What can happen when good people become complicit with their oppressors

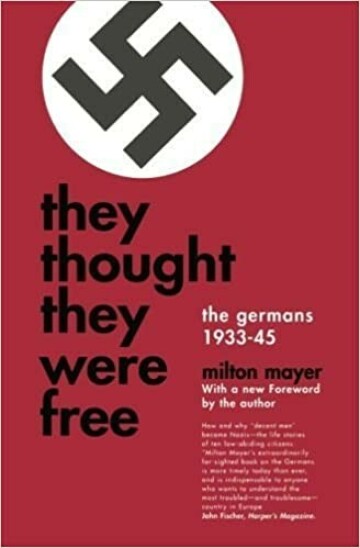

Excerpts from Milton Mayer’s They Thought They Were Free: The Germans, 1933-45 – Quotes from Germans that were Cunningly Led by the Nazis to Participate in the “Final Solution”:

“If the last and worst act of the whole regime had come immediately after the first and smallest, thousands, yes, millions would have been sufficiently shocked – if, let us say, the gassing of the Jews in ’43 had come immediately after the ‘German Firm’ stickers on the windows of non-Jewish shops in ’33.”

“Suddenly it all comes down, all at once. You see what you are, what you have done, or, more accurately, what you haven’t done (for that was all that was required of most of us: that we do nothing).”

“What no one seemed to notice was the ever-widening gap, after 1933, between the government and the people. You know, it doesn’t make people close to their government to be told that this is a people’s government, a true democracy.

“What happened here was the gradual habituation of the people to being governed by surprise; to receiving (conspiratorial) decisions deliberated in secret; to believing that the situation was so complicated that the government (and their bureaucrats) had to act on information which the people could not understand, or was so dangerous that, even if the people could understand it, it could not be released because of ‘national security.’

“This separation of government from people, this widening of the gap, took place so gradually and so insensibly, each step disguised (perhaps not even intentionally) as a temporary emergency measure or associated with true patriotic allegiance or with real social purposes. And all the crises and reforms so occupied the people that they did not see the slow-motion underneath, of the whole process of government growing remoter and remoter.

No one had time to think

“The dictatorship, and the whole process of its coming into being, was, above all, diverting. It provided an excuse not to think for people who did not want to think anyway. Most of us did not want to think about fundamental things, and we never had. Nazism gave us some dreadful, fundamental things to think about. We were decent people—and the fascists kept us so busy with continuous changes and ‘crises’ and ‘national enemies’ without and within, that we had no time to think about these dreadful things that were growing, little by little, all around us.

“To live in this process is absolutely not to be able to notice it unless one has a much greater degree of political awareness than most of us had ever had occasion to develop. Each step was so small, so inconsequential, so well explained or, on occasion, ‘regretted,’ that, unless one were detached from the whole process from the beginning, one no more saw it developing from day to day than a farmer in his field sees the corn growing. One day it is over his head.

“How is this to be avoided, among ordinary men, even highly educated ordinary men? Many, many times since it all happened I have pondered that pair of great maxims, ‘Principiis obsta and Finem respice’ – ‘Resist the beginnings’ and ‘Consider the end.’ But one must foresee the end in order to resist, or even see, the beginnings. One must foresee the end clearly and certainly. How is this to be done even by extraordinary men?

Act before it’s too late

“Your ‘little men,’ your Nazi friends, were not against National Socialism in principle. Men like me, who were the greater offenders, not because we knew better but because we sensed better. Pastor Niemöller spoke for the thousands and thousands of men like me when he spoke and said that, when the Nazis attacked the Communists, he was a little uneasy, but, after all, he was not a Communist, and so he did nothing; and then they attacked the Socialists, and he was a little uneasier, but, still, he was not a Socialist, and he did nothing; and then the schools, the press, the Jews, and so on, and he was always uneasier, but still he did nothing. And then they attacked the Church, and he was a Churchman, and he did something—but then it was too late.”

“…one doesn’t see exactly where or how to move. Each act, each occasion, is worse than the last, but only a little worse. You wait for the next and the next. You wait for one great shocking occasion, thinking that others, when such a shock comes, will join with you in resisting somehow. You don’t want to act, or even talk, alone; you don’t want to go out of your way to make trouble; you are not in the habit of doing that.

“Outside, in the streets, ‘everyone’ is happy. One hears no protest, and certainly sees none. In France or Italy there would be slogans against the government painted on walls and fences. In the university community, in your own community, you speak privately to your colleagues, some of whom certainly feel as you do; but what do they say? They say, ‘It’s not so bad’ or ‘You’re seeing things’ or ‘You’re an alarmist.’ (Or you’re a conspiracy theorist.)

“And you are an alarmist. You are saying that this must lead to this, but you can’t prove it. These are the beginnings, yes; but how do you know for sure when you don’t know the end? On the one hand, your enemies, the law, the regime, the Party, intimidate you. On the other, your colleagues pooh-pooh you as pessimistic or even neurotic. You are left with your close friends.

“But your friends are fewer now. Some have drifted off somewhere or submerged themselves in their work. You no longer see as many as you did at meetings or gatherings. Informal groups become smaller; attendance drops off and the organizations themselves wither. Now, in small gatherings of your oldest friends, you feel that you are talking to yourselves, that you are isolated from the reality of things. This weakens your confidence still further and serves as a further deterrent. It is clearer all the time that, if you are going to do anything, you must make an occasion to do it, and then you are obviously a troublemaker. So, you wait, and you wait.

“But the one great shocking occasion, when tens or hundreds or thousands will join with you, never comes. That’s the difficulty. If the last and worst act of the whole regime had come immediately after the first and smallest, thousands, yes, millions would have been sufficiently shocked—if, let us say, the gassing of the Jews in ’43 had come immediately after the ‘German Firm’ stickers on the windows of non-Jewish shops in ’33.

“But of course this isn’t the way it happens. In between come all the hundreds of little steps, some of them imperceptible, each of them preparing you not to be shocked by the next. Step C is not so much worse than Step B, and, if you did not make a stand at Step B, why should you at Step C? And so on to Step D.

“And one day, too late, your prin-ciples, if you were ever sensible of them, all rush in upon you. The burden of self-deception has grown too heavy, and some minor incident, in my case my little boy, hardly more than a baby, saying ‘Jewish swine,’ collapses it all at once, and you see that everything has changed and changed completely under your nose. The world you live in—your nation, your people—is not the world you were born in at all. Now you live in a world of hate and fear, and the people who hate and fear do not even know it themselves. When everyone is transformed, no one is transformed. Now you live in a system that rules without responsibility.

”You have accepted things you would not have accepted five years ago, a year ago, things that your father, even in Germany, could not have imagined.

All that was required of us was that we did nothing

“Suddenly it all comes down, all at once. You see what you are, what you have done, or, more accurately, what you haven’t done (for that was all that was required of most of us: that we do nothing). You remember those early meetings of your department in the university when, if one had stood, others would have stood, but no one stood. You remember everything now, and your heart breaks. Too late. You are compromised beyond repair.

“Once the war began resistance, protest, criticism, complaint, all carried with them a multiplied likelihood of the greatest punishment. Mere lack of enthusiasm, or failure to show it in public, was ‘defeatism.’ You assumed that there were lists of those who would be ‘dealt with’ later, after the victory. Goebbels was very clever here, too. He continually promised a ‘victory orgy’ to ‘take care of’ those who thought that their ‘treasonable attitude’ had escaped notice.