Dorothy Arzner’s Hollywood

Lucille Ball confides in Ferdinnd the Bull in Dorothy Arzner’s 1940 film Dance, Girl, Dance.

Who could pass up this movie description: “A drunken newspaper man is rescued from his alcoholic haze by an heiress whose love sobers him up and encourages him to to writer a play, but he lapses back into dipsomania.”

The dipsomaniac is played by Frederic March, and the movie title is his favorite toast – Merrily We Go to Hell.

I stumbled upon this film as I searched for a new and exciting movie on one of my streaming channels. The problem is that my preferred genre is what today is typically dismissed as “classic” film, i.e., old black and white movies, preferably pre-1955.

Just as I was beginning to feel I had seen it all, a title caught my eye – Merrily We Go to Hell.

The title alone tells me this is a pre-code movie – which means it was made before the 1934 Motion Picture Production Code.

This one is from 1932 and stars March and Sylvia Sidney. March, the a drunken newspaperman/would-be playwright who marries wealthy socialite Sidney. Much drunkenness and adultery ensues.

Merrily We Go to Hell is by a director I am amazed to learn I have never heard of before the moment I found this film. Her name is Dorothy Arzner, and during her 20-year, 16-feature film Hollywood career, she was the only female member of the Directors Guild of America.

After being introduced to her, I have not stopped hearing about her either through reading or random references – her name was even mentioned recently in an NPR story.

She started her Hollywood career in 1919, typing scripts for the Famous Players-Lasky Corp., which a few years later became Paramount Pictures. After six months of typing scripts, she became a film cutter/editor at a Paramount subsidiary, cutting and editing 52 films before being called back to Paramount in 1922 to edit her first major motion picture – the Rudolph Valentino vehicle Blood and Sand. She also directed – uncredited – some of the bullfighting scenes.

Arzner worked on several more Paramount pictures before leaving to write scripts for independent production companies. By 1926 she was back at Paramount, editing the film from her own script, The Red Kimono.

Dorothy Arzner

After the successful release of The Red Kimono, rival studio Columbia offered Arzner a job as writer and director, but it was a “B” picture, and Paramount countered by offering to let her direct an “A” picture.

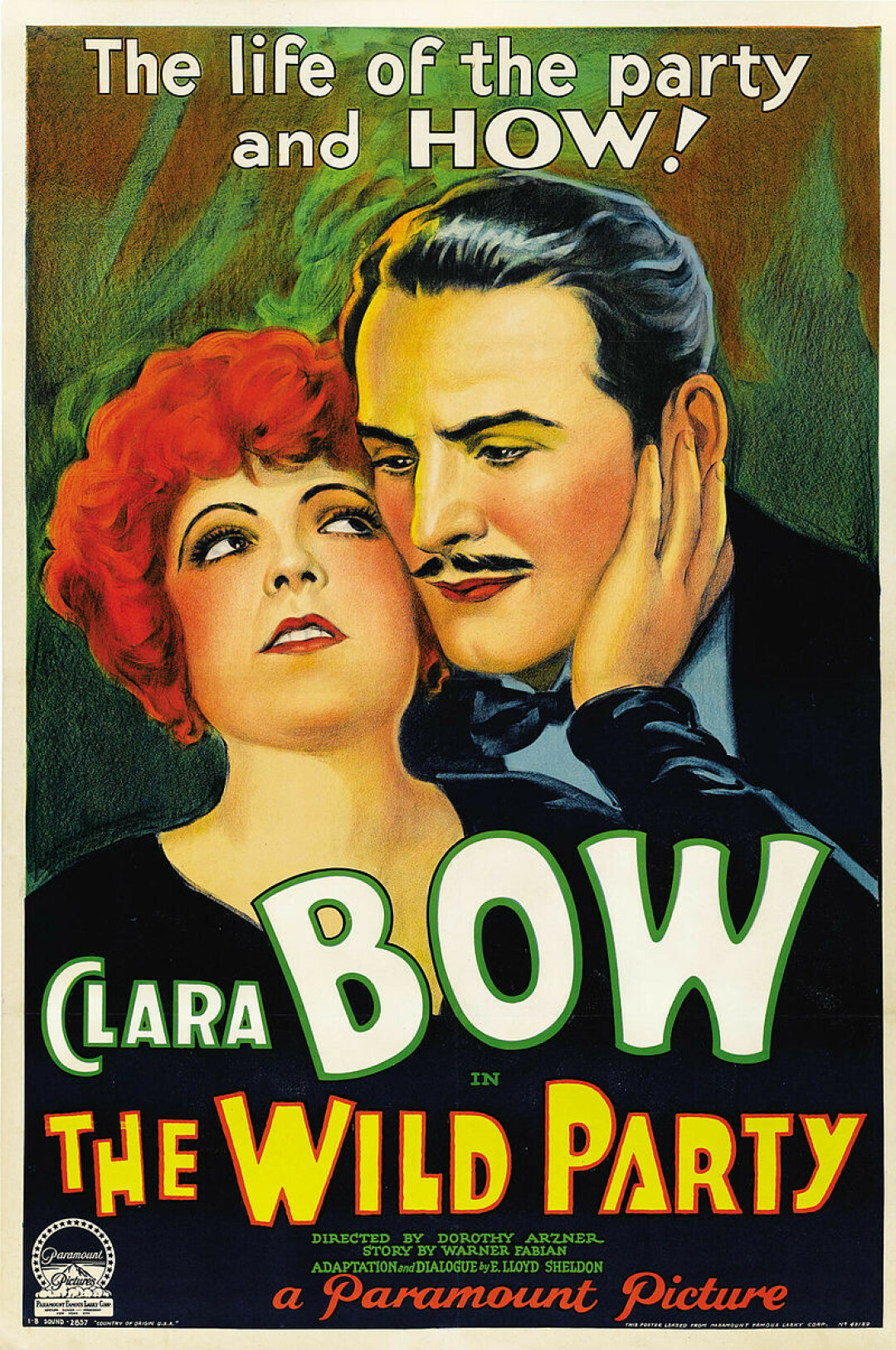

After directing four successful silents for Paramount – Fashions for Women (1927), Ten Modern Commandments (1927), Get Your Man (1927) and Manhattan Cocktail (1928) – she was entrusted with directing Paramount’s first sound film, The Wild Party, starring “It” girl Clara Bow. It also marked the film debut of Racine, Wisconsin-born Fredric March, who would eventually be cast in three more Arzner films.

It was during the making of The Wild Party that Arzner used a fishing pole to invent the boom mike. While she is credited with the invention by necessity, she did not take out a patent, but someone at a rival studio did, not long after she introduced the innovation.

Arzner went on to direct Katharine Hepburn in her first starring role, Christopher Strong (1933), Rosalind Russell in Craig’s Wife (1936), Joan Crawford in The Bride Wore Red (1937) and The Last of Mrs. Cheyney (1937), and both Lucille Ball and Maureen O’Hara in her best-known film, Dance, Girl, Dance (1940).

So far Dance, Girl, Dance is the only other Arzner film I’ve been able to get my hands on. Arzner’s editor on this film was a young man by the name of Robert Wise, whose next editing job would be a little thing called Citizen Kane. He would go on to direct some of the great American movies of the 20th century.

Dance, Girl, Dance is a very strange movie about ballet and burlesque dancers. Maria Ouspenskaya, who would play her most memorable role the following year as the gypsy woman in The Wolf Man, plays a short but memorable role early in the movie as a butch dance teacher. When we first meet her, her hair is pulled back tightly and she is wearing a shirt, tie and suit coat – looking very much like an older version of Arzner.

Arzner was a lesbian and, so, there naturally are claims of lesbian themes in her films. Her longtime companion, choreographer Marion Morgan, worked as choreographer on Dance, Girl, Dance.

Dance, Girl, Dance was a critical failure upon its release, but today it is seen as a rare example of empowered women from that period. In 2002 it was named one of the Top 100 Essential Films by the National Society of Film Critics.

Katharine Hepburn in Arzner’s Christopher Strong.

One sense of empowerment comes when reluctant burlesque dancer/hopeful ballerina Maureen O’Hara stops her routine to berate the male audience for paying “50 cents for the privilege of staring at a girl the way your wives won’t let you…with your silly smirks that your mothers would be ashamed of…so you can go home when the show’s over and strut before your wives and sweethearts and play at being the stronger sex for a minute. I’m sure they see through you just like we do.”

Her monologue causes an ovation, which irritates the gold-digging star of the show, Lucille Ball, who says, “Trying to steal my show, you jealous little pig,” before slapping her. A fight ensues and they end up in night court with a sympathetic judge who proves that not all men are pigs.

Arzner’s final feature film was a war drama called First Comes Courage (1943), starring Merle Oberon.

Although she lived another 36 years, dying at age 82 in 1979, Arzner never made another feature film.

She went on to make training films for the Women’s Army Corps, produced a radio program, taught filmmaking at UCLA for four years in the 1960s, and made a series of more than 50 Pepsi commercials at the request of her old friend Joan Crawford, who married the head of Pepsi in 1955.

Arzner’s disappearance from feature filmmaking remains a mystery, although there is speculation that Hollywood homophobia reached its pinnacle in the post-war years and drove her away.

In a 1974 interview, Arzner said no one gave her trouble as a woman director, but added, “Men were more helpful than women.” Also in that interview Arzner said she left Hollywood and filmmaking on her own terms because she simply had enough of Hollywood.

The same year as Arzner’s final film, 1943, a 25-year-old British-born actress was awarded the New York Film Critics Award for Best Actress for her role in the musical The Hard Way. Six years later, Ida Lupino would direct her first film. More on her next week.

Arzner had the honor of directing Paramount’s first sound film, The Wild Party.