The ‘Ranown Cycle’ of Westerns

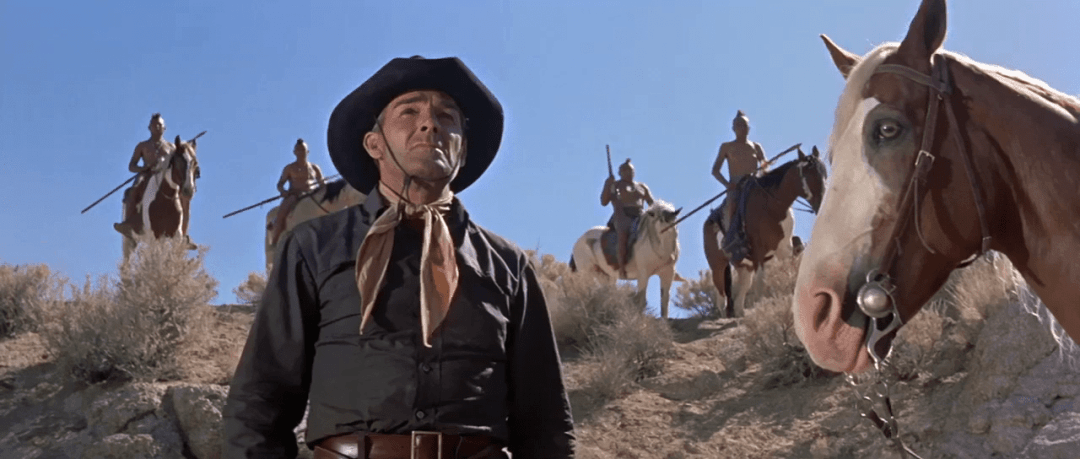

Randolph Scott in the last of the “Ranown Cycle” westerns, Comanche Station, 1960.

In a famous essay on the American Western movie published in The Partisan Review in 1954, Robert Warshow wrote: “It is an art form for connoisseurs, where the spectator derives his pleasure from the appreciation of minor variations within the working out of a pre-established order.”

That is certainly the case with the six Westerns in what is known as the “Ranown Cycle,” which fans have the opportunity to see in all their Technicolor, widescreen glory as a package on the Criterion Channel.

The Ranown Cycle refers to six westerns made between 1956 and 1960, starring Randolph Scott and directed by Budd Boetticher. Ranown was the name of Scott’s production company – the start of his first name combined with the last three letters of co-producer Harry Joe Brown’s last name.

Technically, the first movie in the cycle, Seven Men From Now, does not fit the brief because it was produced by John Wayne’s company Batjac. Wayne had commissioned the first-ever screenplay from for this film from Burt Kennedy, but when it came time to make the film, Wayne was cowboyed out after having just finished The Searchers for John Ford, so gave up the role to Scott, and, thereby, inadvertently opened the door to a great creative team.

Burt Kennedy continued to be a part of that creative team, writing all of the screenplays, although another writer was given the credit for Buchanan Rides Alone (1958) because, so the story goes, that writer’s wife was ill and he needed the money. Even though the writer’s script was deemed unusable and Kennedy was brought on to rewrite it, he relinquished credit to the original writer.

For Western fans, it was like striking a rich vein of ore when the Criterion Channel gathered all six of the Ranown Cycle westerns, along with a documentary made by Taylor Hackford about Boetticher talking mostly about his bullfighting days.

Randolph Scott has always been a favorite Western star of mine for his always solid and mostly noble characters. It wasn’t until his last film, Sam Peckinpah’s great 1962 Western Ride the High Country, that he got to play a rascal, and he did that well, too.

In the movies of the Ranown Cycle – Seven Men From Now (1956), The Tall T (1957), Decision at Sundown (1957), Buchanan Rides Alone (1958), Ride Lonesome (1959) and Comanche Station (1960) – Scott, always long and lean – is also now at his craggiest and most weathered.

Scott doesn’t seem to have to act much. He just is, a leathery part of the landscape. Little fazes his characters because they have seen it all. And he really seems to epitomize the Western hero Warshow wrote about in 1954: “his melancholy comes from the ’simple’ recognition that life is unavoidably serious, not from the disproportions of his own temperament. And his loneliness is organic, not imposed on him by his situation but belonging to him intimately and testifying to his completeness.”

Kennedy’s scriptwriting often begins in mystery, dropping us into a story that is already well underway, and we are left to wonder what is going on, until all is revealed in very short course. The longest of these six films is only 80 minutes (Buchanan Rides Alone) and the last two are tied for shortest at 73 minutes each.

Scott and Boetticher also made Westbound in 1959, but without Kennedy or Brown, so that must be why Criterion did not include it in this collection. Beotticher himself did not consider it part of the Ranown Cycle.

I’ve not seen Westbound, and I had seen only a couple of these films in the past, so now I know there is a common theme to them. Scott is almost always alone, and there is always something likeable about most of the protagonists in that they are just trying to make their way through a very harsh world.

The difference between Scott and the “bad guys” is that they sometimes are willing to take shortcuts, but only so much. They still have some ethics about how a man can live with himself.

That’s another thing that separates Boetticher from other Western filmmakers – the characters are not all black & white. There are shades of gray in good and bad characters. Several of the bad guys in these movies have ample opportunity to take Scott’s character out without a showdown. They might admit they could have killed him, but they also admit not being able to live with themselves had they done him like that. That’s highly unusual behavior for a film villain, but admirable here.

Take, for example, what appears to be a big breakout role for Lee Marvin in Seven Men from Now. He has great presence, and is particularly menacing without seeming to be so in an almost-claustrophobic scene in a wagon as he needles what he takes for a weak husband and declares his alpha maleness to the man’s wife, John Wayne’s friend Gail Russell, who just a few years after making this movie would be dead from alcoholism at the age of 36.

Russell made two films with Wayne (Angel and the Badman and Wake of the Red Witch, both in 1948) and in 1953 was accused by Wayne’s wife of being his mistress. The reason she might have starred in Seven Men from Now is that Wayne was originally to have had the lead role.

There’s not a lot of early exposition in these films. Boetticher and screenwriter Burt Kennedy drop you right in the thick of things.

Seven Men From Now begins on a dark and stormy night, with a lone character in silhouette – later we learn, Scott’s character, Ben Stride – riding in the night rain.

He comes upon two guys holed up in a cave with a fire and a pot of coffee. For all we know, he’s just getting out of the rain. Until the gunfire.

The men seem nervous as Stride joins them. A few words are exchanged that might not have much meaning for us, but are enough for Stride to shoot the two men to death.

And even then, we still don’t know the backstory, just that someone has been killed in the town of Silver Springs, where Scott’s character came from.

After dispatching the two cave men, the next scene is of a man and woman struggling to push their wagon out of a mudhole, until Scott rides along and quickly and efficiently pulls them from the mud. Since they’re all headed south, they team up for the ride.

Lee Marvin has his first big, meaty role as the bad guy who has certain ethical standards. But the theme throughout is that it takes a truer, more centered soul to be the hero. He’s not perfect. He’s got flaws. Pride is a big one. But he is fully aware of the flaws and prepared to exceed them when necessary.

It takes some time into the movie before we understand that Stride is hunting down the seven men who robbed a bank in his hometown and killed his wife during the holdup. At the same time, Lee Marvin’s character, Masters, is also following the bandits with the intention of keeping the stolen Wells Fargo money for himself.

The additional driving force to Stride’s singleminded pursuit is that the only reason his wife was working as a clerk in the place where she was killed is that he was too proud to accept the deputy sheriff position after losing the vote for sheriff. His wife was supporting them because of his wounded pride.

Once Stride accomplishes his mission, that leaves the showdown with Masters. It’s a beaut! One minute they’re facing off, and the next Masters is shot dead before clearing his holster, and Stride stands there with a smoking gun.

The next film, The Tall T, is based on an Elmore Leonard short story called “The Captives.” It has Scott’s character being ensnared in a ransom scheme by three bad guys led by Richard Boone. His confederates are the psychopathic Henry Silva who can’t wait to add to his kill count and a goofy Skip Homeier.

The woman held for ransom – the daughter of a copper baron – is played by Maureen O’Sullivan, and her character is supposed to be a very plain Jane who would have ended life as a spinster if some enterprising dude didn’t see the potential of marrying the daughter of the wealthiest man in the region.

It hadn’t been too many years before that O’Sullivan had played the very gorgeous and non-plain Jane to Johnny Weissmuller’s Tarzan in six films between 1932 and 1942.

Next is Decision at Sundown, which is sort of the weirdest of the bunch. Scott’s character is hunting the man he believed seduced his wife and made her commit suicide. He doesn’t learn until later that his wife was a tramp and the guy he’s hunting is just one of a crew of men she had flings with while married.

As the story develops, you gain respect for the supposed bad guy, played by John Carroll, who always seemed to me to be a B-movie version of Clark Gable. By the end of this film, he comes across as a somewhat likable guy that you really don’t want to be killed by Scott’s character.

In Buchanan Rides Alone, Scott’s character makes the mistake of entering a town controlled by one family.

The next film, Ride Lonesome, is also James Coburn’s film debut. Lee Van Cleef also has an early role, and Pernell Roberts is the good-bad guy in this one. He went directly from this to Ben Cartwright’s No. 1 son on Bonanza.

Finally, Comanche Station. Scott’s character lost his wife to Indians years ago, and now spends his time tracking down women who have been stolen by Indians. Unbeknownst to him, the latest woman he has freed has a bounty on her of $5,000, placed by her blind husband for her return, and three outlaws led by Claude Akins and including Skip Homeier again, want the reward for themselves.

Of course Scott prevails and returns the woman to her blind husband.

All of these films are beautifully shot, move quickly and surprise with very human characters.

In the Taylor Hackford documentary, Budd Boetticher: Study in Self-Determination, the director talks mostly about his bullfighting days – that’s what got him into movies in the first place, as a technical adviser on the 1941 Tyrone Powers bullfighting movie Blood and Sand – but he also discusses the Randolph Scott films and talks about the notion of “the sympathetic bad guy.”

“They were human,” he says.

Yes, I think that sums up what I love about the Ranown Cycle – the humanity of all

the characters.