In Minnesota, when it comes to pro-sulfide-mining rhetoric, look for what is missing

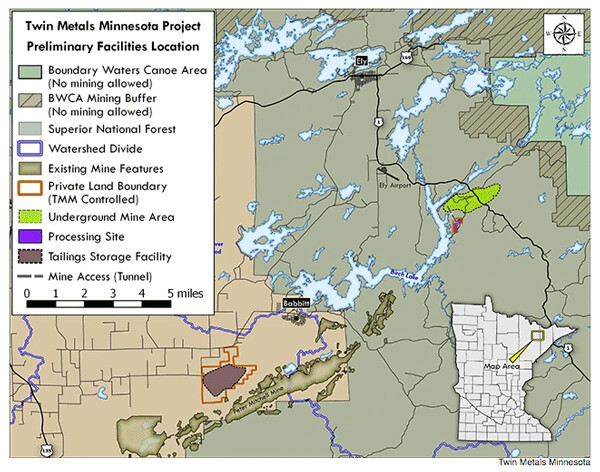

On July 18, 2019, Twin Metals Minnesota suddenly announced it would use dry stacking for tailings waste at its proposed copper-nickel sulfide mine adjacent to Minnesota’s Boundary Waters Canoe Area Wilderness (BWCA).

The press release declared, “It [dry stacking] has been successfully used in four mines in the northern United States and Canada with similar climates to Minnesota and has been permitted at two mines in the western United States.” I’m not sure whether that last phrase is meant to imply that the two permitted mines also have similar climates, but they don’t.

The press release refers to the Pogo mine in Alaska, the Greens Creek mine in Alaska, the Raglan mine in Quebec, and the Éléonore mine in Quebec. Mines permitted to use dry stacking: the Pumpkin Hollow mine in Nevada and the Rosemont mine in Arizona.

The switch to dry stacking was not an altruistic decision, rather industry spin of the probable outcome of the 2014 NI 43-101 Technical Report on Pre-Feasibility Study [PDF]: “Should TMM [Twin Metals Minnesota] not secure the appropriate permits for transfer of water between the basins [Great Lakes and Rainy River], it may be necessary to modify the locations and/or operation of the various Project locations, in order to comply with any inter-basin transfer prohibitions. …

“The TSF [tailings storage facility] is planned to be located within the Great Lakes water basin. Slurries from the concentrator would transfer from the Rainy River water basin to the Great Lakes water basin. Likewise, if the water source is located in the Rainy River basin, but water entrained in the tailings is transferred to the Great Lakes water basin, this too could be construed as an inter-basin transfer. Studies would need to be initiated to confirm permitting and other regulatory requirements in support of such a transfer.”

Apparently regulatory support was not forthcoming. Twin Metals Minnesota now plans to locate its waste in the watershed of the BWCA.

Environmentally unfriendly

Twin Metals Minnesota is a subsidiary of Antofagasta, based in Chile. It claims its potential Minnesota ore contains 4% economically mineable metals, which leaves 96% waste rock and tailings. According to Antofagasta, “These tailings can be safely exposed to air and water because all but trace amounts of sulfides will be removed from them during processing.”

My question: Trace amounts in what concentrations and in what volumes?

Antofagasta’s highly questionable claim ignores the disseminated nature of its resource, the very limited buffering capacity of the host rock, the toxic releases of uneconomical and unrecovered metals and processing chemicals, the massive amounts of unprocessed reactive waste rock, as well as toxic mine drainage and acid (AMD) from overburden, underground workings, and mine dewatering. It can take decades while AMD occurs, often after closure, with perpetual treatment required.

Buffering capacity and permafrost

The term ”dry stack” is not entirely accurate as the tailings have at least 15% moisture content (85% solids versus 50% solids in a tailings basin).

The Pogo gold mine in Alaska uses dry stacking, but unlike the Duluth Complex of Minnesota, the surrounding rock at Pogo has high neutralization potential, hardly an insignificant detail since Antofagasta’s resource does not.

According to the EPA’s 2017 Toxic Release Inventory, the Pogo mine is the fourth largest producer of mining-related toxic waste in Alaska (behind the Red Dog mine, Greens Creek mine, and Fort Knox mine). It is one of the largest mercury polluters in the country. Multiple pollutants measured in excess of limits — even after treatment — including nitrates/nitrites, heavy metals, and chlorides. It has very high cyanide limits. The bond posted is inadequate for long-term water treatment and monitoring. Pogo is located on discontinuous permafrost. There is no under-liner, citing saturation/stability issues.

The Greens Creek silver mine in Alaska uses dry stacking, but the initial Environmental Impact Statement for Greens Creek stated there was little potential for AMD, again because of the buffering capacity of the surrounding rock. Not so in Minnesota’s Duluth Complex. As previously noted, Greens Creek is the second-largest producer of mining-related toxic waste in Alaska. Buffering capacity of host rock could eventually be depleted, resulting in acid generation. In 2003, AMD was documented at Greens Creek. Financial assurance is inadequate for perpetual treatment. Dry stacks have partially re-saturated, increasing leachate, which must be collected and treated in perpetuity.

Significantly, “Between 1978-1980, baseline studies were conducted to understand the pre-mine health of the [Hawk] inlet and to measure future change resulting from [Greens Creek] mine operations. … Since mine operations began in 1987, the State of Alaska has not repeated the baseline study to determine the effect the mine has had on the health of the inlet” (Southeast Alaska Conservation Council). How convenient.

The Raglan (Glencore) nickel-copper mine in Quebec — polluting in excess of toxicity limits for years — is now facing melting dry stack tailings. Raglan dry stack tailings are placed on permafrost, and freeze. Permafrost is melting as a result of climate change. Permafrost. Minnesota may be cold, but the ground is not permanently frozen, nor would Antofagasta’s tailings be.

Dry stacking tailings on permafrost is a spurious comparison to northeastern Minnesota’s water-saturated environment and increasingly extreme rainfall events. What happens when moisture content within dry stacks reaches saturation, highly concentrated leachates release, or inundated stacks trigger liquefaction?

Then there is Éléonore

The tiny Éléonore gold mine in Quebec (3,500 tons per day) “contains iron sulphides such as arsenopyrite. Most of the rock will have a net acid generating potential and will also leach arsenic when in contact with neutral pH water. Under these conditions, the waste rock and the process tailings will have to be managed within an engineered containment system, as required by Directive 019 from the Quebec Environment & Sustainable Development Ministry.” (NI 43-101 Technical Report) [PDF].

Éléonore reminded me that leaching of arsenic is a problem in the Duluth Complex, and with PolyMet (Glencore).

In 2008, scientists within the Minnesota Department of Natural Resources (DNR) expressed serious concerns about PolyMet’s Environmental Impact Statement (EIS), stating, “LTV tailings have been shown by PolyMet testwork to leach arsenic. For the mitigated tailings basin, the use of these tailings for dams and covers (thereby causing disturbance to the existing tailings basin) needs to be discussed in relation to possible exceedance of groundwater standards. Any possible solutions or mitigations to this concern need to be discussed… The EIS should discuss the PolyMet testwork in relation to the “No action alternative.” (Italics added)

As far as I can determine, this discussion never occurred in PolyMet’s EIS, even though the DNR contacted the Minnesota Pollution Control Agency in 2009, stating, “The EIS does not explain the context of arsenic exceedances. PolyMet testwork on LTV tailings resulting in arsenic release should be explained. Possible arsenic exceedances shown in transport modeling for the PolyMet project should be discussed as well as the possibility of any existing concerns with arsenic in the LTV tailings basin related to the no action alternative.”

Minnesotans deserve that discussion now.

Precipitation

Remember the permitted Pumpkin Hollow and Rosemont mines referred to in Twin Metals’ July press release about dry stacking? The closest town to the Pumpkin Hollow mine, Yerington, Nevada, receives 4.83 inches of rainfall per year. Tucson, Arizona, 30 miles from the Rosemont mine site, receives 11.92 inches of rainfall per year. Nevada and Arizona are not comparable to the labyrinth of wetlands, streams, rivers and lakes of Minnesota. It is an illogical, illegitimate, and ludicrous comparison. It proved nothing, except that other states are also struggling to protect their lands and waters.

By the way, on July 31, 2019, a federal judge overturned U.S. Forest Service (USFS) approval of the proposed Rosemont mine, determining that massive waste rock and tailings piles on USFS lands violated federal law.

Climate change

In Alaska and Canada — indeed worldwide — permafrost is rapidly disappearing. “Permafrost degradation is going to affect everything,” says Magdalena Muir, research associate at the University of Calgary’s Arctic Institute of North America. “When you have frozen infrastructure, you don’t have to worry too much about breaches. But as soon as you have soil that behaves just like any other soil, you have all the issues you’d have in southern Canada.” Issues in southern Canada would be much the same as issues in northern Minnesota.

Dry stacking is not a panacea. Pogo, Greens Creek, and Raglan are heavy-duty polluters. Éléonore’s tailings dump would hold 26 million tons of waste compared to Antofagasta’s 2.8 billion tons of filtered tailings. Take a good look at dry stacking at other metal mines, the Minto mine in Canada, for example, unstable and re-saturated.

Tipping point

Hundreds of gigatons of methane and carbon dioxide are trapped beneath permafrost, which is melting faster than predicted.

Waters, wetlands, and forests are Minnesota’s absolutely critical components in the climate change battle facing us. The last thing we need are carbon-spewing foreign corporations extracting and owning Minnesota’s low-grade metals, leaving us with financial liability and environmental decay for perpetuity.

Today, Albert Einstein’s words have never had more resonance, and irony: “Only two things are infinite, the universe and human stupidity, and I’m not sure about the former.”

C.A. Arneson lives on a lake in the Ely area.