It is an annual organization, and the students are paid off once but not until the end of the year.

A lot of the work the kids do is uninteresting.

According to Shanker only about 10 percent of the students are getting the kind of education they should get, although he conceded that other experts put the figure as high as 35 percent.

The president of the nation’s fiercest teacher’s union wasn’t bragging about how great teachers were or complaining how underpaid, or overworked they were. Instead, he painted a picture of the nation that had been criminally negligent in educating all its children. For that, Shanker was a worthy hero.

Shanker was to rethink his advocacy of charters, especially in response to the Edison schools. He saw greedy Wall Street investors reaping billions of public tax dollars at the expense of teachers. That’s not quite how I saw it, but that’s another story.

Harry Welty recycles all his ideas at lincolndemocrat.com.