Uber and Lyft, driving drivers into poverty and despair

Early on Monday morning, Douglas Schifter, a career professional taxi and limo driver in New York City, made one final trip, to lower Manhattan. Several hours earlier, he posted on Facebook a condemnation of leading politicians for allowing ride-hailing companies like Uber and Lyft to gut the taxi industry in the city, forcing him and thousands of drivers into poverty. Parked in a rented black sedan at the gates of City Hall, he killed himself with a gunshot to the head.

“Due to the huge numbers of cars available with desperate drivers trying to feed their families,” Schifter wrote, “they squeeze rates to below operating costs and force professionals like me out of business. They count their money and we are driven down into the streets we drive becoming homeless and hungry. I will not be a slave working for chump change. I would rather be dead.”

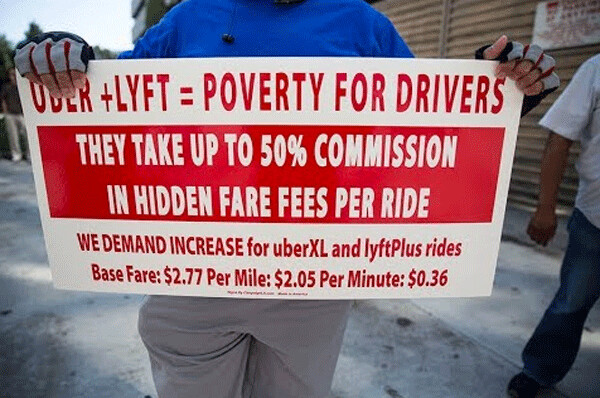

Most major cities have long regulated taxis, limiting the number of licensed cabs and requiring strict adherence to insurance and safety standards. Uber and Lyft, the principal ride-hailing or “transportation network companies” (TNCs), have managed to skirt those laws, flooding the streets with cars. “There used to be only about 13,000 yellow cabs and another 40,000 liveries and black cars combined,” Bhairavi Desai, executive director of the New York Taxi Workers Alliance, a nonprofit union with over 19,000 members, said on the “Democracy Now!” news hour. “Now you have over 130,000. Nobody can earn a living.”

A new report by the National Employment Law Project and the Partnership for Working Families, titled “Uber State Interference: How Transportation Network Companies Buy, Bully, and Bamboozle Their Way To Deregulation,” states: “TNCs, primarily Uber and Lyft, have convinced legislators in the vast majority of states to overrule and preempt local regulations and strip drivers of rights. The speed and sweeping effectiveness of the industry’s use of this strategy, known as state interference (or preemption), is unprecedented.” They liken the lobbying tactics used by Uber and Lyft to those of the tobacco and gun lobbies, and identified 41 states where this aggressive lobbying has loosened or eliminated the rights of cities to regulate ride-hailing companies.

“It’s a race to the bottom,” Desai told us. “In 2016, Uber and Lyft combined spent more on lobbying than Amazon, Walmart and Microsoft combined. They use their political might to win deregulation bills. Most of their lobbyists, by the way, come out of the Democratic Party. Many of them went straight from the Obama White House to work for Uber.”

Douglas Schifter’s death was preceded by another suicide, weeks earlier. Danilo Corporan Castillo jumped to his death on Dec. 20, following a hearing before New York City’s Taxi & Limousine Commission, or TLC, where they threatened to revoke his license. He wrote a suicide note on the back of his TLC summons.

Last April, Bhairavi Desai testified before the TLC, an odd acronym for a commission known not for showing the city’s cabdrivers much “tender, loving care,” but, rather, for imposing draconian fines for innumerable minor violations. Desai said: “Half my heart is crushed, the other half is on fire. In my 21 years of organizing in this industry I have never seen people in such crisis: the bankruptcies, the foreclosures, the eviction notices. I now take phone calls about homeless services, people wanting to know about suicide-prevention hotlines ... this is a serious human crisis because of the financial plague that has happened in this industry.”

Desai advocates for a cap on the number of licensed cabs and other car services, use of taxi meters across the various car services to ensure a livable wage for drivers, and access to benefits, primarily health care, for drivers. In addition, the National Employment Law Project and the Partnership for Working Families say state legislatures need to stop doing the bidding of Uber and Lyft.

“The whole purpose of life is to learn, teach and love,” Douglas Schifter wrote in his final Facebook post. In addition to driving for four decades, he was a prolific columnist for the limo driver magazine Black Car News. “I don’t know how else to try to make a difference other than a public display of a most private affair,” he continued. “I hope with the public sacrifice I make now that some attention to the plight of the drivers and the people will be done to save them and it will have not have been in vain.”