Euthanasia and Will Shakespeare

A Tough Question For Any Day: “To Be, Or Not To Be”

A Tough Question For Any Day: “To Be, Or Not To Be”

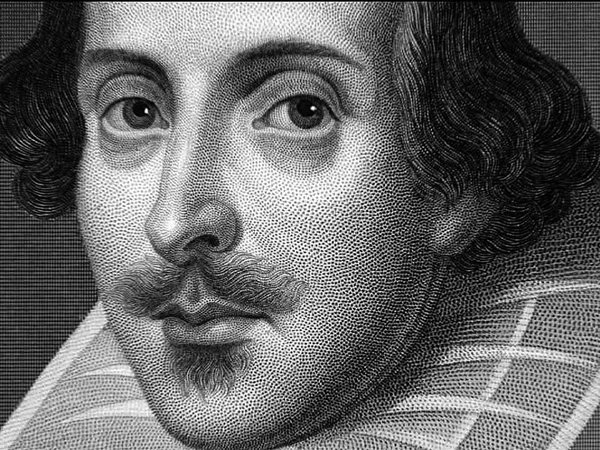

Two very important issues were presented to the world on the 400th anniversary of the death of the world’s greatest playwright and poet, William Shakespeare. Pope Francis, in his “Amoris Laetitia” (The Joy of Love), struggled to answer some of the questions about sex and all that that the Roman Catholic Church has been struggling to answer for many centuries. Justin Trudeau, the newly elected prime minister of Canada, promised the Canadian people he will legalize aid in dying for terminal patients. A majority of Canadians approve assisting people under certain conditions if they are terminally ill. Trudeau had watched his father Pierre, a former prime minister of Canada, die a “long, agonizing” death from prostate cancer and Parkinson’s Disease. Shakespeare, in his poems, sonnets, and 37 plays, often examined both sex and dying with intelligence, grace, and humor. Hamlet is my favorite Shakespeare play, maybe because I taught it to high school seniors at least 50 times, maybe because it concentrates on life and death and the possibilities of afterlife. It has the love and sex of the pope’s The Joy of Love, and the homicide and suicide of aids in dying proposals discussed in Canada’s Parliament and recently in a bill brought to the Minnesota Legislature. In the most famous soliloquy in English literature, Prince Hamlet agonizes over what action, if any, he should take against his uncle who has murdered his father the king and then married his mother the queen (there are many exciting scenes!):

“To be, or not to be—that is the question: whether ‘tis nobler in the mind to suffer

The slings and arrows of outrageous fortune or to take arms against a sea of troubles

And by opposing end them. To die, to sleep—no more—and by a sleep to say we end

The heartache, and the thousand natural shocks that flesh is heir to. ‘Tis a consummation

Devoutly to be wished. To die, to sleep—to sleep—perchance to dream: ay, there’s the rub, For in that sleep of death what dreams may come when we have shuffled off this mortal coil,

Must give us pause.”

Shakespeare, with his vocabulary of 30,000 words as compared to the 2,000 words most modern persons use in communicating with their publics, developed plots from history such as Richard III and Henry IV, and ordinary scenes from life such as All’s Well That Ends Well and Much Ado About Nothing. And then we have the great story about love and sex in his Romeo and Juliet. The British National Library has on display a battered copy of The Collected Works of William Shakespeare once owned by Nelson Mandela, the eventual president of South Africa. It probably had maintained his sanity during his 27 years of imprisonment on Robben Island. He often read it to his fellow inmates although English was not his mother tongue. Mandela said he gained inspiration, solace, and wisdom from the great characters in the plays, and has said: “Shakespeare always seems to have something to say to us.” There are hundreds of great characters in his plays—but think Romeo, Macbeth, Lady Macbeth, Prospero, Caliban, Shylock, Othello, Falstaff. The list is endless.

The Battle Over Euthanasia

I would like to clear up one misunderstanding about Shakespeare and his relationship with his wife Anne Hathaway. Some critics have suggested that Will did not think much of Anne’s abilities in bed, so in his will he bequeathed her his “second–best bed” in their Stratford house. Actually, in 16th Century construction the first bed, a canopied rather huge edifice, was part of the framework of the house, so it was difficult to remove without demolishing the house. Now, back to the real stuff….

In his monologue, Hamlet is posing the question whether he should live or die, whether he should attempt to solve his problems “by taking up arms against them,” or commit suicide “to end the heartache” of the awful pain. Those are the same questions liberals and conservatives face today in the discussions over euthanasia. Prime Minister Trudeau said, “It’s a deeply personal question.” The central question about legalizing aid in dying seems to be: Is pain and suffering an unfortunate, unlucky, but humanizing experience, or are we involved in a personal tragedy we can try to prevent? Some countries have already made the decision to legalize aid in dying: the Netherlands, Belgium, Switzerland, and Luxembourg. Five U.S. states, Montana, Oregon, Washington, Vermont, and California have approved similar laws, and other states are considering such legislation. Pro-life organizations and most conservative churches have taken positions against any form of aid-assisted dying. The U.S. Conference of Catholic Bishops in a position paper called To Live Each Day with Dignity, states: “As Christians we believe that even suffering itself need not be meaningless (!), for as Pope John Paul II showed during his final illness, suffering accepted in love can bring us closer to the mystery of Christ’s sacrifice for the salvation of others.” Can pain and suffering be a soul-saving lesson?

I have had doctors ask me where the pain I’m suffering from a bad hip joint is on a scale of 1 to 10. I don’t have a clue whether it’s a 3 or 9. I have suffered from broken teeth and bones, from being beaned by baseballs, from being blocked by huge offensive tackles, from snagging fishhooks caused by errant casts, but never from hourly, daily, weekly, monthly, ever-present chronic pain. I have the atheistic opinion that religious authorities who preach that severe pain and suffering can be a soul-serving lesson have never experienced that kind of pain. We cannot cure every disease and we cannot treat or alleviate every pain. Often we cannot kill the pain and suffering without killing the patient. California Governor Jerry Brown, a Catholic, recently signed a bill authorizing aid in dying. In a way, he used Hamlet’s soliloquy to state his reasons for his approval of the legislation: “In the end, I was left to reflect on what I would want in the face of my own death. I don’t know what I would do if I were dying in prolonged and excruciating pain. I am certain, however, that it would be a comfort to be able to consider the options afforded by this bill.”

Shakespeare: “And Then The Lover, Sighing Like A Furnace, With A Woeful Ballad Made To His Mistress’ Eyebrow”

I have not read all of The Joy of Love’s 256 pages, but I have read the New York Times article The End of Catholic Guilt by Timothy Egan who summarizes the contents with both humor and specificity. Egan concludes that Pope Francis implies that “there’s considerable fun to be had in human relationships.” The pope seems to approve of sex by using such shocking terms as “erotic dimension” and the “stirring of desire!” (Egan calls the pope’s use of the word “erotic” as “blush-worthy” for a man who has taken a vow of chastity.) Egan covers the attitudes of previous popes in a couple of devastating paragraphs: “Sex was dirty. Sex was shameful. Sex was unnatural. Thinking about it was wrong. …Sex had one purpose: procreation, the joyless act of breeding….I can’t tell you how many Catholics I know who are trying to work through the consequences of those sexual strictures. They wonder if there are still people doing time in purgatory because of the misdemeanor sins of masturbation or premarital sex. Life was all don’ts and dark thoughts.”

I have a feeling that Pope Francis and Shakespeare would have similar views about the power of love and sex. Shakespeare’s plays are loaded with eroticism, desire, ecstasy, and ballads made to eyebrows. Here are just a few samples:

From A Midsummer Night’s Dream:

“The course of true love never did run smooth.”

“Lovers and madmen have such seething brains, such shaping fantasies, that apprehend more than cool reason ever comprehends.”

From As You Like It: “Love is merely a madness, and, I tell you, deserves as well a dark house and a whip as madmen do.”

From Hamlet: “This is the very ecstasy of love, who violent property fordoes itself and leads the will to desperate undertaking.”

From Romeo and Juliet: “Love is a smoke raised with the fume of sighs.”

“Is love a tender thing? It is too rough, too rude, too boisterous, and pricks like thorn.”

From Two Gentlemen of Verona: “Love is like a child that longs for everything that he can come by.”

In the Joy of Love Pope Francis writes: “Sex is a marvelous gift from God. The stirring of desire or repugnance is neither sinful nor blameworthy….Hence it can no longer be said that all those in any ‘irregular’ situations (“irregular” is a rather tantalizing word to be used here!) are living in a state of mortal sin.” Egan writes: “The old message was: If you break the rules, you’re condemned. Shame, shame, shame. The new message is: Welcome, for forgiveness is at the heart of this faith.”

“The Rusted Plumbing of Church Doctrine”

Egan ends his article with a great metaphor: “Pope Francis is merely acknowledging the obvious. As he’s done before, he’s using words to change hearts, rather than trying to wrangle with the rusted plumbing of church doctrine.” Many Catholics, particularly those in Europe and the United States, have already substituted new plastic pipes for the rusted pipes of Vatican doctrine. There are thousands of couples of “irregular” unions (whatever they are!) who have stopped following the church’s dictates about many aspects of sex. Recent studies on the use of contraceptives by Catholic couples indicate that only one in ten regular attendees at Mass feel any guilt about using a number of pills and devices.

In his play As You Like It Shakespeare describes seven stages of men and women in his 16th Century world. His summary is still as important today as it was 400 years ago:

All the world’s a stage and all the men and women merely players. They have their exits and their entrances. And one man in his time plays many parts, his acts being seven ages.

At first the infant, mewling and puking in the nurse’s arms.

And then the whining school boy, with his satchel and shining morning face, creeping like snail unwillingly to school.

And then the lover sighing like a furnace, with a woeful ballad to his mistress’ eyebrow.

Then the soldier full of strange oaths and bearded like the pard, jealous in honor, sudden and quick in quarrel, seeking the bubble reputation in the cannon’s mouth.

And then the justice in fair round belly with good capon lined, with eyes severe and beard of formal cut, full of wise saws and modern instances, and so he plays his part.

The sixth age shifts into the lean and slipper’d pantaloon, with spectacles on nose and pouch on side, for his shrunk shank, and his big manly voice turning again toward childish treble, pipes and whistles in his sound.

Last scene of all, that ends this strange eventful history, is second childishness and mere oblivion, sans (without) teeth, sans eyes, sans taste, sans everything.

Hopefully, I’m still between the sixth and seventh ages in “this strange eventful history.”