East avoided protocol, logic to oust Randolph

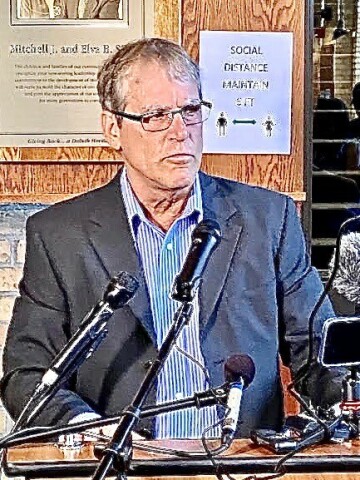

Mike Randolph appeared at an emotional press conference at Heritage Center to explain he was resigning for a lack of support after 32 years as Duluth East hockey coach. Photo by John Gilbert.

The tangled trail leading up to the elimination of Mike Randolph as Duluth East hockey coach led to widespread confusion, much of which has been caused by the board and by athletic director Shawn Roed and superintendent John Magas. They failed to disclose any evidence leading to the impasse with Randolph, who said he felt pressured to resign last week due to a lack of support from the school administration.

Magas, in a television interview, said he was “surprised” that Randolph submitted his resignation, but quickly added that honoring the resignation meant he and the board would not discuss Randolph’s departure, nor disclose results of the three-month investigation, which the board conducted, based on a complaint filed by a player who had quit the team because of a lack of ice time.

The “surprise” Magas mentioned was in itself a surprise, because Magas had failed to disclose that he was at the meeting when Randolph was told his contract would not be renewed, which obviously should have made his resignation a lot less surprising to those present.. That meeting included Randolph, Magas, members of the board, East principal Danette Seboe, Roed, Bruce Watkins, who is an interim human resources staffer, and Tim Sworsky, the investigator who had been hired to conduct the investigation.*

Repeated calls to Magas and Roed were not returned.

The news that his contract would not be renewed had to come as a jolt to Randolph, who cited a complete lack of support from anyone at the school as his incentive for resigning. He was weary, contemplating the same sort of fight he went through in 2003, when he lost his job for one season. Several school board members were voted off the board because of the decision to dismiss Randolph that time, and the new-look school board ordered Randolph reinstated as head coach the following year.

In that earlier case, assertions were made of discrepancies in the fund the East hockey team established by selling Christmas wreaths. No amounts were ever mentioned, which would have been embarrassing because there actually was a surplus from Randolph contributing profits from the summer development camps he ran for his players from August through September. He ran the camps five days a week with a game on Saturdays, for Squirts (age 9-10) from April through May, for Peewees (age 11-12) during June and July, and for Bantams (age 13-14) through August and September. After expenses for ice time and staff assisting him, he donated all profits to the fund, to facilitate using coach buses instead of school buses for the many scrimmage trips the Greyhounds made to the Twin Cities.

When he was accused of mismanaging the fund, Randolph turned it over to others and stopped donating his private camp profits. He also cut back on his camps, more recently operating with just Peewees and Bantams in June and July.

When Randolph took over the East program 33 years ago, it was far from the elite program people have since come to expect. East, Denfeld, Central and Morgan Park would routinely get trounced when paired up against the top four Iron Range teams in the first round of Region 7 playoffs. After Randolph took over, he started nurturing the various rinks in the East area, and the program rose to prominence, and started winning the sectional and advancing to the state tournament regularly.

To accomplish that, Randolph engineered a move out of the Lake Superior Conference, where games against Denfeld and Cloquet were the only real challenges, and he sought to replace the weaker opponents in the conference with an independent schedule against the best teams he could find anywhere in the state. He annually scheduled Edina, Hill-Murray, White Bear Lake, Minnetonka, Bloomington Jefferson, Burnsville, Moorhead, Grand Rapids, and, as they emerged in prominence, Eden Prairie, Elk River, Centennial, and Lakeville South and Lakeville North.

“Other teams had to stay and play all the teams in their conferences,” said Bob Gernander, who coached Greenway of Coleraine to two state titles in the late 1960s and watched Randolph turn East’s program into an elite power. “I’ve seen all the great coaches, like Larry Ross at International Falls, Oscar Almquist at Roseau, Cliff Thompson at Eveleth, Willard Ikola at Edina — and while I never like to say somebody is the best, I will say that nobody ever did more for their program than Mike Randolph has done for Duluth East.”

Randolph’s Greyhounds made it to 18 state tournaments, establishing an 18-3 record in section finals. His Hounds won two championships, finishing runner-up six other times, earning the third-place trophy five times, and the consolation title three times. That means in 18 trips to state, only twice did Randolph’s East team fail to come home with a trophy.

So, when superintendent Magas says the board will find an outstanding coach to take the program in a different direction, cynics might ask which direction might that be?

Coaches from other state powerhouse teams say that they admire the job Randolph has done to make East an elite team and keep the Hounds on top, and envy the winning culture they have. Randolph said letters and e-mails have poured in to offer support, although some have been apprehensive, because the Duluth School Board created the inference that Randolph did something so inexcusable that it couldn’t be divulged, along with the findings of the investigation into a player’s complaint.

Such damage to Randolph’s reputation may put the Duluth School Board, Magas and Roed into precarious positions, because during interviews with several returning players, some parents, and assistant coaches, the Reader has not found any such transgressions. Several players said it seemed the investigator only wanted to find negative comments. The school board’s investigation, in fact, raises questions about what protocol was followed to reach the conclusion that Randolph’s contract should not be renewed.

To trace the chronology, this past season’s East team was one of transition, with few experienced players but numerous strong but inexperienced freshmen and sophomores. That was not a recipe for success, and, coupled with the pandemic-delayed start to the season, East took its lumps from the strong opponents Randolph had lined up. When the season started January 4, Randolph conducted his blunt and direct player’s meetings, at which time he informed some marginal seniors who hadn’t previously played varsity that they may not play varsity in their final year, but were welcome to stay and play junior varsity, or go play Junior Gold, a youth level for Midget age players that would include seniors.

“I thought I was doing them a favor by not giving them false hopes,” Randolph said. “I think it’s important for kids to keep playing, if they love the game, and almost every year some kids who I’ve told that to have come back to be outstanding student managers for us.”

On January 21st, one senior delivered a lengthy letter to Randolph saying how he still loved the game but was quitting, implying Randolph hadn’t given him playing time with top linemates. That same letter appeared on social media that night, and the next day, January 22nd, Randolph received a call from Bruce Watkins, the interim HR staffer, saying they had received the same letter, and informing Randolph that an investigation would be organized to look into the departed player’s criticism.

The investigation consisted of interviews by a hired person with Randolph and some former players, as well as with many of the players from this past season’s team. Players interviewed by The Reader, meanwhile, said the interviewer focused on asking if the coach had used abusive language or any other questionable techniques. Various players said they never witnessed anything like that, when they said they only had positive experiences, the investigator cut the interviews short, causing them to suspect the interviewer was only trying to find negative answers. The Reader will not identify the players interviewed due to their age.

After the January incident, two other seniors who had been playing regularly on the third line got diminished ice time in a game because the fourth line outscored them. The two players in question had not registered a single goal or assist in all 11 games, despite regular play. They asked for a conversation with Randolph, to say they wanted to play more, and Randolph suggested if they played better they would get more ice time. The two players quit the team right then, and failed in an attempt to recruit other players to join them in quitting.

One sophomore said that the players he talked to were “at least 95 percent” in favor of Randolph returning, because they had learned a lot from playing on his team and were confident they could upset someone in the Section 7AA tournament. One said the team attitude was much improved and that “a cancer” had been removed from the team, leading to a brighter future.

After news of Randolph’s resignation spread through the team, parents of the returning players asked to meet with Randolph and implored him to tear up his resignation and reconsider. The players conducted their own meeting, and one representative went to Randolph’s house to tell him the players wanted him to reconsider and continue coaching. Randolph, surprised by the near unanimity of support within the team, said he would consider returning in the right circumstances.

In the week following Randolph’s resignation, Magas, Roed, the principal and some board officials met with the returning players, who asked questions about why their side hadn’t been heard from, since they are most affected, as returning players.. Some players said that the administration failed to directly answer their questions or gave only partial answers, mostly skirting the issues raised. Players also said Magas repeatedly said that because Randolph had resigned, they had to honor that decision and therefore wouldn’t discuss him, or the mysterious “findings” of the 3-month investigation.

The next day, parents of returning players were invited to the East auditorium for a similar meeting, and The Reader was invited to attend, too. Upon arrival, Magas politely informed The Reader representative and Ch. 10 sports director Chelsie Brown that they had decided the meeting would only be for “families,” and the media was not allowed to enter the auditorium. The parents, intending to get answers to questions about Randolph, were handed a list of rules for the meeting, concluding with one that said because it was Randolph’s decision to resign, they would honor that, and therefore no discussion of Randolph would be allowed.

Some of the parents came away from the meeting saying they realized that continuing to fight for Randolph might be futile, and a two players said they understood that attitude, perhaps by the board’s intimidating attempt to talk of “moving on in a new direction.”

Curious observers and athletic coaches of other schools may wonder how a complaint filed by a disgruntled player who quit the team in midseason could earn enough credibility from an entire school administration and school board, including a superintendent, who is in his first year after working in Green Bay, Wis. Such an apparent departure from protocol sets an alarming precedent for any coach, in any sport in the 709 School District, who has a player that quits, yet gains more support from an administration that offers no support for the coach.

* Correction: Athletic director Shawn Roed was not present at the meeting.