Author’s love for Superior shines in new book of stories

Talking with Anthony Bukoski about writing, the word “romantic” comes up often. He understands the romance of writing, as well as the myth of the romance.

There is at first for the novice writer the romantic notion of the writer’s life. That must come with the inexplicable need to tell a story.

Of course, there is nothing at all romantic about the actual work of being alone in front of a blank sheet of paper or an empty screen with the task of creating something new that someone else would want to read.

Bukoski caught the writing bug early, growing up in a Polish-American community in the East End of Superior, Wisconsin – a place about as blue collar as it gets, and where most kids don’t aspire to a writing life.

“Oh, gee, it probably started in grade school, but I never accomplished much,” Bukoski said recently when we met in his beloved city. “I wrote naive stories. We had assignments, we had to write a story with some view in mind. I was under the influence of the television show, Tales of the South Pacific, or something like that, with Gardner McKay [it’s actually a very writerly series with the grand title James A. Michener’s Adventures in Paradise, featuring the aforementioned Gardner McKay as a Korean War vet who sailed to new adventures every week from 1959 to 1962 aboard his sloop Tiki III]. Of course, one of my stories was about a Tiki God. Sophomoric stuff.”

But there is no denying it was the romantic notion of writing about adventures on the high seas that got his creative juices flowing.

“And then I went in the Marine Corps, and when I was in Vietnam, I tried to write a play, but it was kind of stupid,” Bukoski said.

Still, he saw words as his way forward.

Upon discharge from the Marines, he returned to his hometown.

“When I got back, I thought, what else can I do but study English?”

Attending the University of Wisconsin-Superior, Bukoski quickly fell under the sway of poet and UWS English Professor George Gott, who taught there for 36 years and died in 2019 at the age of 93.

“I just liked the way he interpreted things and literature. I wanted to be like that,” Bukoski said, adding that he and Gott remained friends until the end.

Up to this point in his life, Bukoski disparages his writing. Does he recall when he cracked the code and understood how to tell a story?

“I sure do. Yeah,” he said with enthusiasm. “I had been trying for three years as an undergraduate at UW-Superior to write. I was so bad that I was the editor one year of the Cross Cut magazine, the literary magazine. I had submitted a story and it was so bad that it was refused. So I didn’t have an auspicious beginning by any means.”

He said it was another short story writer who showed him the way.

“I went to teach with my wife out east. We lived in Walpole, Massachusetts, and I was reading Flannery O’Connor, one of her short story collections. I came into the room one Sunday, late afternoon, where my wife was after working, and I said, ‘You know, I think I learned something about how to conclude a short story.’ And this was from reading Flannery O’Connor. The story was really clumsy. It was just terribly clumsy and naive. But I felt as though I had made a jump into the next level. I remember that distinctly.”

Well, once that leap was made, did it come easier?

“Oh, heavens, no. Harder. And I was, again, I’ll use the word naive, but it didn’t come easier. The writing was still naive, though, perhaps less so than it had been at UWS. But I kept trying,” he said.

He had his MA while teaching in Walpole and decided he wanted to go to grad school. He considered a number of schools, “But on a hunch, I tried the University of Iowa and submitted to them three stories for the Writers Workshop, and I don’t know how in the world I was accepted there, but I was. It was pretty strict getting in there and the stories weren’t at all good. But I got in. And from then on, I tried to mature.”

An important moment in his writing career happened in his second semester at the University of Iowa Writers Workshop. During Christmas vacation in Superior, he wrote a short story and submitted it to one of his instructors, novelist John Irving (The World According to Garp, etc.), who loved the story.

“And for someone who had no suc-cess, and no one noticed, we have John Irving actually dancing around when he was reading the story,” Bukoski said. “It made a big difference. I was determined never to quit. And here I am, 75-and-a-half years old and I’m really working hard. harder than ever. It’s not quite as easy to spend eight hours writing, but I’m eager to write, interested in it. And I think I’m improving.”

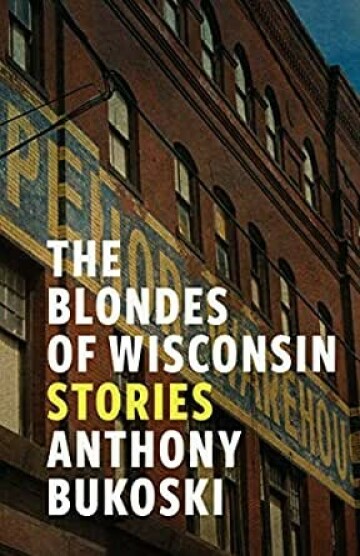

See what he means in his brilliant brand-new collection of short stories called The Blondes of Wisconsin, 16 stories that set a sense of place through character and situation unlike any short story writer I have read since Sherwood Anderson’s Winesburg, Ohio.

These are stories of haunted people – haunted by yearning, haunted by family, haunted by failure, haunted by past and future, haunted by their own lives, haunted even by success in a relationship.

They are also haunted by the ghosts of the city’s ethnic past, and eventually they all fade away and become, as one character says in the Christmas tale “A Dollar’s Worth,” “a mystery from a past. You cannot understand a ghost.”

The characters have a definite love for their Polishness, but some too have a grudge against their Polishness for how they are treated by others because they are Polish, whether it be in the homeland in 1939, as written about by emigre Polish author Bronislaw Slinker in the third story, “The Eve of the First,” or whether enduring Polish jokes from crewmates aboard the Great Lakes grain carrier Henry L. Stinson, as recurring character Eddie “Bronko” Bronkowski must do.

Eddie’s a great character. You come to know him quite well from different perspectives of people who love and know him. He’s a heavyweight boxer with a losing record, a palooka who’s taken too many punches and knows that one day he will lose his precious memories.

Bukoski’s interest in boxing is well represented by Eddie and in the title story about a traveling group of female boxers, one of whom resoundingly wins what sounds like Eddie’s last fight.

Two of the stories are credited as written by Bronislaw Slinker, a neighbor of the central family. Both have a very different tone from the rest of the stories, giving the illusion of actually having been written by someone else.

In one of those, “Who Is Bronislaw Slinker?” there is a line about being a Polish-American writer: “Because he’s a white ethnic writer, he’s pretty much voiceless in an America literature that praises certain ethnic groups while neglecting others.”

Talking with Bukoski, it’s soon apparent the above line is the author speaking directly to the reader.

“That’s true,” he said. “We’re not included in the multi-ethnic corpus. I’ve searched through many, many research books, some of them like 600 pages long. You don’t see Polish Americans referenced in the multi-ethnic books. You don’t see them in the anthologies of American literature. That’s fine. I’m trying to do what I can to celebrate us. But then sometimes, too often, I think what I write is not what people want to hear, you know. I can’t just write about how wonderful we are. We’re as violent, as mean spirited, ugly, and as beautiful and spiritual and artistic as people anywhere. I can’t just focus always on ancestor worship and grandeur, because it’s just not true.”

Beyond ethnicity, the other large presence in this collection is the City of Superior itself and its working-class seaport/railway heritage.

“I love this place. It is a magical place,” Bukoski said. “It’s all I knew and it really impressed me. And then later on the smell of the oil refinery, the lake wind, you know when things bloom, the train whistles and then the maritime commerce, the foreign vessels. I’m blessed, I guess. I’m rooted to place.

“And I’m blessed now because things still are the same. Much has changed, of course, but there are things that are the same.

“When I was a boy. I could hear the trains bring water up onto the dock and then going down the chutes. If the wind was right, you could hear that,” he said. “Well, now that dock is closed but they use it for fixing up vessels. The old dream of hearing ore freighters come in here, the order coming down, that’s gone. But the dreams, the idea of travel to exotic places, being on the edge of the wall, the long blue edge of Lake Superior The possibilities there. There’s a possibility for you to ship out.”

He agrees that when he was born matters. Had he been born just 10 years later, many of the cultural traditions of his Polish/Catholic heritage would have begun to disappear when he was growing up.

“Oh, heck yeah,” he said. “Even in terms of entertainment, even until 1957, I think we just had a radio. So I was blessed that way, because I had that radio listening, which helps the imagination, I think.”

Ultimately, Bukoski said he and Superior are inextricably woven together.

“I don’t know anything else,” he said. “But nothing else matters so much to me as the Superior East End. My wife and I’ve lived in great places. Louisiana, Lexington, Massachusetts, Concord. Just beautiful, beautiful towns. But no matter where I lived, I was I was desperate to be in Superior. I could never be happy anywhere but here. And I don’t know, I guess I just grew up from the land and the weather and the topography, the botany, all of those things, you know, have played on my sensibilities for a long, long time. I just want to write about them and the people here and celebrate our city and its people.”

Bukoski is also emeritus professor of English at UWS. His other books include:

Twelve Below Zero (1986, expanded edition 2008)

Children of Strangers: Stories (1993)

Polonaise: Stories (1999)

North of the Port (2008)

Time Between Trains (2011)

Head of the Lakes (2018)