Hillside hoarding case concludes for now

In the Nov. 9 issue I wrote about Shelly Louks, an elderly, disabled Central Hillside tenant who was due to be thrown out of her home over circumstances not of her making. A city fire department inspector had condemned the other apartment in the duplex because the tenant (who requested her name be withheld from print) was hoarding an excessive amount of books, papers, furniture and other belongings, creating a fire hazard. That tenant lives in the upstairs unit while Louks lives downstairs.

This case had been dragging for a year, as the upstairs tenant slowly worked on reducing the amount of stuff. She kept appealing the condemnation order through her lawyer. In July the appeal went to all the way to City Council, which affirmed the condemnation but gave the tenant until mid-October to clean up.

October arrived and the tenant failed to make satisfactory progress. On Nov. 7 the inspector pasted an “unlawful human occupancy” notice on Louks’ door, stating she would have to vacate by Dec. 18, even though her apartment wasn’t the problem.

The next day, Nov. 8, the inspector sent Louks a letter that “the right to appeal was accidentally left off the form,” not exactly inspiring confidence in the process. The letter said Louks could file an appeal for $120, not easy money for a low-income resident.

The inspector, Greg Smith, did not return my phone calls that week, but as it happened, I ran into him Nov. 15 when he got in line behind me at a grocery store. (He was hard to miss since he was dressed in a blue uniform with his name on the label.) I introduced myself and said I was still waiting to hear from him. He said he’d been busy (though he had time to speak to the Duluth News Tribune for their Nov. 10 article on the matter) and said he would call the next day.

He did call as promised and I asked how he could affect the downstairs apartment when the condemnation was for the upstairs unit only, a point specifically mentioned in the City Council resolution. He replied that the downstairs unit wasn’t condemned; it was under order to vacate because the rental license for the entire duplex had been revoked. If that’s not in keeping with City Council’s intent, it seems a legalistic way around it.

Meanwhile on the evening of Nov. 15, Mayor Emily Larson was holding one of her “City Hall in the City” sessions in which she invites citizens to meet with her and other officials to address their concerns. Louks wanted to attend the session at Glen Avon Presbyterian Church, but she was afraid her night vision was too bad for her to drive. So I offered to give her a ride and she accepted.

As it turned out, Larson and Louks knew each other from the early 2000s when Louks was on the board of the Gabriel Project, a now-defunct social action organization sponsored by local churches, and Larson was the director. After hugs and pleasantries, Louks told of her dilemma. Larson suggested Louks get support and legal advice, suggesting One Roof Housing and city councilor Barb Russ, who is an attorney.

Now I understand the mayor can’t pull strings for old friends, but here she’s telling someone how to independently seek protection from the city’s actions. Isn’t the point of these mayor’s sessions to make it so people don’t have to do that? (Russ turned out to be of no help, declining to return phone calls from myself and Louks’ landlord, Karl Wyant.)

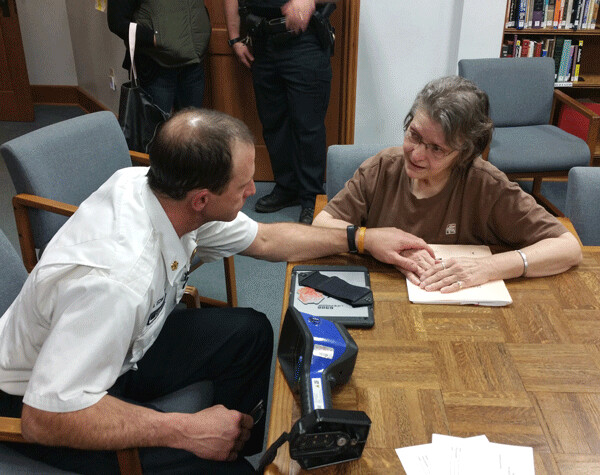

Duluth fire chief Dennis Edwards was also at the meeting and the mayor deferred to him. But he could do little more than hold Louks’ hand and sympathize about her being caught in the crossfire as she sobbed about how she was going to be homeless.

Finally, Edwards offered to talk about it at her home, and bring Smith along, on Nov. 21. Louks asked if I could be there as a witness. Edwards firmly said, “No. No reporters.” Now here’s an odd proposal to make at a “meet your public officials” event. What did he plan to tell her that he didn’t want anyone else to hear?

I wondered if Edwards had the right to keep me out and later spoke to Mark Anfinson, a Twin Cities attorney who specializes in First Amendment law. Anfinson said they weren’t required to hold the meeting and therefore could determine who would be there, but a citizen also has the right to tape-record the conversation without the city officials’ awareness.

Louks was open to the idea and Wyant offered to provide the recorder. Ultimately, though, she decided she didn’t want any more city officials around her place, considering her interactions with them so far. Instead she had a phone conversation with Edwards, who told her another inspection of the upstairs apartment would take place Dec. 1. If it didn’t pass, the landlord could evict the tenant and get his license back, in which case Louks wouldn’t have to move.

OK, couldn’t this arrangement have been worked out before Louks got a red sign glued to her door? Here the inspector and the landlord blame each other: Smith said it’s Wyant’s responsibility to keep the property safe and eviction is a tool he could have used long ago. Wyant said he was reluctant to evict someone with a mental illness and he accuses the inspector of “overreach of government.”

Smith inspected the upstairs apartment again on Dec. 1 and, at last, deemed it sufficiently cleaned up. Wyant paid $525 to get the rental license reinstated and Louks can stay. So the situation is resolved at least for a year, when the inspector revisits upstairs to see if it’s filled to the scuppers again.