A restorative justice dream for Duluth: Where truth and trust meet

The following speech was presented by Ted Lewis at the CJMM (Clayton Jackson McGhie Memorial) Day of Remembrance on June 15, 2021, at the request of the CJMM planning committee. The noon-hour event included other speeches and music that honored the 101-year anniversary of the 1920 lynching that took place at the intersection by the memorial site. Two days earlier, on June 13, Bryan Stevenson of the Equal Justice Initiative live-streamed his speech for a Twin Ports audience (postponed from the 2020 event). Stevenson is also the founder of the National Memorial for Peace and Justice in Birmingham, Alabama, also known as the National Lynching Memorial. Excerpts from his speech are in the following article.

We gather today in Duluth to honor the dead. But let us not forget that we honor these three young men for the nature of their death. We honor them because they were falsely accused and killed in the name of racism. Before they were lynched at this very intersection, they were stripped to the waist, undignified before the angry mob.

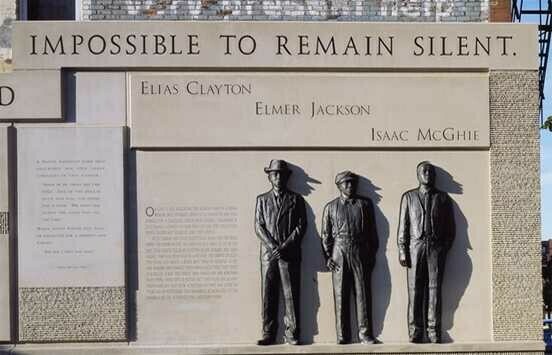

But that is not how we have memor-ialized these three men. We remember them in their dignity as human beings, fully clothed in their normal attire as represented in the bronze figures before us. Elias Clayton, Elmer Jackson, Isaac McGhie, not only dead, but resurrected in our community. Yes, resurrected, anastasis, literally in Greek, “to stand again.” They are standing tall before us, and thus they stand for all who have been unjustly treated and undignified, past, present, and future.

I hold in my hand a book about men and women who are serving life sentences for being convicted of murder charges. The book is full of their portraits. But they are not dressed as one might expect. Like Clayton, Jackson and McGhie, they are dressed in plain civilian clothes, dignified as if living productive lives outside the walls of prison. The photographer, Howard Zehr, a pioneer in the field of restorative justice, explains how “lifers often mature into thoughtful, responsible women and men who are remorseful for what they’ve done and who seek ways to contribute to society.” He mentions how most prison administrators will say how lifers, against all stereotypes, “are on the whole the most trustworthy and mature segment of the prison population.”

One of these lifers, a black man, is Commer Glass. He writes, “What’s most frightening about a life sent-ence is knowing I’ve acquired the capabilities and the knowledge to be somebody, to be a productive citizen, to be able to help others not get caught up in this situation – and (yet) not being able to really get out and help.”

Glass goes on to say, “I would like our society to take a good look at human beings and know that changes can be made by a lot of human beings who are doing life. There are a lot of good people sitting in these penitentiaries who are needed outside.” His comments put a whole new spin on “doing life.” You could say that “lifers” are not just doing time for the rest of their life; they are making time to give life to others.

A few years ago I had a chance to visit a group of men in a Michigan prison, all of whom were lifers for murder cases. I was there to describe my work as a restorative justice facilitator in a model that invites harming and harmed parties, after preparation meetings, to come together for healing dialogue. I told several stories from my casework.

When I opened up time for ques-tions, one question was dominant. “What can I do to help the families I victimized?” I told them the sad truth: “These very walls that lock in your supposed badness so it won’t touch people on the outside, are the same walls that lock in your goodness which could bring deep healing to people on the outside.”

And so I told them my dream, a dream where every offending and victimized person in our nation can have the chance to engage a restorative justice process, a process that brings life rather than death; a justice that does not primarily keep people apart, but brings them together; a restoration that weaves meaningful accountability with deep healing, allowing responsible parties to take positive response-ability to make things right, and allowing impacted parties to have a voice and have their emotional needs put to rest. Restorative justice is not only designed for criminal cases; well-facilitated, heart-felt dialogue can apply to any situation where people are divided by misunderstanding and mistrust.

Maybe some of you feel like you are serving a life sentence. Maybe you feel locked up by the unending flow of racist micro-aggressions you face daily. Maybe you feel locked up by trauma stemming from past harms, and you feel constrained by the challenge to navigate a society that brings unending reverberations of past hurts. Maybe you feel locked up because you simply want a steady job, wholesome work, and yet the mix of life circumstances and the lack of privileges resulting from our society’s hidden caste system make it difficult to climb out of that hole. These situations and more can feel like a life sentence, and one might rightly cry out, “How long, O Lord, how long?”

Many of us heard Bryan Stevenson’s deeply personal and moving speech yesterday. To reach a “just society,” he said, we have to first “get closer” to those who are marginalized, to those who are serving ‘life sentences’ on all levels of society but deserve something better. He talked about the “power of proximity.” To “get proximate” with others is to get near them. Near enough to listen; near enough to respond; near enough, he said, “to affirm the humanity and dignity of others.” Proximity is about people moving out of their defensive head-zone and into an open heart-zone. All of this is foundational to restorative justice.

Stevenson also said that proximity is not enough; there also has to be truth-telling. “Until we tell the truth,” he said, “we deny ourselves the beauty of what we call justice.” If true justice yields more life rather than more death, there is indeed a beauty in it. But this can only emerge when uncomfortable truths are named and understood. To reach the mountain top of reparation, both sides have to walk together through the valley of empathy. Restorative justice, to that end, does not simply hold space for safe conversation, but safe and brave conversation.

So the real challenge is…. How do you bring divided people together for hard conversations? How do mistrusting folk “get proximate” with each other? How, for example, can police officers come together for dialogue with community members affected by systemic harms?

Think of two Star Trek spaceships coming near each other: the USS Enterprise and a threatening Klingon ship. First thing that happens? Shields up! Both ships generate force fields of protection, generated by their internal enginery. We use our selective narratives by projecting the other’s otherness as a protective shield. What happens next? There’s communication. Captains appear on screens, talk to each other, size each other up. “Can I let my shields down?” they wonder. The only way there can be a two-way exchange and future co-existence is if trust rises from a debit zone into a credit zone. And that can only happen through communication.

Along with Stevenson’s matrix of truth and justice, I would like to add in one more element: trust. Without sufficient trust-building, truth-telling will not necessarily help divided groups to co-exist. In my work with harming and harmed people, they each need time to build up a credit of trust before they can meet for constructive dialogue. This includes three levels of trust: 1) trust in the facilitators, 2) trust in the container of the process, and 3) trust in their own truth-telling voice. Without enough trust in these areas, people do not feel it is worth the risk to come together for joint dialogue.

With sufficient trust, however, people will choose to move forward to meet with each other. That’s where the fourth and final level of trust-building happens: person to person. Human connections start to form. All of this takes time, and without enough trust, early truth-telling can sometimes backfire and cause more division.

I have a dream in Duluth that increasing numbers of people affected by harms large and small can safely and bravely “get proximate” with each other with the help of restorative facilitators.

I have a dream in Duluth that restorative dialogue processes can be available to all offending and victimized people who might not come together in each case, but can still meet with other conversation partners, such as surrogates.

I have a dream in Duluth that our youth can learn about restorative work upstream before they face conflicts and harms, and practice new skills for community-building and peacemaking.

I have a dream in Duluth that hard conversations about racism, as mentioned by Stevenson, can bring new groupings of people together for civic conversation and transformative action.

I have a dream in Duluth that police officers can safely yet bravely meet with community members, perhaps six on a side, where everyone, equally, can share stories of how they’ve been affected by violence, and thereby connect with each other.

Can you feel the kind of trust that gets reborn when people remove their shields of defense and have heart-to-heart conversation? It all starts with storytelling. Once people understand what others have experienced, and connect with the humanity of the other person, Shift Happens. Hear me right now: Shift Happens.

Over my years as a restorative practitioner, I’ve facilitated six cases involving police officers and civilians over grievance cases. I and another mediator would first meet with each party; a week later we would hold an hour long meeting with both parties. These were dignifying, confidential conversations that were strong enough for anything to be said as long as folks remained respectful. They all found resolution, resulting in no further disciplinary actions.

In three of these cases, I bore witness to officers making verbal apology to the citizens. “I’m sorry for how I handled the situation. I could have made better choices.” The result? Shift Happened. Tensions commonplace at the start of such meetings evaporated away. The citizen said, “Thank you.” At the end, everyone shook hands with a win-win outcome. If you want to strengthen community-police relations, that’s one good way to do it.

These days, we need to practice anything that unites us, and nothing unites divided groups better than storytelling. You can’t argue with a story; you can’t disagree with what others have experienced. Speaking and listening from the heart creates a relational bond. Once that bond is strong enough, conversations can go the next level to discuss structural changes for a better future.

In closing, we can honor the three men who stand before us by strengthening our moral imagination for restorative justice becoming normative rather than being peripheral. We can honor them by “getting proximate” with each other and with people across the divide. This means more communication processes, well-facilitated processes, processes that build bridges of trust strong enough to bear the weighty trucks of truth that can cross over to the other side.

I have a dream in Duluth that a new generation of facilitators can be trained to lead the hard but healing conversations that can make our community a place where every justice process yields new life. As Navajo Judge Robert Yazzie says, justice is not true justice unless, according to the Navajo word for “law,” beehaz’aanii, “life comes from it.” In this way we can join in full solidarity with our incarcerated sisters and brothers who are serving life, being ‘lifers’ with them in the best sense of the word, making life happen in the midst of making peace, thus making our world more just.

Ted Lewis is a restorative justice trainer and consultant for the Center for Restorative Justice & Peacemaking at the University of Minnesota, Duluth. He also serves on the executive committee for the National Association for Community and Restorative Justice. He lives in Duluth.