St. Mark’s still plays significant role in Duluth’s Black community

St. Mark’s African Methodist Episcopal (AME) Church has played a central role in Duluth’s African American community for over 125 years. While other black organizations have dissolv-ed or moved to the Twin Cities, St. Mark’s has been a mainstay.

Rev. Al-phonse Reff, who served St. Mark’s from 1973 to 1984, noted in a 1975 interview that the church’s reach extends beyond its walls. From housing fraternal groups in the 1910s to supporting the fledgling local NAACP to hosting vigils in the 2010s, St. Mark’s has remained a welcoming community space.

Duluth’s African American popu-lation at the turn of the 20th century was small but active. Blacks established fraternal orders, political clubs and newspapers in the port city, mirroring larger establishments in the Twin Cities. Churches were fundamental to the growth and connectivity of the community.

St. Mark’s AME Church was the first and only building in Duluth built by blacks, for blacks. Founded in 1890 by Rev. Richmond Taylor, the congregation first met at Fourth Street and Fourth Avenue West.

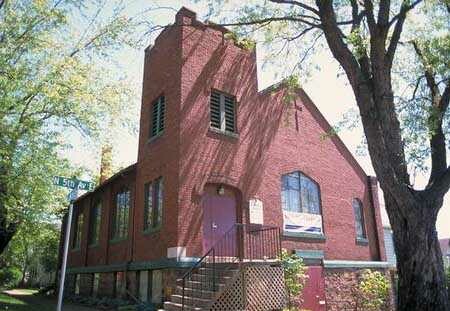

Soon afterward, it moved to a newly constructed building at 530 North Fifth Avenue East. The structure’s basement level accommodated the congregation until 1913, when the main level was completed. The simple brick building sits in a mostly residential area. It features a two-story bell tower, Tudor Revival elements, and locally made stained glass windows.

Like many churches at the time, St. Mark’s in the early 20th century offered the community a central space for religious, social and political conversation and networking. The local Masonic order frequently held meetings at the church, and membership there and in local black organizations overlapped.

At the time of St. Mark’s construc-tion, most African American men in Duluth worked as janitors, waiters, porters or dock or boat workers. A few independent barbershops and restaurants succeeded. Other employment came to Duluth via the U.S. Steel Corporation.

St. Mark’s growth in its early years paralleled the growth of the African American population in Duluth, largely driven by job opportunities at U.S. Steel.

In the early 1920s, the company recruited laborers – many from Southern states – to work at their plant in Morgan Park, a planned community near the edge of Duluth. Recruits found poor wages, unfamiliar weather, and discrimination upon arrival.

Though their jobs were in Morgan Park, the company town, African American employees could not live there. It was a whites-only community. Most blacks settled in Gary, which was also a company town, or the East Hillside neighborhood, near St. Mark’s.

After World War I, Duluth’s blacks faced stricter segregation and harsher discrimination. When the lynching of three traveling black circus workers in Duluth captured national attention in 1920, St. Mark’s was proactive in response. Rev. William M. Majors of St. Mark’s assisted in efforts to indict the lynchers. The National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) provided legal and financial support for the proceedings.

Before the lynching, African Americans in Duluth were not convinced a local NAACP chapter was necessary. After the incident, some outraged and fearful blacks left Duluth altogether. Those who remained formed an NAACP chapter with 69 members, and St. Mark’s provided gathering space for the new organization.

NAACP founder W. E. B. Du Bois was the chapter’s first speaker. In March 1921, he came to St. Mark’s and spoke in favor of Minnesota’s pending anti-lynching law, which the state legislature passed the next month. Ethel Ray Nance, whose father helped establish the Duluth chapter and who became a civil rights leader in her own right, recalled in a 1974 interview that the church far exceeded its 250-person capacity when Du Bois came. She estimated 75 percent of the crowd was white.

Duluth’s black population grew to about 900 by 1970. In 2014, it remained less than 2,000, or 2 percent of the city’s total population. St. Mark’s continues to be central to the community and attuned to racial issues in the 21rst century.

Chronology

1890: St. Mark’s AME Church is es-tablished.

1900: The congregation moves to a building at 530 N. Fifth Ave. E.

1910: Church membership stands at 68.

1913: Main level of building completed.

1920: A white mob lynches Isaac McGhie, Elmer Jackson and Elias Clayton, three traveling African American workers. In response, Duluth forms a chapter of the NAACP that meets at St. Mark’s.

1921: W. E. B. Du Bois speaks at St. Mark’s.

1925: The upper structure is built.

1945: A fire destroys some of the church. With help from the community, the damage is repaired.

1970: The Minnesota Black History Project begins to capture the memories and experiences of Duluth’s African American citizens, many of whom share stories about St. Mark’s.

1991: St. Marks AME Church is added to the National Register of Historic Places.

2012: Pastor Michael Gonzales begins his ministry at St. Mark’s.