More A, B, D.

As a former teacher of English I never expected to find myself in an English speaking society where the (acceptably sexist) Plain Joe Pronoun would earn anywhere near the play received over the past decade. A pronoun is essentially a shorter simpler term that replaces a longer one. After first giving full terms, such as my name, I can then substitute I or me as needed. In English this substitution is essentially automatic and goes mostly unnoticed. Once identified the Declaration of Independence becomes “it”. As language conventions go the pronoun is an easy one.

Or at least it was. You could all but guarantee that when political and sociological started in on grammar there’d be trouble enough to render even Plain Joe Pronoun an identity battlefield. Has to be said that even for grammarian types there can easily be fighting words, but when a political view is attached to grammar we have the situation where the joy of cooking becomes an apology for all the innocent bacterial lives murdered by high heat fry pans. Politics and sociology use grammar, but heaven help us when they set about making new rules. With political views steering them (at times seemingly at the reefs rather than avoiding them) definitions and new rules becomes the individual selecting her, his, their, its, our, or whatever pronoun based on whatever they feel fits their special situation. As rules go that’s not a particularly good one given a lack of anything specific to follow other than what looks like a whim of the moment. This is akin to following directions reading “Go over there somewhere and then try someplace else.”

Now surely, and not to upset them, those who take their pronouns with deadly seriousness along with a cast of dozens of gender term options, there’s a case to be made. But how on earth is dialog or communication furthered by application of unfathomable rules and stipulations that seem to be most handy (and often used) as bludgeons to trash someone for not knowing what was going to offend? Shifting pronoun and gender is like a “Got-Ya” game where the house has all the odds. It’s a poor gamble when one side sets conditions that assure they’ll (or he-she-it-them-our-whom-etc.) always win. If we wouldn’t gamble with those odds neither should we consider them as worthily communicative. Communication is about exchange, a back and forth with a goal of establishing some understanding. It’s not communication when one side insists you follow their loudly insisted on but basically incomprehensible rules. Nor is it communication when we agree to go along. That, when we do it, is what I’d call surrender. I’d also call it an abandonment of reason and order. Abandoning the field of grammar to the harpies of politics does no good for grammar and will never satisfy the not-to-be satisfied harpies.

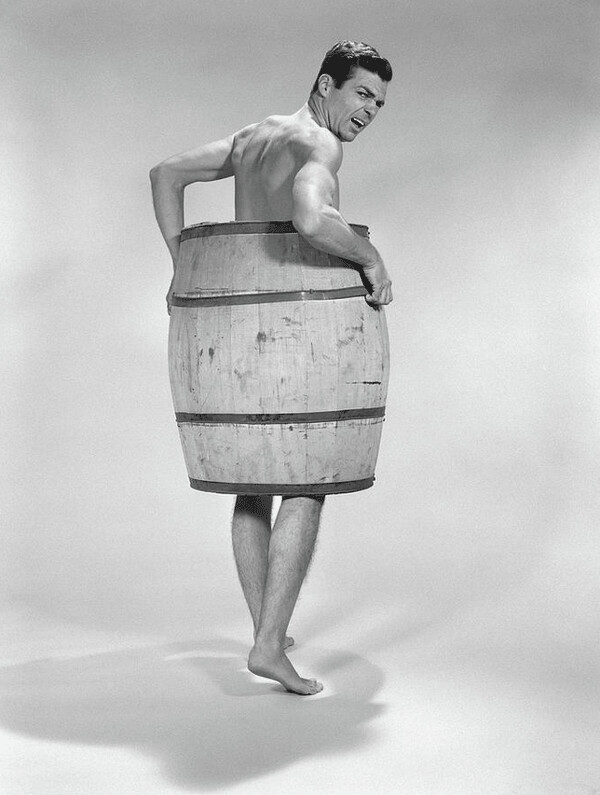

It’s interesting to me how important grammar is and how ungrammatically it so often treated, especially in its political uses. In politic use the term honest may or may not refer to honest as we’d see it put down in a dictionary. Politics makes abundant use of hyperbolic, inventive, and subjective definition where riling up carries more value than does informing. Quite a while ago academics knew The Medium is the Message. Reasonable as that sounds it lacks the snap of functional definition that might put it this was; “In a pissing match the skunks will win” or “A freeway is always louder than a flower garden.” Loud and aggressive force us to pay attention, but not because there’s more there. Loud attracts notice, but it’s also true an empty barrel will make the most noise. A Nun told me about empty barrels. She’s long dead but the truth of her observation carries on.

Surprisingly, one of Tudor England’s more violent and notorious lords wrote poetry about the value of a quiet mind. A functional explanation for that: even harpies need a rest once in a while. The useful fact seems none of us can rely on others to provide a calm mind or give us reflective understanding. Whatever the choice of pronouns and whatnots there’s only one person able to step back and damper the clamor. Only one, and no one can do it for you. It has to be done by yourself for yourself. Now, lots of pronouns there, but I’m confident you’ll figure them out and be just fine, undamaged in ego or persona.

I’ll take a moment here to comment on a truly crucial grammatical element in current politics where the pronouns in “Do us a favor” and “Our country” are contested in meaning. Does “us” imply or is it actually a form of the royal we and our? That is a significant question. In plain speak you get one possibility that’s not very complicated or exciting. In one of the political grammars us and our can only be defined by the user. So if a person says “us” means their split personality that’s what you have to run with, not that you’d have a chance to know beforehand because the “house” has the odds based its rules. But another political grammar says us and our can only mean the royal we and our. I prefer plain grammar as less confusing and more reliable. Can you guess why? Language simply makes better sense if not lumbered with political-sociological rules and limits. Grammar can be difficult. Grammar done politically can be impossible. Does sloppy grammar make good politics?

Dealing with language (which we’re all very good at) is a highly human activity. People can and do define their sense of personal being based on the language they speak. Language is also a form or mental program deeply embedded in us. I don’t happen to believe the world of a native speaker of English is identical to that of someone working to a Mandarin, Hindu, or base in Arabic. Languages may have a word for justice, but that does not guarantee a shared meaning. Don’t be too optimistic. Justice meaning a process of judgment or justice meaning punishment for disobedience are not forms of the same thing.