A summer of neo-noir

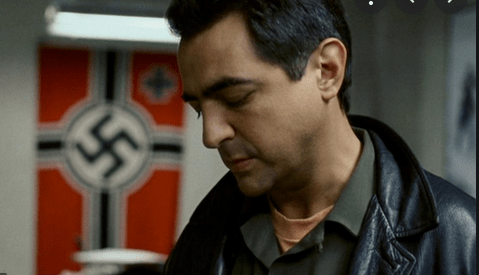

Joe Mantegna’s homicide cop riddled with Jewish guilt gets duped by conspiracy theories in David Mamet’s 1991 Homicide.

If noir is a state of mind, what is neo-noir?

Dip into the tasty new offering from the Criterion Channel to find out – a total of 26 films produced decades after the heyday of the genre, beginning with Cotton Comes to Harlem from 1970 and ending with Brick, 2005.

Sandwiched between them are an astonishing variety of tasty neo-noirs, many of which blew me way upon first viewing (I’ll highlight those as we go along):, Across 110th Street (1972); The Long Goodbye (1973); Chinatown (1974), Night Moves (1975); Farewell My Lovely (1975); The Killing of a Chinese Bookie (1976); The American Friend (1977); The Big Sleep (1978); Eyes of Laura Mars (1978); The Onion Field (1979); Body Heat (1981); Blow Out (1981); Cutter’s Way (1981); Blood Simple (1984); Body Double (1984); The Hit (1984); Trouble in Mind (1985); Manhunter (1986); Mona Lisa (1986); The Bedroom Window (1987); Homicide (1991); Swoon (1992); Suture (1993); The Last Seduction (1994).

Yes, many tasty morsels in there, with a few I’ve not seen and several I eagerly look forward to seeing again.

I start with David Mamet’s 1991 Homicide because I am surprised I have not seen it.

Reading Criterion’s description of the film, it sounds a bit more cerebral than I like my neo-noir. But I am a fan of Mamet’s word play, so let’s watch and see.

Joe Mantegna plays a New York city homicide detective with a penchant for losing his gun and who happens to be Jewish. His partner is played by a fresh-faced William H. Macy.

He becomes ensnarled in the murder of an old Jewish woman storekeeper because the woman’s wealthy family of, in Mantegna’s words, “high-strung Jews” want a Jewish cop to handle the case. And then he falls deeply into Jewish guilt. He goes in search of a major white supremacist conspiracy when in reality the old lady was killed by neighborhood kids who believed a long-held neighborhood rumor that she had a fortune in her basement.

Ving Rhames has a small role as Robert Randolph, a cop killer whose case Mantegna is pulled from to solve the old lady’s murder, which he never does.

Nice soundtrack by Alaric Janns, but not much more to say about this except not really my cup of neo-noir tea.

Let’s move on to Sutures, the 1993 feature debut of Scott McGehee and David Siegel. This comes to me from out of nowhere.

“How is it that we know who we are?” is the first line.

Then to a stark black and white faceoff between two gunmen.

The premise is that these two men are brothers of different mothers who have never met until their father’s funeral. They talk about how similar they look, yet one is played by white actor (Michael Harris) and the other is played by black actor (Dennis Haysbert, the voice of Allstate Insurance since 2003). They look absolutely nothing alike, so there is something surreal about their constant reference to their striking similarity.

White bro trades ID with black bro, then says he has to make a quick trip but will be back. In the meantime, he leaves black bro with a car and car phone, tells him not to forget the carphone. White bro calls black bro on the phone, apologizes, says he had no choice, pushes a button and blows up the car black bro is in.

But black bro survives, with amnesia and lots of facial damage.

He undergoes extensive facial reconstruction to match his ID, which is really that of his white bro Vincent. As he recovers and works with a psychiatrist on his memory, he is visited by Vincent’s mother, played by Dina Merrill. They are wealthy opera lovers, but Vincent has no visible means of support. And he is suspected of murdering his father, who had already been weakened by a stroke, and then shot in the head three times, most likely by his son. The cops think he did it, but then don’t know they’re staking out the true killer’s half-brother.

In a lineup with a woman who survives a shooting by whie Vincent, the woman says black Vincent bears a striking resemblance to her shooter but there’s something different in his eyes than what was in the eyes of the killer.

It’s all so bizarre I could not stop watching. But did I enjoy it? Well, again, not my cuppa neo-noir tea. Too modernist. Too neo, not enough noir. And way too much blah, blah, blah.

OK. Let’s start at the beginning with Cotton Comes to Harlem, which is based on his 1964 hardboiled crime novel of the same name, featuring two tough black detectives Gravedigger Jones and Coffin Ed Johnson, and written by Chester Himes, who was once described as “the black Raymond Chandler.”

Cotton Comes to Harlem is a light-hearted neo-noir romp based in hard racial truths of the period. It begins with a Back-to-Africa rally led by the charismatic Rev. Deke O’Malley, who roles up to the rally in a Rolls looking like a brother from another planet.

People of Harlem line up to surrender their money to O’Malley so they can leave their sordid lives of poverty behind.

Gunmen show up and steal the $87,000 collected from the people, and thus begins more of an exciting period piece than a neo-noir, but that’s OK.

There’s a bongo drum-driven car chase in early ‘70s style,complete with Keytone Koppish comic relief and lots of long-forgotten Motor City boats on the crowded city streets. Lots of nighttime street scenes. I want to go to FRANK’S CHOP HOUSE. For a mug of Rheingold.

Yeah, I don’t know if this does justice to Chester Himes’ novel. Been a while since I’ve read it, but seems to me there was a tad more gravitas to the story than Ossie Davis and crew have given it here.

Next up, Across 110th Street (1972). Now this is one of films I recall digging when I first saw it many years ago, partly because it’s an early starring role for Yaphet Kotto, one of my favorite actors of the 1970s, and for the theme song co-written by Bobby Womack and the great jazz trombonist J. J. Johnson, who also wrote the score.

The title refers to the street that separates Harlem from Central Park, sort of the unofficial boundary of race and class in the city at the time.

The film opens on a tense note when a mob bank is robbed by three black men posing as police officers, one of whom gets jumpy and shoots all the mob bankers with a machine gun.

Lots of cheap violence and manufactured racial tension between star and executive producer Anthony Quinn as a streetwise but racially insensitive cop near the end of his career and the up-and-coming straitlaced younger black cop played by Kotto.

Yes, it has not held up that well. Director Barry Shears cut his teeth on television, and much of this film today seems like it would be more at home as an overacted TV episode.

However, it should also be noted that as executive producer, Quinn did not want to play the role of the older cop. His first choice was John Wayne, then Kirk Douglas, then Burt Lancaster, but they all turned it down.

Quinn also wanted Sidney Poitier to play the role of the black cop, but apparently the Harlem community objected to that, saying the popular actor was not “street” enough to play the role, and so Kotto got it.

Again, you get a good look at New York City of the early 1970s in Across 110th Street.

My favorite thing in rewatching it was hearing J. J. Johnson’s exciting, percussive soundtrack moving things along.

It was also fun to see Anthony Franciosa as the mob boss’ son-in-law, acting as enforcer.

Here are some of the others that originally blew me away and that I look forward to seeing again. Will they live up to my expectations? We shall see.

Gene Hackman is the seminal isolated noir man in Night Moves (1975), directed by Arthur Penn. He plays Harry Moseby, an ex-pro football player now working as a private detective. I recall being highly impressed by this movie upon its original release.

James Woods made a major impression as a cop killer in the film version of Joseph Wambaugh’s The Onion Field (1979).

The thing I most remember about Body Heat (1981) is an actor who had a small but mesmerizing role as an incendiary expert. There was something about the way Mickey Rourke played that role – I knew I would see more of this guy. But overall, Lawrence Kasdan returns us to the overheated film noir days of the great Billy Wilder’s Double Indemnity here (perhaps the best of the genre).

“Murder has a sound all its own,” was the tagline for Brian DePalma’s stylish Blow Out (1981). John Travolta’s soundman trying to decipher sound clues of an assassination makes for brilliant cinema, and John Lithgow is an excellent evil bastard (which is why DePalma used him as such several times).

DePalma’s 1984 Body Double is this Hitchcock fancier’s most Hitchockian work, harking back to Vertigo, Rear Window and Psycho.

The Hit from 1984 is one of the couple of British neo-noirs in this collection, and I loved this story of world-weary hitman John Hurt and his apprentice Tim Roth on a trip to kill informer Terrence Stamp. Brilliant!

There is no denying that the Coen Brothers’ debut film Blood Simple (1984) is the best example of neo-noir ever made. Period!