Streaming all that jazz

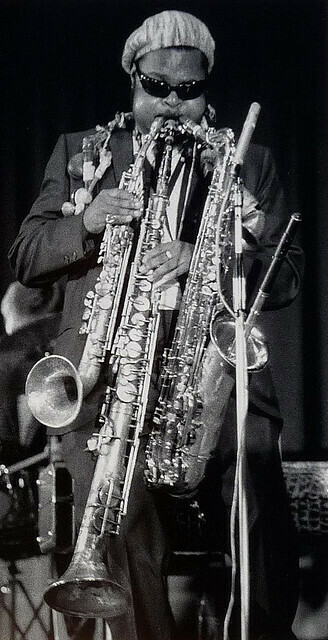

Roland Kirk

Roland Kirk

I’ve forgotten the exact year it happened, sometime earlier in this century I cut the cable and have been a dedicated streamer ever since. Being a devoted streamer, I’m not just sitting around waiting for Part 3 of Making of a Murderer or the next Tiger King. Yes, I do series binging when I find a weird and wonderful series, and they are out there, but sometimes it takes deep diving to find the gems among the dreck, and there are mountains of dreck available.

Whatever musical genre you care to explore, you’ll find some great documentaries available for streaming, however, I thought I’d kick off this new column by looking at a few of the great jazz documentaries you can stream.

I have to start with one of my favorite jazz cats – the one-man reed Rahsaan Roland Kirk. First time I heard of him was when Eric Burdon sang about him on the fabulous 1970 album Eric Burdon Declares War, which opens with the Burdon-penned two-part song called “The Vision of Rassan (sic)”:

“But can you dig on his name now?

I said it’s Roland Kirk.

Make them work, Make them work, Roland Kirk yea.”

And that was all I knew about Rahsaan Roland Kirk until two years later when Kirk and his band, the Vibration Society, appeared on an hour-long PBS show, and I witnessed the phenomenon of this seemingly joyous blind musician playing multiple horns at the same time.

I became a fan and buried in a box somewhere are a couple of jazz magazines with Kirk cover stories, including one done after he suffered a stroke in 1975 that paralyzed his right side, but he relearned how to play with one working arm.

I recall seeing him interviewed post-stroke, and somehow he and the interviewer got on the topic of death. Kirk said when he died, he wanted to be cremated and then he wanted his friends to put his ashes in a hash pike and smoke him. I thought that was hilarious, and it endeared Kirk to me even more. He died after a second stroke in 1977 at the age of 41.

His story is told in the 2014 documentary The Case of the Three-Sided Dream.

Kirk was seen by many as a gimmicky sideshow freak, but friends and fellow musicians say those who said that were not really hearing what Kirk was doing, or as one says, “He knew the power of sound, the physics of sound….sound was his life.”

The idea of playing multiple horns at once came to him in a dream, and as his wife, Dorthann Kirk says, “His religion was the religion of dreams. I never asked him what that meant.”

There’s a great segment when Kirk was invited to perform on America’s longest-running variety show, The Ed Sullivan Show. He was scheduled to perform his version of Stevie Wonder’s hit “Ma Cherie Amour” (which appears on Kirk’s 1969 album Volunteered Slavery). Instead, he assembled an all-star band that included Archie Shepp on sax, Roy Haynes on drums and Charles Mingus on bass and decided to play “true black music.” He chose to send to every home in America with Ed Sullivan on the tube a rousing version of Mingus’ “Haitian Fight Song.”

One segment in particular reveals the essence of Kirk. During an amazing live performance Kirk is simultaneously playing that old apple pie melody “Sentimental Journey” on one horn and Dvorak’s New World Symphony on another. Kirk often liked to talk to his audiences, and he mentions that some people say Dvorak was black but the white people say he was white.

“But what do you say?” a man in the audience calls out.

“I say I don’t give a damn,” Kirk says and laughs heartily.

***

Talmage Farlow

Talmage Farlow

Guitar fans need to check out Talmage Farlow, a 1981 documentary about the great jazz guitarist better known as Tal Farlow, and whose own humility may have kept him from becoming a bigger name to anyone but jazz diehards.

Farlow first came to prominence in 1949 as a purveyor of West Coast cool jazz in the Red Norvo Trio, with vibraphonist Norvo and Charles Mingus on bass. He left the trio in 1953 and joined Artie Shaw in the Gramercy Five before returning to the trio format two years later.

And then in 1958, Tal Farlow and his beautiful Gibson sort of dropped out of the scene. While he took the occasional club date, many people thought he retired.

“There’s no such thing as retiring in music,” Farlow’s old bandmate Red Norvo says, explaining that while Farlow may only be making music in his home studio, he’s still making music.

Other than contemporaries interviewed for the documentary, George Benson, who was one of the big names in jazz guitar when this documentary was made, said it would never enter another guitarist’s mind to try to “cut” Tal Farlow. “Forget it!” Benson says.

Benson then tells a gruesome story his father told him about men who would have the webbing between their fingers operated on so they would have a bigger reach on the guitar neck, but Farlow’s gigantic hands make a plaything out of a guitar neck. You get a chance to see just how large his hands are when fellow guitarist Lenny Breau’s hand is dwarfed by Farlow’s.

There are a couple of scenes where Farlow is playing and he looks like a mad scientist, hovering above his Gibson as he picks and plucks and taps out magical sounds.

The documentary ends with Farlow giving a concert. He did more after this documentary was originally released in 1981 and people discovered this massively talented guitarist still had the magic. Farlow died in 1998 at the age of 77.

***

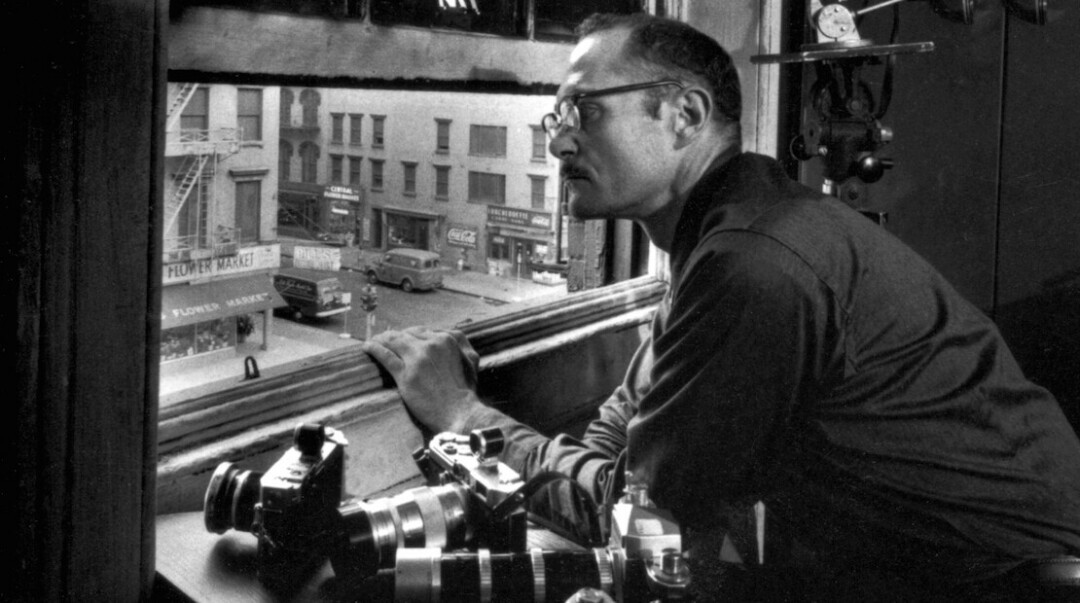

W. Eugene Smith

W. Eugene Smith

I did not know what I was getting into when I queued up The Jazz Loft According to W. Eugene Smith, but when I was done, I was so glad I found it. Not only do you get some great jazz history, but we also learn about photographer W. Eugene Smith leaving behind a family and world-class photography career to live a Bohemian existence in a loft surrounded by jazz musicians.

From 1957 through 1965, Smith, who had been a famous globetrotting photographer for Look magazine, lived in a Manhattan loft and documented the jazz world with photographs and nonstop recordings that he made.

The building where Smith lived was in the Manhattan flower district and it was against the law to live in the building. The loft spaces attracted jazz musicians of all stripes who gathered to jam. We hear from participants such as saxophonist Phil Woods, pianist Carla Bley, composer Steve Reich, bassist Steve Swallow, drummer T.S. Monk (son of Thelonious, who was one of the loft players) and more.

We learn that among the many jazz players Smith photographed and recorded, saxophonist Zoot Sims was one of his favorites, and we hear stories of how Sims could play every other player under the table.

We also learn that the great 1959 Thelonious Monk Orchestra at Town Hall concert was conceived and practiced at the loft, with Smith’s loft neighbor, Hall Overton, who helped Monk orchestrate his music for big band. One of the players from that session said during rehearsal, Monk felt the player was being too academic so he danced the part for him. It’s a truly fascinating insight into the making of the event and the record that followed, but the entire documentary is a really interesting look at the creative spirit.

***

Those three can be seen on Amazon Prime.

Netflix does not have the number of music/jazz documentaries that Amazon has, but there are a couple of great ones. I’m going to mention just one of them – I Called Him Morgan.

The best thing about this sad documentary is that the beautiful, soulful trumpet music of Lee Morgan that saturates the story.

Things start out on a high note, with 18-year-old Philadelphian Morgan being asked to join Dizzy Gillespie’s band, going on the road and challenging the bandleader every night.

“No doubt in anyone’s mind – Lee was going to be a star,” said Charli Persip, drummer from the Gillespie band.

His friends from those days talk about Morgan being a sharp Ivy League dresser who liked fast cars and the company of beautiful women.

One of those friends is the great saxophonist/composer Wayne Shorter, who says it was Morgan who invited Shorter to meet and play with him in Art Blakey’s Jazz Messengers. (I once had the great pleasure of interviewing the famously quirkly saxophonist. I had a million musical questions for him, but he preferred to talk about science fiction rather than music, which was fine with me, too.)

The rest of the Jazz Messenger lineup was Blakey on drums, of course, Bobby Timmons on piano and Jymie Merrit on bass. Shorter talks about how the gravel-voiced Blakey would egg Morgan on during his solos – “Talk to the people,” Blakey would say. “Tell them your story.”

After getting a pretty good idea about the rising jazz superstar that Lee Morgan was, developing the Blue Note sound with the other members of the Jazz Messengers, we then meet Helen, who would come to be considered Morgan’s wife (she is referred to as his wife throughout, but there is never any mention of a real marriage).

Helen was considered a hero of her neighborhood for being her own woman and opening her house to people, feeding and caring for them. That’s how she meets Morgan. By this time, he has been introduced to heroin and has hit the skids. Bandmates tell stories of this time, such as when Morgan showed up at a gig at Birdland in slippers because he had to pawn his expensive shoes for heroin.

Pretty soon, Morgan couldn’t find a job. Saxophonist Bennie Maupin tells a story of being on the subway and seeing a homeless fellow outside his window, and suddenly realizing it was the once sharp Lee Morgan. “He really went down as far as you could go.”

“My heart went out to him, this little boy,” Helen Morgan says in a 1996 interview a month before her death.

Not only did she take him into her life, but she helped him get back on his feet. He went in for methadone treatment, started rehearsing and playing again, but as one club owner from that time noted, Helen “did everything for him.”

“They needed each other,” Helen’s son states. “It seemed to be a good thing.”

And then jealousy reared its head. Morgan met a young woman named Judith Jackson and they started hanging out together. Helen knew something was going on and had made plans to leave to visit friends in Chicago this particular February weekend in 1972. But she didn’t go.

That Saturday night, as an epic blizzard descended on the Northeast, Morgan was playing at a club and Helen decided to stop by. She saw Judith there and got a message to Morgan on stage that Judith had to leave. Morgan physically threw Helen out of the club, and as he did so, she said a gun she carried fell out of her purse. She picked it up, walked back into the club and fatally shot Morgan. He was 33.

It’s a melancholy tale filled with great music.