Taxes, fees and swearing

On September 8, 2016, Mayor Emily Larson presented her 2017 budget to the city council. One big change involved converting the city’s fee-based street utility into a levy-supported operation. The monthly fee, which is currently added to every customer’s utility bill, would be eliminated, and property taxes would be raised enough to generate the same amount of money. Mayor Larson called this a “revenue-neutral” switch, saying also that she believed a levy was fairer than a fee, because everyone had to pay the same fee regardless of income, whereas with a levy people paid an amount based on the value of their property.

Currently, the street fee is $5 a month for most homeowners, and raises a total of about $2.8 million annually. The new levy will raise the same amount. Although the switch is revenue-neutral in terms of the overall budget, individual people will see modest changes. The mayor said that an average $160,000 home would pay approximately $18 less per year under the new system, while the owner of a $225,000 home would pay about $3 more. She described the budget as “Minnesota plaid and practical.”

Another, similar element of the mayor’s budget involved replacing part of the city’s street-lighting fee with a levy as well.

To replace the street fee with property tax, the levy must be raised by about 13 percent. To reduce the streetlight fee, the levy must be raised by another 2 percent. The mayor also added slightly less than 2 percent to the levy for general operations, which is not unusual (the county is raising its levy 8.5 percent). In total, the city’s levy could rise by as much as 17.65 percent, for a total revenue capture of more than $25 million—a massive increase, but one mostly offset by the disappearance of fees. Chief administrative officer Dave Montgomery told councilors that “most homeowners in the city…will come out ahead,” paying somewhat less with the levy than with the fees. Of course, some homeowners—the wealthiest ones—will pay somewhat more.

The second big change in the 2017 budget is Minnesota Power’s franchise fee. As a public electric company, Minnesota Power pays the city of Duluth a fee for the right to run power lines on city streets. This fee has been $1.1 million for many years. Mayor Larson proposed tripling it, to $3.3 million.

Such a change would have an immediate impact on Duluthians, because Minnesota Power passes its franchise fee on to consumers. It appears as a line item on your electric bill—last month I paid 49 cents for the “Duluth Franchise Fee.” If the fee triples under the mayor’s proposal, I will be paying about $1.50 per month, or $18 per year. Heavy users of electricity will pay much more. Representatives of the Verso paper mill in West Duluth, who lobbied the city council in opposition to the new fee, estimated that it would cost them more than $500,000 more per year to operate. The city administration contends that the fee is currently very low compared to what other communities charge, saying that the new fee would bring Duluth in line with the rest of the state.

Revenue-neutral or not, fees and taxes are never popular. At the September 26 city council meeting, councilor Howie Hanson was particularly vocal in his criticism of the budget.

“This clearly is a shell game,” he said. “It would be great if this city would finally get its financial house in order and take this new business growth [that the city has experienced] and re-invest it back into REAL issues and real needs that we have in this city, such as the aged infrastructure, which is rotting to hell, frankly…. You know, I had hoped that transparency would be one of the hallmarks of this current administration, but in fact we’re continually playing wordsmith games, and I’m really frustrated about that. I’ve been frustrated in the first three years on this council, and will continue to be frustrated, I think, unless changes are made about being truthful about what we’re doing here….This city is in financial ruin. Mr. Montgomery understands this very well, and we’re looking under every rock for every dollar to help support a rising general fund budget….Let’s get truthful, let’s not talk down to the common Duluthian who is trying to survive from day to day, and certainly month to month, let’s have a good, honest, truthful conversation about the needs that we have in this community. To say that people are better off [paying a levy rather than a fee], that’s a bunch of bullshit.”

Well, that was nice of him—accusing the administration of being dishonest, untruthful, and non-transparent, especially with profanity, is always a good way to make your point. Hanson’s anger undoubtedly reflects that of some of his constituents’, but accusing the administration of playing shell games and not being transparent implies that the administration is being devious, which is unfair. Though one may disagree with the budget, it is a very clear budget. Mayor Larson and city staff have explained it repeatedly—at news conferences, at council meetings, via email and in the newspapers. I don’t know how much more transparent they could be.

Hanson’s concerns notwithstanding, the council approved the mayor’s budget by a vote of 5-2. Hanson returned to his bellyaching at the end of the meeting, during the time reserved for councilor questions and comments. He veered all over the map, first complaining about fees, then about the levy, then about the previous administration, then about the current administration, then about how nobody on the council respected his dissenting view. Finally, he got back around to profanity.

Councilor Hanson: What the people of Duluth really want to hear is what the heck is going on here? Why are we being fee’d? Why are our taxes going up? Why are we putting places like the paper mill at risk? You know, what is going on here? Let’s just have a healthy conversation....What’s happening here is we’re playing this little shell game that, frankly, I don’t want to play anymore. And for as long as I’m gonna be on this council, I’m gonna keep talking the truth, because the truth is what people are asking for, and they really want to hear. And our reputations as councilors are on the line here. So let’s cut the bullshit. Let’s begin to have an honest discussion and be leaders and have the courage to tell people the truth, to give them the answers to what they deserve. They are our stakeholders. People in this town are literally making choices between food, heat, health care, being able to stay in their houses….We should fight as hard as we can to be honest and truthful with people, and to begin to care and do what we can to help them. And the best place to start is right here in these chambers, is to be honest and to work our balls off, if you will, to put together a budget that is real and honest and not gonna drive people out of their houses.

In a way, councilor Hanson’s grandstanding did bring people together: When he mentioned balls, everybody cringed.

The truth

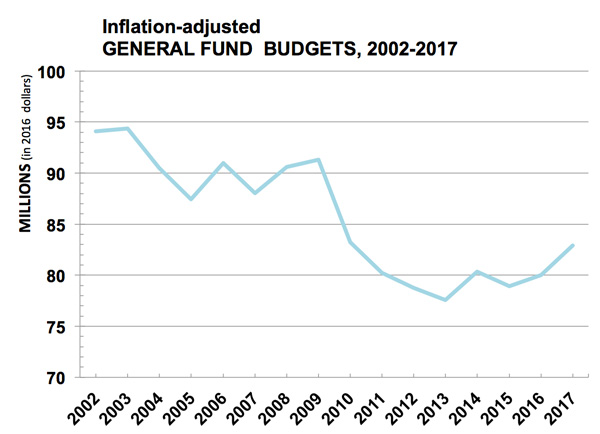

truth is that the city needs money. The city’s general fund budget has been shrinking for many years. Much of the blame dates back to 2008, a year when Duluth experienced the housing bubble crash, a loss of investments, a reduction in local government aid from the state, and high gas prices, among other problems. Between 2009 and 2010, the city’s general fund dropped from $81 million to $75 million as the city struggled to cope with its problems. Since then, the general fund has slowly inched back up. In 2016, for the first time in eight years, the budget climbed back above $80 million. When one adjusts for inflation, however, the city still has not returned to its pre-recession levels. Indeed, if one adjusts for inflation, the general fund today is considerably smaller than it was in 2002 (see graph).

Along with the smaller budgets, the city’s obligations have increased; today, the city pays out $9 million per year for retiree healthcare that it didn’t pay in 2008. The costs of materials and wages have also gone up.

On the bright side, the city’s long-term street debt is declining. One way that Mayor Don Ness responded to the 2008 crash was to not borrow any more money for street repair, but to adopt a pay-as-you-go approach. This started the city’s street debt down a different road—instead of constantly growing, it began a steady decline. Between 2009 and 2014, the city took nearly $40 million from the Community Investment Trust (CIT) fund to pay for streets and street debt. Today, the remaining street debt is $8.5 million; if the city continues on its current path, it will be paid off by 2024.

(The city is no longer taking money from the CIT fund for anything, choosing instead to leave it alone as a hedge against hard times. The CIT’s balance is currently about $20 million—it is the last substantial, undesignated pot of money in the city.)

The downside to paying as you go is that streets are expensive. Whether the city raises $2.8 million a year for streets via fee or property tax, more than half of that immediately goes to pay off the debt. In essence, the city’s limited street budget is an unavoidable consequence of trying to put the city on a sustainable footing. In 2014, we only reconstructed about six blocks of city streets. In 2015, it was a little more. If not for the county, state and federal funds that help us with many of our streets, there would be hardly any street repair taking place in the city at all.

This may not change any time soon. Without steep levy increases, it will be tough for the city to get substantially more money for streets. Although Duluth is showing signs of economic vigor—new construction, an expanding tax base, the public perception of a cultural “renaissance”—we cannot shake off the effects of the past overnight. Because things are looking up economically, this is exactly the time to continue behaving frugally and cautiously—to bake the gains in, if you will. When we’re done paying off the debt, ALL the money can go to streets—and we will have had so many years of living within our means that it will seem like a veritable windfall.

Though we can, and should, argue over details—like, couldn’t we phase in that Minnesota Power franchise fee over a few years instead of dumping it on the city all at once?—overall the Larson Administration’s first budget demonstrates clarity and leadership.