Home Runs Are Fun, but Give Me a Triple, Anyway

The All-Star Game is always fun, and usually low-key, and its preliminary home-run contest has become almost as big an attraction. Together, they provide evidence of what a lot of Major League pitchers are grumbling about.

If you watch guys hit home run after home run, do you find the home runs more of an attraction, or less? It seems to me, that when so many are hit, they become so routine as to be less interesting. In this era, we can write off the All-Star Game as being a meaningful and much-appreciated break from the long season.

But it is that long season that is at the forefront, as several teams, including the Twins, and the Milwaukee Brewers, were in need of a respite from recent struggles. The Twins are still in first place, while the Brewers have stayed close and in contention in the National League, but a rejuvenated start to the second half might be pivotal for both teams.

The controversy continues to swirl, and was enhanced, by discussions about the surging increase in home runs in the Majors. And the Twins are the perfect example, because they hit 165 home runs as a team in the first half, and that is one home run short of the total they hit for the entire season last year.

Before the home run derby, ESPN interviewed two players about the numerous home runs — Justin Verlander and Max Scherzer. They are two of the top-tier pitchers in baseball, Verlander for the Houston Astros and Scherzer for the Washington Nationals. An interesting sidelight to the current trend of analytics, and using figure studies to decide trades, Verlander and Scherzer were both stars on the Detroit Tigers pitching staff until both were let go to other teams. The Tigers also had a left-hander named David Price, and a young pitching prospect named Anibal Sanchez. Before letting them all go in deals that were supposedly going to bring in numerous young prospects, the better to rebuild with, imagine what the Tigers would look like right now if Verlander, Scherzer, Price and Sanchez were the four starters in Detroit’s rotation?

Anyhow, Verlander complained that the ball is rewound in a tighter manner and that has led to the increase in home runs. Then they asked Scherzer the same thing, and he said he didn’t notice any difference and didn’t think a livelier ball was an issue.

Having dealt with some issues of balls, bats and other situations with a 35-and-over state amateur league for 20 years, I have several opinions of what has led to the huge increase in home runs. If we give you the livelier ball as one element, here then is a group of six major reasons for all the home runs:

• Livelier ball — See above. Obviously, if the ball pings off the bat with more force, it could lead to more homers.

• The mentality by management that more home runs is a good thing. Looking for players who swing hard, and with an upward trajectory, leads to more home runs, and with that in mind, management doesn’t seem to mind if there are many more strikeouts to go along with the home run increase, prompting management to seek home run or strike out players.

• Harder bats — When our league went away from metal bats to wood, the lighter, cheaper bats were promising, but a new trend was to maple bats, and maple is a stronger, harder wood, which created a lot of harder hit balls that travel a greater distance. Some representatives, who wanted to buy themselves an advantage, wanted composite handle bats, where the unbreakable handle would screw into the wood upper two-thirds for even harder hits. I’ve noticed in the Major Leagues, many hitters use maple bats now. Makes sense, because they’re harder and will hit the ball farther. If the ball is wound tighter, the combination of a harder ball and the long-distance maple bats could be significant.

• The strike zone — I’m amazed to watch games on television and notice that even the guide box that is a television trick to show us where the pitch is now frames an area from the waist to the knees. It used to be that the strike zone was the shoulders to the knees, then the armpits to the knees, then the letters to the knees. The upper edge of the strike zone has continued to be lowered, by umpires’ habits or on purpose. Now it has gotten to the point where a pitch that is waist high is considered marginal, and often called a ball by Major League umpires. Just as often, umpires don’t call knee-high pitches strikes. The much smaller strike zone means the pitcher has to force pitches into a more concentrated area, where the hitters can just tee off. That fact makes me wonder why there are so many strikeouts, when the hitters have such a compressed strike zone to worry about.

• Umpires squeezing the strike zone even more. I am not one of those favoring an electronic-eye strike zone, where any pitch within the strike zone automatically is called a strike. But I would like to see umpires abandon the practice of “squeezing” the strike zone. It is obvious that some umpires will call the corners of the zone tighter in certain situations. Players say that when a pitcher seems to be having trouble throwing strikes, the umpires tend to give them no break, and call fewer strikes on the corners. When I operated in that amateur league, I used to stress recommending to umpires to call a liberal strike zone — letter-high to knees, and definitely calling the corners liberally. The game is more fun when batters swing more, rather than wait for walks. If that questionable pitch on the outside corner is going to be a strike, routinely, then the batter will swing more often at the marginal pitch.

The last one might be the most significant. I watched Max Kepler, a good hitter, go up and take three pitches, all close, and all were called strikes — a three-called-strike strikeout. And he’s a good hitter.

The combination of all those factors has meant that batters go up there looking for a certain pitch in certain situations. That means the hitters might be looking fastball on the first pitch, and maybe on certain other counts, and be vulnerable to taking a strike that is not the pitch they’re anticipating. A hitter like Miguel Sano or Brian Buxton might go up there looking only for fastballs, and be completely suckered by any breaking pitch.

When a Verlander or Scherzer — or a Berrios, Gibson, or Odorizzi — can break a curve ball or slider off that comes in at knee high and then drops like a rock as it arrives, makes them as pitchers so much more dangerous to face. But the last couple of times I watched Berrios, Gibson, and Odorizzi pitch, all three were victims of tightened strike zones.

These guys are artists, and they have a plan for every hitter. Maybe it’s throwing a fastball to a spot to try to get ahead in the count, and then throwing a couple curves or sliders that are just out of the zone, hoping to get the hitter to chase a marginal pitch. If you break off a great slider that ends up nipping the outside corner, but the umpire calls it a ball, then you have to abandon your plan and throw the next pitch a better strike — as in, more in the middle of the plate, which is dangerous to a pitcher’s success. In all three of those cases, the pitchers either walked a batter on a 3-2 pitch (after throwing three strikes, one of which was called a ball), or, worse, had to come in with too good a pitch anticipating the tightened strike zone, and the batter hits it out of the park.

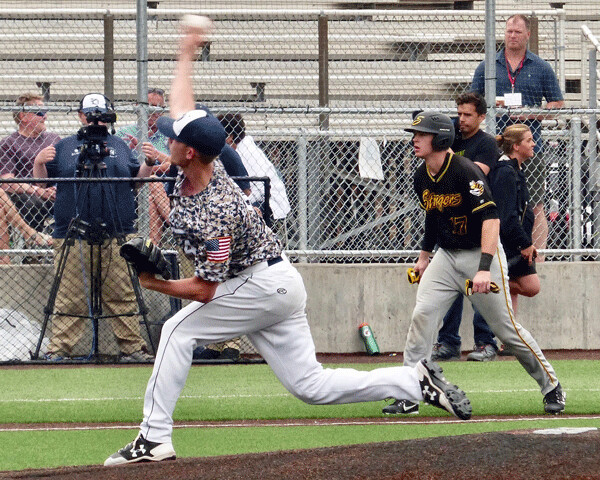

Home runs should be special, not routine. I think it’s exciting that the Twins are hitting so many home runs, but the other night, Miguel Sano hit a single, and then Byron Buxton pulled a line drive down the third base line, into the corner. The Fox television crew followed Sano all the way around from second to third and then home, where he belly-flopped and slid safely across the plate. They showed three replays of that, but they never showed a single replay of the extremely fast Buxton sprinting from home all the way around for a triple.

A triple is the most exciting play in baseball, and Buxton might be the most exciting baserunner in the game. How could the producer not give us at least one replay of Buxton circling the bases? It’s worth talking about, and only part because it prevents us from talking about another (ho-hum) homer!