Wild Geese

A chorus of sharp honking sent shivers up my spine. Looking up over the nested rows of suburban homes, I scanned the low, gray sky until the V of geese came into view. Their wild calling seemed out of place in my brother’s orderly, central Iowa neighborhood, and my brain flashed back to a crisp September day in the Boundary Waters of northern Minnesota.

Three canoes floated among yellowing lily pads and tree reflections in a cozy bay, while the fourth canoe landed and began unloading for the portage. My dad was the first to hear the geese, as usual. He’s always been tuned in to their music. We all shifted expectantly toward the sound, gently sculling paddles and maneuvering boats to ease the strain on our necks, but saw only the dense spires of spruces and blue sky.

A few moments passed before the flock’s vanguard came into view, and they pulled their followers forward until the long ends of the V trailed over our heads. Taking stock of the early afternoon sun over my left shoulder, I noted with satisfaction that the geese were heading south. The urgency we imagined in their voices felt appropriate after our trip of windy days and chilly nights. We, too, would soon head south to wait out the winter with warm beds and plentiful food.

Our romantic notions of migrating flocks Canada geese as the forerunners to fall and the harbingers of spring are not as accurate as they once were, though. In the 1940s, most geese were migratory, and Aldo Leopold wrote eloquently in A Sand County Almanac about “the geese that proclaim the seasons on our farm…” “One swallow does not make a summer,” he declared, “but one skein of geese, cleaving the murk of a March thaw, is the spring.”

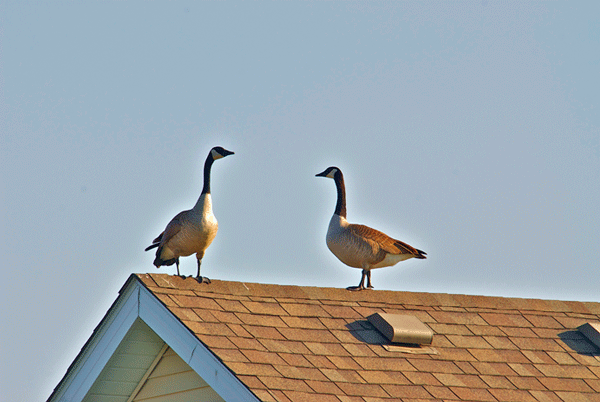

So what was this skein of geese doing—flying north, no less—in February, in a subdivision, less than 150 miles south of the latitude of Leopold’s shack?

As humans have changed the landscape and the climate, some of the 11 subspecies of Canada geese have changed their patterns to match. Many geese who breed in the far north do still migrate long distances. Other northern populations migrate, but don’t travel as far south. The southernmost breeding populations don’t participate in winter migration at all. This shift may be due to newer farming practices that leave more waste grain (a favorite food of geese) in the fields, more year-round open water near dams or industries, and a decrease in snow cover on the tasty grass of our lawns, golf courses, and parks. My guess is that the honking flock over suburbia was headed north to the Saylorville reservoir, or to the windswept farm fields disappearing under the creep of development.

Living near people has proven to be beneficial to the resident geese, since cities provide tender green lawns with a wide-open view, a reduction in predators (including human hunters), and occasional supplemental feeding. Migrating geese must contend with the treachery of travel, predation, storms, and hunting. Their numbers seem to be held in check, while the resident geese are an increasing nuisance and hazard.

Goose poop bringing coliform bacteria to swimming beaches and drinking water, and crop damage are two complaints, but it gets more serious than that. Some resident goose populations crowd out other migratory waterfowl in the wildlife refuges that were created to support them. In 2012, there were 240 goose-airplane collisions, and in 2009 a flock of geese took out both engines on a US Airways plane and forced the pilot to make an emergency landing on the Hudson River.

What’s fascinating, though, is that almost all geese—migratory or not—make short journeys north in late summer after breeding to munch on plants in an earlier state of growth. The younger plants contain additional nutrients needed to fuel the geese’s molt and feather re-growth.

Migratory vs resident. Wild harbinger of seasons vs common nuisance. Even with Canada geese, nothing is just black or white.

For over 45 years, the Cable Natural History Museum has served to connect you to the Northwoods. Come visit us in Cable, WI! Our new exhibit: “Lake Alive!” opened May 1, 2015, and will remain open until March 2016.

Find us on the web at www.cablemuseum.org to learn more about our exhibits and programs. Discover us on Facebook, or at our blogspot, http://cablemuseumnaturalconnections.blogspot.com.