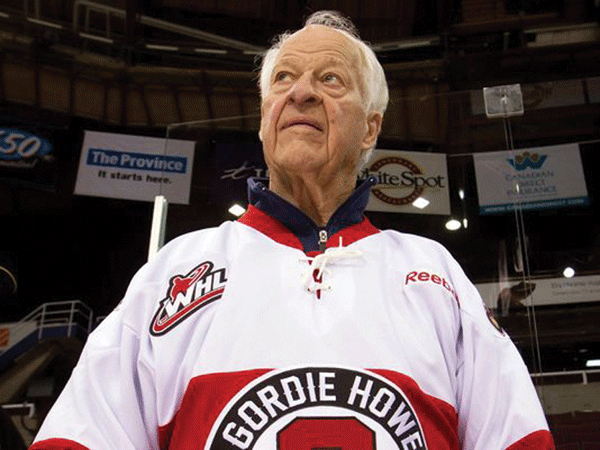

Gordie Howe Stories Best in First Person

It was fully appropriate that the whole thing felt surreal. Other-worldly, as they say. I was off on a fabulous trip to Spain, where Volvo was introducing its new S90 sedan, and because it is world-class, Volvo made it worldwide by inviting motoring press folks to Malaga to experience driving the vehicle.

We had been bused to the Kempinski Hotel and Spa in nearby Estepona, Spain, where you could walk down a level to a series of swimming pools, and you could walk down another level and stick your toes in the Mediterranean. In my room, fighting jet-lag, I found a European version of CNN with English-speaking reporters. I was watching the lengthy funeral procession for Muhammad Ali, who had died earlier last week.

Right then, my iPhone chirped, and I received a text message from my younger son, Jeff. He said that Mr. Hockey had died, and asked me to relay my favorite story of interviewing Gordie Howe.

One of the benefits of aging in the media business is that you can be humored by younger writers scurrying around to try to locate former teammates and foes of Gordie Howe to extract stories about him after he died at age 88. It’s so much better to have watched him play, covered games in which he played, and marveled at both his hard-nosed and uncompromising play on the ice, yet still converse with him in his soft-spoken and mellow demeanor. It could be in the dressing room after a game, or someplace like the Warroad Celebrity Golf fund-raising tournament, where Gordie was the featured attraction one year, and enjoyed the down-home treatment he received so much he came back on his own the next year.

Gordie made up his own rules, and played the game his own way. He never complained, never barked at a ref that I know of. If somebody did him wrong, he would take care of it himself. He didn’t need referees to officiate his games, because he officiated them in his own fashion.

One of my favorite Howe stories came after he had retired from the Detroit Red Wings but then unretired to join two of his sons, Mark and Marty, and play for the Houston Aeros of the upstart World Hockey Association. He brought with him the reputation for making his own rules as he played, and the Gordie Howe Hat Trick already was declared as scoring a goal, getting an assist, and getting into a fight in the same game.

Writing for the Minneapolis Tribune in those days, I got to cover high school hockey, college hockey, and the Minnesota North Stars of the NHL. So when the WHA started and the Minnesota Fighting Saints were a charter member, I added them to my list of responsibilities. The Saints were a raucous, fun-loving, hard-living gang that had talent, toughness, and the amazing humor and spirit of the late Glen Sonmor as general manager and Harry Neale as coach.

After the NHL all-stars played the 1972 international series against the Soviet Union’s fantastic team of non-pro superstars, the WHA decided to do the same thing in 1974, with the first four games in Canada and the other four in the Soviet Union. I got the chance to cover the first four games, in Quebec City, Toronto, Winnipeg, and Vancouver.

The USSR had the incredible forward line of Vladimir Petrov centering Boris Mikhailov and Valeri Kharlamov – an amazing talent who was Wayne Gretzky before Gretzky. This was, in my estimation, the greatest line in hockey history. Always skilled enough to tantalize North American foes with their great puck-control and unexcelled discipline and passing wizardry, it had become a certainty that Canadian players would commit various atrocities against Soviet players, and claim they had done some dirty work with their sticks to provoke it. North American officials went along with it as if they were part of that charade.

From the press box in one of the games, I observed Gordie Howe take a quick, nasty two-hander that felled Kharlamov. After the game, the media seemed more intimidated by Howe than any opponent. I had interviewed him various times, and had no such reluctance to approach him. I walked up, without the usual crowd of other reporters listening in.

“Gordie, Kharlamov must have done something to you,” I began.

“Who?” Howe replied.

“Kharlamov. Valeri Kharlamov, No. 17,” I explained. “I figured he must have done something to you, because I saw you drop him with that two-hander.”

“Oh yeah,” Howe explained, calmly. “He committed a no-no. He tried to skate between me and the net.”

Wow. There was vintage Gordie Howe, casually explaining one of his unwritten rules. You skate between me and the net, and I’ll chop you down.

He played without compromise, and he never whined. If an opponent gave him a two-hander, or hit him with a stick on top of the head, he wouldn’t say a word, to the ref or his adversary. He would, however, savor the opportunity to get out on the ice against such a perpetrator, and soon.

Howe was remarkably skilled as a player. I have an old saved notebook from 1976, when Howe scored his seventh game of the season in a game against the Fighting Saints. Seven goals wasn’t much for a midseason game, but Howe was 50 years old at the time.

Powerfully built, Howe didn’t have big, square shoulders; instead, his muscular shoulders drooped down at a steep angle on both sides, but they had such power he could fire a puck with the best of them. He scored 802 goals, and 1,850 points in 1,767 NHL games. He added more in the playoffs, especially while winning four Stanley Cups, and many more still during six years in the WHA with Houston, and a couple more with New England. He had three 100-point seasons – all after he was 40 years old. He won six scoring titles in the NHL and six most valuable player awards as well.

He was as feared for his determination to go through you to get to the puck, and to sometimes use his stick to clear a path. You could use yours on him, but be prepared for a vicious payback. One of his most amazing skills was that he could change hands on his stick and, a natural right-handed shooter, shoot nearly as well left-handed. I saw him in a skirmish in front of the net one time when a rebound popped out to the side, and he changed hands and scored left-handed before anyone knew what happened. I also saw him skate in on a breakaway, deke, then switch hands to score.

How was inducted into the Hockey Hall of Fame in Toronto in 1972, before he came back in the WHA, and long before dementia started stalking him. He suffered a stroke in 2014 that even his family was pretty sure would end his life. But he battled back, and even ventured to Mexico for some stem-cell work that was not yet approved in the U.S. He came back from that, and still made public appearances. He was visiting his third son, Murray, when a final stroke ended his life.

The game has changed from when there were only six teams, and Gordie Howe faced Bobby Hull from Chicago, Bobby Orr from Boston, and Guy Lafleur, Jean Beliveau and the army of great players from Montreal. One of my biggest thrills as a sportswriter was when expansion brought the North Stars, and I was able to see those legends in person after only seeing them on television.

More star players followed, like Wayne Gretzky, Mario Lemieux, and now guys like Sidney Crosby, among others. When Pittsburgh prevailed to beat San Jose in six in the Stanley Cup finals that ended Sunday night, I was prepared for a classic game. The San Jose crowd was primed, and big Joe Thornton prepared for the opening faceoff against Crosby. The puck was dropped, Thornton won the faceoff by pulling the puck back to a defenseman, then curled and skated after it. He had taken about two strides when Crosby, inexplicably, shortened up on his stick like it was an ax, and chopped Joe Thornton across the back of his left knee, where there is no protection.

Thornton turned and the two jousted briefly with high sticks, then were separated. Incredibly, no penalty was called on Crosby. If that had happened in reverse, and Thornton slashed Crosby on the back of the leg after the opening faceoff in Pittsburgh, you can be guaranteed that Thornton would have gotten a penalty, and maybe a major.

The problem I have with Crosby is that when anyone gets near him, he whines to the officials. I thought he had improved in this final series, although when a whiner pulls off a cheap slash from behind, it seems just that much more cowardly. Amazingly, Crosby was given the most valuable player in the playoff award, although he failed to score a goal in the finals.

His flagrant cheapshot made me realize that, in retrospect, Thornton should have dropped his gloves and pummeled Crosby on the spot. They probably both would have gotten five for fighting, and if the officials reviewed it, they would have seen the instigating cheapshot that they incomprehensibly missed.

Think about the game’s recent superstars. You never saw Wayne Gretzky chop someone with a two-hander from behind. Or Neal Broten. Or Pavel Datsyuk. In fact, there was only one true superstar who could score and pull off the occasional cheapshot, and still be thoroughly admired. And he just died.

Rest in peace, Gordie Howe.