The family that plays together...

During the latter half of the 1960s, a great chasm existed for listeners of Top 40 AM radio (this is before FM hit Duluth). You had a mixture of middle of the road acts that appealed to an older crowd (Englebert Humperdink, for example), with rock acts who released singles from albums (The Doors, for example) and sugary pop acts that lived only for Top 40 hits.

It was the time of Steppenwolf vs. The Archies. Jimi Hendrix vs. The Cuff Links. King Crimson vs. the 1910 Fruitgum Company.

You chose sides. Rock or pop.

Rock always seemed more substantial, while pop seemed airy, wispy, replaceable with the next piece of bubblegum. Some of it was very catchy and inescapable, but a kid trying to build his rock credentials certaily doesn’t want to admit that he has teen idol Bobby Sherman’s 1969 single “Little Woman.”

I can honestly say that The Cowsills were never on my radar, which makes me wonder what made me tune into Family Band: The Cowsills Story, a documentary on Amazon Prime?

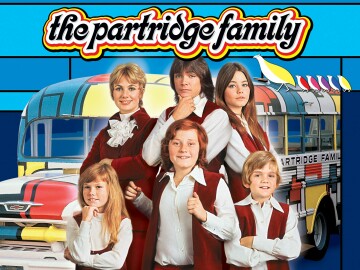

The fact that The Cowsils were the inspiration for The Partridge Family – yes, Mrs. Cowsill was in the band with her children – had nothing to do with the decision to watch because The Partridge Family was never cool enough for me to watch, so there is no connection there.

Much later – in the late 1990s – I was a fan of the band Continental Drifters, which Susan Cowsill was a member of, along with Peter Holsapple of the dBs and Vicki Peterson of The Bangles (who is married to John Cowsill, who drums for The Beach Boys). But the Continental Drifters were not even mentioned in the documentary – only that Susan continued to play music – and I wasn’t looking for that from this anyway.

Basically, this is the story of a group of talented kids brimming with music and ambition, only to be sabotaged by the mismanagement of their abusive, alcoholic father. We learn Bud Cowsill’s abuse was all consuming – mental, physical and spiritual – and that he effectively killed what looked like an unstoppable career for his talented family.

In the beginning, the Cowsills say in this documentary, Bud Cowsill was extremely supportive of the band and would beat on doors to get them noticed. Unfortunately, they say, he never stopped beating on doors, even when The Cowsills were the flavor of the moment, appearing on every variety show imaginable.

Here is just one example of the many deals Bud Cowsill fudged up with his behavior. The biggest show in the world at the time was Ed Sullivan’s Sunday night variety show. That’s where The Beatles made their American debut. Sullivan was so taken with The Cowsills that they were signed to do an unprecedented 10 Sullivan appearances, but after only two, they were not asked back. Dad had annoyed someone enough to get his kids banned from Sullivan’s show.

The same was true with a sitcom that had been planned for the family. Dad scotched the deal.

Over and over, the senior Cowsill alienated others in the music and entertainment business to the point where nobody wanted to work with The Cowsills. In four years of hits and endless performances and TV appearances, The Cowsills earned an estimated $20 million, all of it squandered by their father. No one seems to know what he did with all the money the family band earned. The kids tell stories about when they became adults, they found they owed taxes on money they never saw.

The band began in 1965 in the Cowsills’ hometown of Newport, Rhode Island, with older brothers Bill and Bob on guitars. Younger brother Barry soon joined on drums, but then moved to bass and was replaced on drums by John. The quartet soon expanded to include siblings Paul and Susan, as well as mother Barbara. Paul, we learn, was added to the group because his older brother Richard, Bob’s twin, terrorized Paul when they were left home alone when the family was on the road.

At one point the kids tried to get Richard into the band playing drums. Bob said he had much more power than younger brother John. But Bud – who reportedly didn’t like his son Richard –said Richard couldn’t play drums in the band. He told him to join the military.

“What he said went,” Richard said. “If you didn’t do what he said, KA-BAM. It got physical.”

Richard joined the military and was sent to Vietnam, where he became a heroin addict.

The band began as a foursome of brothers – Billy, Bob, Barry and John – playing at local dances and frat parties. They got a record contract, but didn’t have a hit until they were signed by Mercury and began working with producer Artie Kornfeld, one of the principal promoters of the Woodstock concert).

Koprnfeld said he immediatley heard the potential of the brothers.

“They were incredibly talented, monsters right out of the chute,” he said, describing them as “the pre-Osmond Osmond Brothers.”

Kornfeld and another sngwriter came up with a song called “The Rain, The Park & Other Things” for the boys. It played on the flower child theme of the time – “I love the flower girl.”

It’s a lovely little slice of gentle, hippyish folk pop of the times, and at the time it reached No. 2. It was kept out of the No. 1 spot by The Monkees’ “Daydream Believer.”

“Just like that, we had a hit record,” Kornfeld said.

It seems Bud Cowsill began exerting influence on his son’s band just after that first hit. That’s when Mom, Barbara Cowsill, joined her son’s band.

“We love our Mom, but we challenge you to find a teenage boy anywhere who wants his Mom in his rock band,” said Bob Cowsill. “Dad had a master plan. It wasn’t long before little sister Susan was added.”

Susan gives an aside, saying she knew her brothers didn’t want their “creepy little sister” in the band, but she took her place, singing harmonies with her mother and frugging away on stage.

Two musicians close to The Cowsills during their prime recall the tumultuous home situation they existed in.

Guitarist/producer Waddy Wachtel was a friend of Billy Cowsill and was workign with the band.

“The atmosphere in their home was a tinder box waiting to erupt, volatile,” he said. “Great kids. Mom was a wderful lady.but they were all walkign on eggshells in that house because al you’d do is look at him the wrong way.”

Tommy James of the band Tommy James & The Shondells said some of the boys would hide out at his apartment when their dad was on the warpath.

“I was very aware of what was going on in the family,” James said. “The father was very dominant. Every now and then he’d get real dominant, I guess if we was drinking.”

“The one thing we had that could not hurt us was music,” Bob Cowsill says. “We were busy and we were famous. We were really having a lot of fun.”

Then Bud fired producer Kornfeld, so the older boys began producing the band.

But the family started to notice things fall apart. They were offered a summer replacement spot for Carol Burnett’s variety show, but that dried up. There was also talk of a sitcom starring the family, but that also never happened.

Bob said the family soon learned that because of their father’s volatile nature, “people only wanted to deal with us once.”

Bud came to the band with what he said would be their next song, a piece called “Indian Lake” that was so bad it caused oldest brother Billy, 19, to cry with frustration. His Dad smacked him for crying. And then Bill went to work on it.

“I whipped it into some kind of popness and rock ‘n’ roll as I could with this piece of shit material. And it was our next single. And it only hit 800,000. It didn’t hit a million. And that’s when the politics of my father and myself started breaking down rapidly.”

The final rift between the two was coming, but in the meantime, the boys accidentally produced their next single and biggest hit – “Hair,” from the musical of the same name.

Carl Reiner was producing a TV special called The Wonderful World of Pizzazz, a look at fashion and style trends around the world, with musical guests The Cowsills and Harper’s Bizarre.

Reiner that it would be great for The Cowsills to shed their family image on the show by donning Japanese wigs and lyp-synching to the song “Hari.”

Bill tells the story that he and Bob went into an 8-track recording studio and cut a truly sonically amazing record.

They told MGM it was going to be their next single.

“They said Bullshit!” Billy said. “They thought this was just outrageous.”

But the band was being interviewed by a DJ at WLS in Chicago. They brought along an acetate of “Hair” and bet the program director he could not name the band. When he could not do so, he played the record on air and dared listeners to name the band. They could not guess either, but suddenly requests came pouring in for the song.

“There were so many requests for it that MGM had to go and print the next day,” Billy said. “That song sold 2 millon, 500,000 records.”

Shortly after producing the band’s biggest hit, Billy was fired from both the band and his own family, a move that all surviving Cowsills say was the worst thing their father ever did.

Now Bob had to step up.

“Bill was our voice,” Bob said. “Bill Cowsill was The Cowsills’ Brian Wilson. It was the absolute beginning of the end.”

“We continued on as a broken wagon,” John Cowsill added.

After Bill left, the group left MGM.

“We still were doing OK,” Bob said. “We were making records that weren’t going anywhere. They were good but they weren’t up to snuff.”

Ultimately the industry was more interested in the image of the band rather than it’s music, and then tastes changed and that image easily faded..

The documentary seems to be driven by Bob Cowsill’s need to understand what happened with a band that was on top of the world one minute, and the next, nothing.

“When it all shattered, we all scattered,” Bob said.

The story then takes a sad turn as we learn that Barry Cowsill died in New Orleans in the aftermath of Hurricane Katrina, and big brother Bill died on the very same day.

The remaining Cowsills continue to perform. This documentary has made me want to add some Cowsills to my record collection.