Yucca Mountain Scientifically Unsuitable for Rad Waste Repository

The Nuclear Waste Policy Act (NWPA) sets strict standards that must be met before a high-level radioactive waste repository can be licensed. The licensing process for the Yucca Mountain dump site, which has cost $9 billion to date, was halted in 2010 because the site can no longer be defended on scientific grounds. In its current location, 90 miles from Las Vegas, the dump would also be unlawful because according to the 1863 Treaty of Ruby Valley, the Western Shoshone Nation holds title to Yucca Mountain and the Western Shoshone overwhelmingly oppose the dump.

While Congressional leaders talk today about reconsidering Yucca, crucial scientific findings (some listed below) should permanently disqualify it. Principle among them is that the geology of Yucca Mt. doesn’t meet the original statutory requirements established by the NWPA. Even after hydrological, geological, volcanic and seismological show-stoppers have been revealed, the licensing process was not halted (until 2010). Instead, NWPA specifications have been repeatedly weakened, leading one Nevada Governor, Kenny Guinn, to accuse the Energy Dept. of lowering standards to win approval for the site.

In 2014, Allison Macfarlane, a former chair of the US Nuclear Regulatory Commission (NRC), warned that when the licensing process was halted, there were still hundreds of “contentions” challenging the application. The General Accounting Office reported that the project’s former managing contractor, Bechtel SAIC, had in 2001 identified 293 unresolved technical issues to further analyze before licensing could proceed. Each contention must be argued before a panel of administrative law judges. Macfarlane wrote in Science magazine that the “[Dept. of Energy] will not be able to submit an acceptable application to NRC within the express statutory time frames for several years because it will take that long to resolve many technical issues.” Macfarlane concluded that “disposal of high-level nuclear waste at Yucca Mountain is based on an unsound engineering strategy and poor use of present understanding of the properties of spent nuclear fuel.”

In 2007, the Bow Ridge earthquake fault was discovered by the US Geological Survey’s Yucca Mt. Project Branch to be hundreds of feet east of where it had estimated. It passes directly under a planned pad where waste canisters would be kept for years before they are entombed in tunnels inside the mountain, according to the USGS’s May 21, 2007 letter. The error means designers must revamp or scrap their plans. Yucca Mt. project officials said they are still developing repository design, construction and operating ideas. The DOE has never produced blueprints that Nevada state officials can review and critique.

In 2004, the US Circuit Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia ruled that the National Academy of Sciences found “no scientific basis for limiting the time period of the individual risk standard to 10,000 years…” The Academy reported instead that “repository performance” must be judged on “a time scale that is on the order of [one million] years at Yucca Mountain.” It’s been known for decades that some of the waste, as a New York Times science writer said, “remains radioactive for millions of years,” that it “would be hazardous for millions of years,” and, as the St. Paul Pioneer Press reported, that “nearly 100 million pounds” of high-level waste “will remain lethal for millions of years.” The National Academy of Sciences found in 1983 that the “chemical characteristics of the water at Yucca Mt. are such that the wastes would dissolve more easily than at most other places.” The NAS also “make[s] the assumption that a nuclear waste repository will eventually leak,” and “The wastes would … most likely reach humans through water flowing underground through the wastes and eventually reaching the surface through springs or wells.”

In 2002, a mild earthquake on June 14, about 12 miles southeast of Yucca Mt. fueled opposition to plans for the dump. The magnitude-4.4 quake was called a “wake-up call” by critics who pointed to the potential for damage to above-ground storage facilities, where thousands of tons of waste brought to the site would be kept for decades while it cools. “If anyone ever wondered about the wisdom of locating an underground radioactive dump site on an active fault line, this shows why,” Rep. Shelley Berkley, D-Nev., said after the quake.

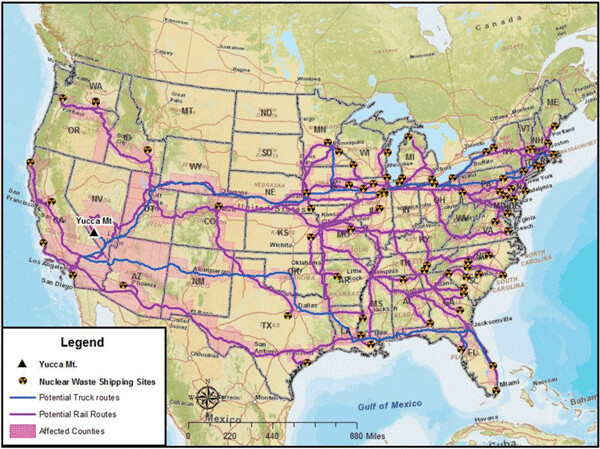

In 1999, a DOE report declared that leaving the waste in storage at reactor sites is just as safe as moving it to Yucca Mt. -- as long as the waste is repackaged every 100 years. Given the uncertainties about Yucca Mt. and the risks of moving waste fuel, it makes sense to leave the material were it is generated at the reactor sites while developing alternatives. Independent scientists suggest on-site, above-ground, monitored storage, hardened against terrorism, along with additional measures for safety and security.

In 1998, evidence that the inside of the mountain is periodically flooded with water came in the form of zircon crystals found deep inside. “Crystals do not form without complete immersion in water,” said Jerry Szymanski, formerly the DOE’s top geologist at Yucca. Szymanski’s finding that deep water rises and falls inside Yucca Mt. means “hot underground water has invaded the mountain and might again in the time when radioactive waste would still be extremely dangerous. The results would be catastrophic.” In 1998, the Yucca Mt. site was found to be subject to earthquakes or lava flows every 1,000 years -- 10 times more frequently than earlier estimated -- according to a California Institute of Technology study. The finding meant that radiation dispersal from the site is much more likely during the dump’s radioactive hazard period.

In 1997, DOE researchers announced that rain water had seeped down 800 feet from the top of Yucca Mt. into the repository in a mere 40 years (as dated by chlorine-36). Government scientists had earlier claimed that rainwater would take hundreds or thousands of years to reach the waste caverns. Federal officials have long required that the existence of fast-flowing water would disqualify the site.

In 1995, government physicists at Los Alamos National Laboratory warned in an internal report that the wastes might erupt in a nuclear explosion and scatter radioactivity to the winds or into groundwater, or both. Dr. Charles D. Bowman and Dr. Francesco Venneri found that staggering dangers will arise thousands of years from now -- after steel waste containers dissolve and plutonium begins to disperse into surrounding rock. Dr. John Browne, head of energy research at Los Alamos National Lab, said about the research paper, “Our feeling is that the subject is so important that it deserves additional peer review outside the laboratory.” The DOE’s former top geologist Jerry Szymanski said to the Washington Post, “You’re talking about an unimaginable catastrophe. Chernobyl would be small potatoes.”

In 1990, the National Research Council said in a study that the DOE’s Yucca Mt. plan is “bound to fail” because: a) requiring predictions of safety for even 10,000 years is a scientific impossibility; and b) the Nuclear Waste Policy Act demands a level of safety that science cannot guarantee. The US Circuit Court of Appeals later ordered the government to judge dumpsite performance based not on a 10,000-year, but a one-million-year time scale.

In 1989, sixteen scientists from the US Geologic Survey charged that the DOE was using stop-work orders “to prevent the discovery of problems that would doom the repository.” The geologists reported that, “There is no facility for trial and error, for genuine research, for innovation, or for creativity.” Even the NRC complained that, “work at Yucca Mt. seemed designed mostly to get the repository built rather than to determine if the site is suitable.”

If Yucca Mt.’s containment puzzles can be solved or ignored and it is rehabilitated and licensed after sitting unattended for seven years, gamblers in Las Vegas and scores of other cities around the country will have a problem of health science to face. Fred Dilger, a Clark County, Nevada planner and former state transportation analyst, has warned that when waste trains go through town, “All of the casinos on the west side of Las Vegas Boulevard would be bathed in gamma radiation.”