A Bird in the Hand

The buzz of cicadas gave voice to the heat as we strolled through the shade of giant oak trees. Arkansas in June is a hot soup of humidity. Luckily, it is a short, flat walk from the lodge to the classroom at the Potlatch Conservation Education Center on Cook’s Lake.

This old duck-hunting lodge—once owned by Lion Oil Company—is now operated by the U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service, the Arkansas Game and Fish Foundation, and the Arkansas Game and Fish Commission (AGFC). The educational activities here, which are focused on youth and the mobility impaired, are funded by a statewide 1/8th cent Conservation Sales Tax.

Wearing a uniform shirt with a hummingbird embroidered opposite the AGFC logo, Miss Tana Beasley greeted us warmly as we stepped into the classroom. Long rows of tables and chairs filled the center of the room, while every possible surface along the walls was covered in teaching tools, taxidermy, and snake ID posters. I felt instantly at home, despite the giant alligator and rattlesnake skins spread across a display case.

A retired biology teacher, Miss Tana is the only master hummingbird bander in the state. Such tiny research subjects require a different permit than other birds. Tana has been leading hummingbird banding programs here since 2008. School field trips, civic groups, and now this little group of visitors from the Outdoor Writers Association of America conference in Little Rock, all benefit from her knowledge and skill.

Due to its location along the Mississippi River flyway, Arkansas sees plenty of migratory birds—hence this facility’s start as a duck hunting lodge. Hummingbirds are the smallest avian guests, and some of them stay to breed.

Weighing only 3.5 grams—about as much as a nickel—a ruby-throated hummingbird can fly 18-20 hours straight as it crosses the Gulf of Mexico to or from its wintering grounds on the Yucatan Peninsula. Built to power that flight, the tiny bird’s pectoral muscles make up 25% of their bodyweight (compared to 5% in humans.)

On the mainland, those hummingbirds will fly straight to places where they’ve found food before, and peer indignantly into your window if the feeder isn’t full. They have a remarkable memory, enabled by a relatively large brain for their tiny size. Before banding studies were done, scientists guessed that they could only live 3-5 years. Now we know that they can live up to 12 years and return annually to the same feeders.

After the background lecture, Tana situated herself at the banding table, with all of her tools laid out neatly. I saw many similarities between her and Jim Bryce, who bands songbirds with our Master Naturalist course on the Moquah Barrens each spring. Soft-spoken, methodical, gentle, and precise, these two show a special reverence for their subjects and excitement for what birds can teach us.

With Tana at the ready, Wil Hafner, an AGFC educator, headed out the back door to show us the specially made trap. With trap’s doors open, a swarm of hummers buzzed around three feeders hung inside. When Wil closed the top doors, the hummers flew up to try and escape, and he put his hand in through a lower door to carefully scoop a single bird into a small mesh bag.

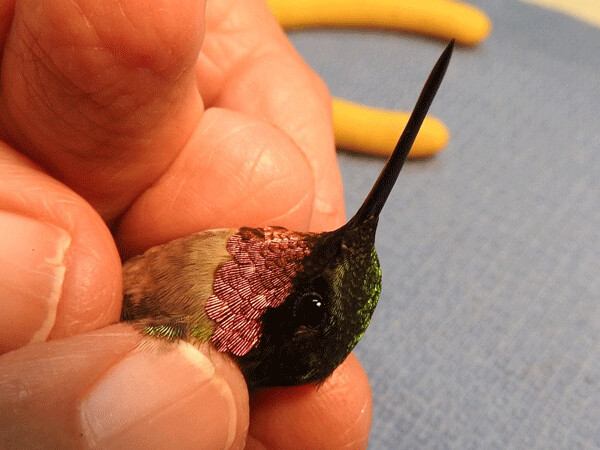

We enjoyed our close-up view of the others as they stuck their heads through the wire mesh that was precisely sized to avoid injury. Going eye-to-eye with a young male, I was thrilled to examine his striated throat up close. Tana had explained that these dark stripes on his white chin are sheaths surrounding what will become iridescent red feathers once he matures. After this brief encounter, Wil opened the top of the cage so the parade of hummers could zoom away.

Inside, Tana used a little piece of nylon stocking to swaddle the hummer while she clasped a tiny band on its leg; measured wings, tail, and beak; weighed it; and then checked for fat by blowing on its belly through a drinking straw. As she manipulated the little guy, we gasped in awe as his throat feathers caught the light and turned from black, to purple, to ruby. This was definitely a mature male. So I was confused to see a featherless patch of skin on his belly revealed from Tana’s puffs of air.

In most birds—like the ones Jim Bryce catches—the females will pull out feathers on their brood patch to allow for the efficient transfer of body heat to their eggs. With their long beaks, though, hummingbirds can’t reach their own bellies. Their brood patch is automatic, and it occurs on both males and females, even though the guys never sit on the nest.

When we recaptured a female who had been banded just 10 days prior, the puff of air revealed the pale lump of an egg developing under her skin. Tana worked more quickly then, not wanting to interrupt this mama’s important business.

Each of us students released a banded hummingbird during the program. My mom was tasked with releasing this mom. Outside the classroom, Tana arranged my mom’s hand out flat and then carefully pressed the tiny bird’s warm belly against her skin. Mom’s smile grew as she felt the heat and racing heartbeat. We readied our cameras. Tana let go. Immediately, the tiny jewel zoomed off in a shimmer of green, leaving my mom grinning with delight.

For as long as I can remember, we’ve had a hummingbird feeder near the kitchen window so that Mom (and all of us) could enjoy the antics of her favorite birds. They are fun to watch, of course, but there is nothing quite like actually having a bird in your hand.

(View more photos and videos of the banding process at http://cablemuseumnaturalconnections.blogspot.com/)

Emily’s second book, Natural Connections: Dreaming of an Elfin Skimmer, is now available to purchase at www.cablemuseum.org/books and will soon be available at your local independent bookstore, too.

For more than 50 years, the Cable Natural History Museum has served to connect you to the Northwoods. Come visit us in Cable, WI! Our new Curiosity Center kids’ exhibit and Pollinator Power annual exhibit are now open!